Bad Science, Big Consequences

How the influential 2006 Stern Review conjured up escalating future disaster losses

By Roger Pielke Jr. | The Honest Broker | February 2, 2026

For those who haven’t observed climate debates over the long term, today it might be hard to imagine the incredible influence of the 2006 Stern Review on The Economics of Climate.1

The Stern Review was far more than just another nerdy report of climate economics. It was a keystone document that reshaped how climate change was framed in policy, media, and advocacy, with reverberations still echoing today.

The Review was commissioned in 2005 by the UK Treasury under Chancellor Gordon Brown and published in 2006, with the aim of assessing climate change through the lens of economic risk and cost–benefit analysis. The review was led by Sir Nicholas Stern, then Head of the UK Government Economic Service and a former Chief Economist of the World Bank, from the outset giving the effort unusual stature for a policy report.

As the climate issue gained momentum in the 2000s, the Review’s conclusions that climate change was a looming emergency and that virtually any cost was worth bearing in response were widely treated as authoritative. The Review shaped climate discourse far beyond the United Kingdom and well beyond the confines of economics.

One key aspect of the Stern Review overlaps significantly with my expertise — The economic impacts of extreme weather. In fact, that overlap has a very surprising connection which I’ll detail below, and explains why back in 2006 I was able to identify the report’s fatal flaws on the economics of extreme weather in real time, and publish my arguments in the peer-reviewed literature soon thereafter.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

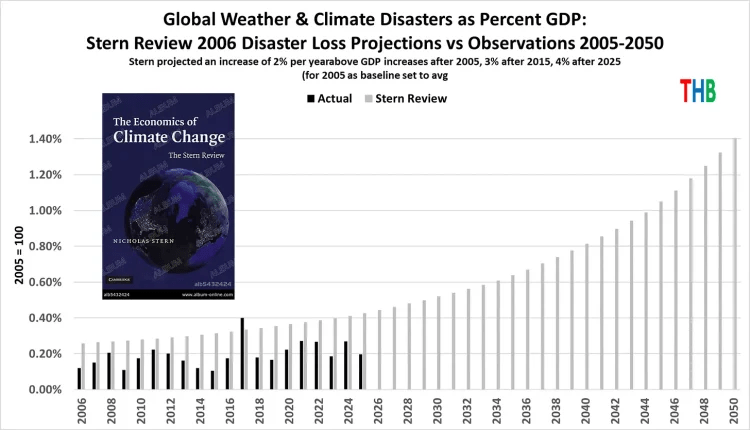

I have just updated through 2025 the figure below that compares the Stern Review’s prediction of post-2005 increases in disaster losses as a percentage of global GDP with what has actually transpired.

Specifically, the figure shows in light grey the Stern Review’s prediction for increasing global disaster losses, as a percentage of GDP, from 2006 through 2050.2 These values in grey represent annual average losses, meaning that over time for the prediction to verify, about half of annual losses would lie above the grey bars and about half below.

The black bars in the figure show what has actually occurred (with details provided in this post last week). You don’t need fancy statistics to see that the real world has consistently undershot the Stern Review’s predictions over the past two decades.

The Stern Review forecast rapidly escalating losses to 2050, when losses were projected to be about $1.7 trillion in 2025 dollars. The Review’s prediction for 2025 was more than $500 billion in losses (average annual). In actuality losses totaled about $200 billion in 2025.

The forecast miss is not subtle.

How did the Stern Review get things so wrong?

The answer is also not subtle and can be summarized in two words: Bad science.

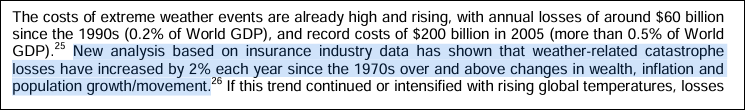

Let’s take a look at the details. The screenshot below comes from Chapter 5 of the Review and explains its source for developing its prediction, cited to footnote 26.

As fate would have it, footnote 26 goes to a white paper that I commissioned for a workshop that I co-organized with Munich Re in 2006 on disasters and climate change.

That white paper — by Muir-Wood et al. — is the same paper that soon after was played the starring role in a fraudulent graph inserted into the 2007 IPCC report (yes, fraudulent). You can listen to me recounting that incredible story, with rare archival audio.

But I digress . . . back to The Stern Review, which argued:

If temperatures continued to rise over the second half of the century, costs could reach several percent of GDP each year, particularly because the damages increase disproportionately at higher temperatures . . .

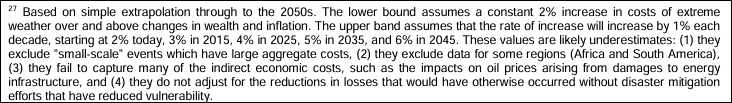

The report presented its prediction methodology in the footnote 27, shown in full below, which says: “These values are likely underestimates.”

Where do these escalating numbers come from? Who knows.

They appear to be just made up out of thin air. The predictive numbers do not come from Muir-Wood et al., who do not engage in any form of projection.

The 2% starting point for increasing losses — asserted in the blue highlighted passage in the image above — also does not appear in Muir-Wood et al. which in fact says:

When analyzed over the full survey period (1950 – 2005) the year is not statistically significant for global normalized losses. . . For the more complete 1970-2005 survey period, the year is significant with a positive coefficient for (i.e. increase in) global losses at 1% . . .

The Stern Review seems to have turned 1% into 2% and failed to acknowledge that over the longer-period 1950 to 2005, there was no increasing trend in losses as a proportion of GDP. The escalating increase in annual losses from 2% to 3%, 4%, 5%, 6% every decade is not supported in any way in the Stern Review, nor is it referenced to any source.

When the Stern Review first came out, I noticed this curiosity right away, and did what I thought we scholars were expected to do when encountering bad science with big implications — I wrote a paper for peer review.

My paper was published in 2007 and clearly explained the Muir-Wood et al. and other significant and seemingly undeniable errors in the Stern Review.

Pielke Jr, R. (2007). Mistreatment of the economic impacts of extreme events in the Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change. Global Environmental Change, 17(3-4), 302-310.

I explained in that paper:

This brief critique of a small part of the Stern Review finds that the report has dramatically misrepresented literature and understandings on the relationship of projected climate changes and future losses from extreme events in developed countries, and indeed globally. In one case this appears to be the result of the misrepresentation of a single study. This cherry picking damages the credibility of the Stern Review because it not only ignores other relevant literature with different conclusions, but it misrepresents the very study that it has used to buttress its conclusions.

Over my career in research, I’ve had some hits and some misses, but I’m happy to report that I got this one right at the time and it has held up ever since. Of course, perhaps a more significant outcome of this episode, and a key part of my own education in climate science, is that my paper was resoundingly ignored.

One reason that science works is that scientists share a commitment to correct errors when they are found in research, bringing forward reliable knowledge and leaving behind that which doesn’t stand the test of time.

I learned decades ago that in areas where I published, self-correction was often slow to work, if not just broken. Over the decades that pathological characteristic of key areas of climate science has not much improved (e.g., see this egregious example).

The Stern Review helped to launch climate change into top levels of policy making around the world. Further, we can draw a straight line from the Review to the emergence of (often scientifically questionable) “climate risk” in global finance a decade later. It still rests on a foundation of bad science.

1 My ongoing THB series on insurance and “climate risk” in finance prompted me to revisit the 2006 Stern Review, hence this post.

2 Note that the Review explicitly referenced the tabulation of global economic losses from extreme weather events as tabulation by Munich Re, which is the same dataset that I often use, such as in last week’s THB post on global disaster losses. The comparison here is thus apples to apples.

No comments yet.

Leave a comment