How South Korea’s gas ambitions sustain the occupation of Gaza

By Hwanbin Jeong | MEMO | January 27, 2026

“Eni participated in a legally announced international tender for offshore exploration licences in waters located within Israel’s Exclusive Economic Zone bordering Egypt … Eni does not foresee being involved in activities in the area in the future.”

“Eni participated in a legally announced international tender for offshore exploration licences in waters located within Israel’s Exclusive Economic Zone bordering Egypt … Eni does not foresee being involved in activities in the area in the future.”

This is how Eni, a major Italian energy company, responded to a question from Italy’s national public broadcaster Radiotelevisione italiana (RAI) regarding its alleged involvement in “disputed waters off the coast of Gaza.”

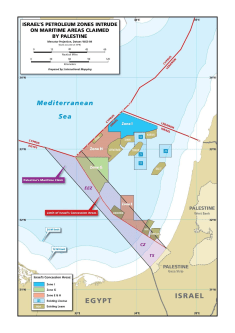

In December 2022, Israel launched its fourth offshore gas exploration licencing round. The Israeli Ministry of Energy described the tender areas as “part of the Exclusive Economic Zone of the State of Israel”, while also acknowledging them as “not yet fully delimited”; some portions overlap with Gaza’s maritime boundaries.

ENI participated in the tender as the operator of a consortium, which won the bid for Zone G on 29 October, 2023. According to Adalah, an Israeli legal centre for Arab minority rights, 62.2 per cent of Zone G lies within maritime areas claimed by Palestine as part of its Exclusive Economic Zone, covering 1,063.3 square kilometres.

Since then, civil society groups have mounted sustained pressure on ENI to withdraw from cooperation with an illegal occupation. After more than two years of campaigning, ENI informed RAI on 2 December, 2025 that it would disengage from the area. Yet the struggle did not end there. The consortium includes two other companies: Israel’s Ratio Petroleum and Dana Petroleum, which was acquired through a hostile takeover in 2010 by the Korea National Oil Corporation (KNOC), a South Korean state-owned enterprise.

Recently, South Korean civil society groups have pressed KNOC to clarify its position and withdraw from the project. On 18 December, 2025, KNOC replied that, “after the end of the Israel–Palestine war, and following monitoring of the international situation, the company will review whether to proceed with exploration together with consortium partners such as ENI.” This reveals an intention to carry the project forward once international scrutiny fades, thereby reducing legal and political risk.

How pillage sustains occupation

Pillaging natural resources is a common problem many Global South states still struggle with, but Palestine’s case is uniquely profound for its political consequences. When RAI presented the issue alongside ENI’s position on 14 December, it highlighted Italy’s refusal to recognise Palestinian statehood and underscored a structural reality: “management of these resources risks consolidating the occupation rather than bringing it to an end.”

KNOC’s involvement raises a qualitatively different level of concern. KNOC’s role as a state-owned public enterprise places the issue squarely within the realm of state responsibility under international law. Thus, South Korea has a much stronger incentive to favour the continued occupation of Gaza.

South Korea presents its position on Israel–Palestine as politically neutral. In practice, however, it refers to Palestine only as “self-government”, while pursuing close cooperation with Israel in economic and defence sectors, including arms sales; it became the first Asian country to conclude a bilateral free trade agreement with Israel in 2022. South Korea has also refrained from criticising Israel’s violations of international law. In fact, it has been more muted than many Western countries and even Japan.

Consider what South Korea’s position could mean at this critical juncture in Gaza. The two years of Israeli genocide and devastating destruction have utterly deprived Gazans of any political capability. On 14 January, the USA announced moving to phase two of the Gaza ceasefire, under which Palestinian self-determination is practically nullified, with no defined timeline. Only technocratic participation is allowed, subject to the supervision of an international administering body referred to as a “Board of Peace”, chaired by US President Donald Trump.

Under this arrangement, the Board would make decisions over Gaza’s offshore gas resources, rather than the Palestinian government in the West Bank. South Korea would support this marginalisation of Palestinian self-determination for the sake of safer gas exploitation.

Decolonisation as leverage

The urgency of preventing South Korea from participating in the pillaging of Palestinian resources is clear. The problem is how. Advocacy for Palestinians within South Korea remains weak in both numbers and political influence. Public sympathy is also limited. According to a survey conducted by Korea Research in September 2025, only 39 per cent of respondents reported feeling a great deal of pity for Palestinians, compared with 19 per cent for Israelis. A plurality of respondents (41 per cent) held both sides equally responsible for the war.

It is therefore significant that the United Nations General Assembly has recently revitalised and institutionalised the concept of “colonialism in all its forms and manifestations”. This expanded framework aims to address various aspects of oppression including the illicit appropriation of natural resources. On 14 December, 2025, the UN marked the first International Day against Colonialism in All Its Forms and Manifestations. Four days later, at a high-level plenary meeting commemorating the occasion, UN Secretary-General António Guterres declared:

“Eighty years ago, the United Nations was created to save succeeding generations from war, to uphold human rights and to advance progress in larger freedom. Today, on this first International Day against Colonialism, let us renew that promise – not only by ending colonialism in its traditional forms, but by dismantling its remnants wherever they endure.”

This new phase of decolonisation did not become relevant to Palestine by coincidence. In 2024, Palestine was among the sponsoring states of General Assembly resolution A/RES/79/115, which introduced “the eradication of colonialism in all its forms and manifestations” as a formal agenda item for the 80th session of the General Assembly. Building on this, in 2025, resolution A/RES/80/106 designated 14 December as the International Day against Colonialism and placed the eradication of colonialism in all its forms and manifestations on the General Assembly’s agenda on an annual basis. With 116 votes in favour, the resolution marked the institutionalisation of an expanded decolonisation framework.

Palestine’s engagement with this framework is not primarily driven by the protection of gas resources. At stake is whether its supposedly temporary condition of occupation is recognised as a matter of decolonisation. This position has found broad resonance across the Global South. At the 18 December plenary meeting, 12 of the 33 states that took the floor explicitly referenced Palestine while advocating an expanded understanding of decolonisation. A further 10 states endorsed such positions through statements delivered by their group representatives—Venezuela for the Group of Friends in Defence of the Charter of the United Nations and Uganda for the Non-Aligned Movement. Palestine, in other words, lay at the centre of the debate.

Nearly five months have passed since the opening of the General Assembly’s 80th session with its new agenda item on the eradication of colonialism in all its forms and manifestations. Aside from resolution A/RES/80/106, however, no substantive resolutions have yet been adopted or debated under this item. Palestine is unlikely to advance the issue of gas exploitation on its own, given the risk of jeopardising relations with the South Korean government. Any meaningful challenge will therefore require a broader coalition of states with similar interests. The question is who has the courage to initiate it.

No comments yet.

Leave a comment