What the NML vs Argentina case means for the world

By Oscar Ugarteche | ALAI | July 29, 2014

At the end of June, 2014, a New York Second District Judge ruled in favour of a hedge fund, NML Capital, and against the Republic of Argentina. The issue at stake was if a hedge fund that bought debt paper three years after a debt restructuring, had or not the right to collect on the same terms as the rest of creditors. The ruling was, yes it has. The problem is that in the original debt restructuring creditors received new instruments with a strong haircut that made the payback possible for Argentina, while the old instruments do not have any debt reduction. In this way, the profitability of the hedge funds in buying, in 2008, those old unwanted instruments of a debt rescheduled in 2005, and unpaid since 2001, will be of 1,600%. The way the hedge fund works is through buying, at a very heavy discount, the debt paper that was not included in the rescheduling, and then suing the Argentine Government for full payment of capital plus all the interest due. Interest comes free when debt paper is under impaired value credit category. Elliott Associates, major shareholder of NML Ltd., has made a reputation for cornering Governments in times of need and getting away with it. Panama was the first one, Congo, Peru, Argentina amongst others. Their argument is that these lawsuits discipline the debtors.

The international relevance of this sort of activity is that it brings to the fore the nature and presence of US law and rulings in international finance. Most US dollar-denominated debt is issued under US law and subject to the Southern district courts of New York City, those near Wall Street. This means that if Botswana borrows from Uganda in US dollars, it is almost certain those contracts will be written under NY law. The ramifications of this are that any legal action between those two countries will be subject to New York law, with the implication that New York law becomes world law and is applied worldwide, becoming a mechanism of coercion. The enforcement of payment in the ruling is executed through bank account or asset embargoes. For example, in 2012 the Argentine frigate Libertad was seized in a port in Ghana under orders from the New York judge. She was released after some months under a ruling from the UN International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea because she holds diplomatic immunity.

The last ruling includes non-dollar denominated instruments signed under British and other laws, with the argument that the payment due to one creditor is equally due to all. Ecuador, a debtor that defaulted and bought its debt at a 70% discount in 2008 decided in May 2014 to buy back 80% of the held out debt plus interest and got it over with.[1] The huge return on investment for unpaid bondholders was less of a problem for Ecuador than the likelihood of having its accounts frozen after the new loans were disbursed, given it is a dollar denominated economy.[2]

Vulture Funds

Vulture funds are hedge funds specialised in buying debt paper from problem debtors who have solved or are in the process of solving a default problem. They jump over their prey, the struggling country, purchase his debt instruments not included in the final debt restructuring arrangement at a small percentage of face value and sue the country for full payment including interest. If the country is undergoing duress, the fund is perfectly happy to subject her citizen’s to more hardship in exchange for a huge profit. This is possible because debt papers before 2001 did not have collective action clauses (CAC) yet, which means that if most creditors agreed to a debt workout solution, this included only those who joined voluntarily. With a CAC, if a large portion of the creditors are in favour of a workout, all instruments are included.

The lack of CAC was made evident when Elliott sued Peru[3] in the 1990s and won the case in 2000. Peru had undergone the longest sovereign default in history, from 1984 to 1994, and came out with a debt restructuring that included a sharp haircut and new Brady bonds. Only four instruments were left at Swiss Bank Corp., the Peruvian manager of the Brady deal, belonging to Banco Popular, a bankrupt bank closed in 1992. These four instruments were sold by Swiss Bank, the agent for Peru’s debt, to Elliott not to Peru, after the Brady deal had been signed in what appeared to be a breach of contract on Swiss bank’s side. Elliott then sued Peru and apparently got a helping hand from a Peruvian lawyer who happened to be an official at the Ministry of Finance in 1994. There was much information passed in 1994 from the Ministry of Finance to the creditors leading to the trial of Finance Minister Camet, responsible for this operation. He died in 2013 serving prison term at home for this and other cases.

Elliott sued Peru for 100% of capital. It had paid 5% of the face price of the papers. On top it sued it for unpaid interest since 1984. The profitability on the Peruvian operation was 1,600%. Peru’s case was made using the Champerty Doctrine that says that no debt purchased with the sole purpose of harming a debtor should be taken into account by the US judiciary. Investors who become creditors through the purchase of debt instruments at a time when the debtor is undergoing hardship should not be taken into legal consideration. Nevertheless, the New York judge ruled against Peru. Amongst the group of investors was a former US ambassador to Peru. It remains unclear if the former ambassador was there on his own right or as a representative of the US State Department. The Peruvian Government lost the case and the appeal and as a result all Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) dollar transactions were blocked. After that, Elliott sued Peru in the Belgian courts that ruled in favour of Elliott and prevented the use of Brussels based Euroclear.[4] It then proceeded to use Clearstream in Luxembourg, but knowing this would also be blocked. The argument of the Belgian Court was pari passu, all creditors should be treated equally.

The Argentine operation[5]

NML associates, a subsidiary used by Elliott to do the Argentine operation, purchased 50 million dollars of debt paper that had not entered the restructuring scheme in 2005 and has sued for 1,500 million USD. The holders of those unrestructured papers sold them to NML in 2008 after the 2005 swap was arranged and before the 2010 swap was finalised. They then started the legal proceedings that have lasted six years until finally the judiciary ruled in favour of NML. The Argentine debt is held with creditors in many jurisdictions and not all are subject to US law, theoretically. Equally there are dollar and non-dollar denominated instruments and agent banks operating outside the US. The ruling however starts from a peculiar reading of the principle of pari passu, equal payments must be made to all creditors either if they restructured or if they did not, regardless of the law applied in their contract. The Trustee in charge of making the payments is Bank of New York who must abide by this ruling and comply with the law.

This ruling essentially takes away the incentive to restructure sovereign debts normally done on the basis of debt reductions. Worse, it places legal creditors who underwent the restructuring procedure on the same basis as highly speculative investors who operate on bad faith buying the debt after the swaps are finalised, in the spirit of Champerty. The gravest consequence is that a New York ruling is converted into a global ruling for any Argentine assets held by anyone anywhere. An explanation was given that the ruling is not meant to be a precedent[6] which means the ruling was done as a specific punishment reminding the ruling of the Court of the Hague against Austria in 1931 when it decided it wanted to form a customs union with Germany. Then as now, if it is not a precedent, it is a punishment. The question is why.

Ways forward

Argentina’s position is that it is the right of a sovereign debtor to restructure its debt. It believes in the principle of non-intervention in foreign states and does not admit legal actions executed outside the natural range of the justice of the United States. In so doing it believes it is defending the property rights of the holders of Argentine bonds, especially those whose right is not governed by justice of the United States. But also of those who entered willingly and in good faith in the swap agreements of 2005 and 2010 and who this ruling has declared, for all purposes, invalid. Argentina is opening the fight by depositing the money at the Bank of New York so bondholders will collect. As the money belongs to the bondholders, they should be able to do so. This is the sense of a communique published in the international press in July, 2014, a week after the ruling was made public.

The vultures, being what they are, have a press campaign stating that Argentina does not want to pay any of its debt nor comply with US law. Argentina, on its side, has informed the clients it will pay through Euroclear which should protect them from the US international payment embargo, as book entry accounts in Euroclear enjoy unconditional immunity from attachment.

Finally

The international support given to Argentina is an expression of what is globally perceived as being an unjust ruling from a court that should not have extraterritorial functions over currencies and assets that are not US assets. The capture of a payment for Cuban cigars traded between Germany and Denmark under US law is an expression of the extraterritorial use of US law, which is unacceptable.[7] If the international system is going to evolve it must go in the direction of international law and international courts and not in the direction of local law with a local court with global ramifications. This implies a new financial architecture which, following the lines of the BRICS in terms of financial reforms, could mean the creation of a clearing house and greater use of non-dollar means of payments in international transactions. The creation of an international financial law process in the United Nations sphere, similar to that being developed for international trade law (UNCITRAL), is vital. This should come together with the development of the concept of international tribunals for debt arbitration in order to obtain reasonable debt workouts of sovereign defaults following the principles of fair and transparent arbitration that should begin with a debt audit, keeping the Champerty principle in mind.

There are major flaws in the international financial architecture that allow the supreme court of the leading debtor country in the world to rule over the lives of millions of people in another land in an unjust, unfair and non-transparent manner. The ruling affects the position of other bondholders in non-dollar denominated instruments issued under other legal domains and opens the possibility of embargoes worldwide. It also opens up the possibility of disavowing the debt to international bondholders, following the same logic in reverse.

The practice of extorting money from troubled nations in favour of a minuscule group of investors who purchase debt paper after debt negotiations with the rightful creditors are finished, with the sole purpose of extorting an unfair profit from it, is sanctioned by US law. This is called the Champerty Doctrine. This sort of practice was outlawed in New York by Judiciary Law §489 http://codes.lp.findlaw.com/nycode/JUD/15/489#sthash.TroVCUs0.dpuf. The rulings from the New York courts, however, seem to favour the vultures and the application of the rulings worldwide has dire consequences on the debtor.

The lesson from the NML-Argentina case is that non-OECD countries in the future should not issue debt instruments in US dollars nor be subject to New York law and courts, given the risk expressed above. Given the world power structure change, BRICS should continue to develop a new international financial architecture. International trade should equally not be settled in US dollars and a new non-OECD international clearing house should be started to prevent harassments from dubious US rulings. International capital is not going to give up its power to extort wealth from distressed countries.

Newcastle and Fortaleza, 15 July, 2014.

– Oscar Ugarteche, Peruvian economist, is the Coordinador del Observatorio Económico de América Latina (OBELA), Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas de la UNAM, México – http://www.obela.org. Member of SNI/Conacyt and president of ALAI http://www.alainet.org

[1] “Ecuador Sells $2 Billion in to Bond Market,” Bloomberg, 17 June, 2014, at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-06-17/ecuador-plans-bond-market-return-today-five-years-after-default.html

[2] “Argentina’s Woes don’t Chill Ecuador’s New York Bond Sales”, Bloomberg, June 24, 2014 at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-06-24/argentina-s-chilling-effect-on-new-york-debunked-by-ecuador-sale.html

[3] Congreso del Perú. Comisión Investigadora de la Corrupción. Caso Elliott. Junio, 2003. Fallo judicial. http://www.congreso.gob.pe/historico/ciccor/anexos/CASO%20ELLIOT%20ASSOCIATES%20LLP%20TOMO%20II.pdf

[4] Rodrigo Olivares-Caminal, “The Pari Passu Interpretation in the Elliott Case. A Brilliant Strategy but an awful (mid long term) outcome”, Hoftsra Law Review, 2011, Vol. 40, pp. 39-63.

http://www.hofstralawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/BB.4.Olivares-Caminal.final_.pdf

[5]Conversations with various Argentine officials over the February to June 2014 period.

[6] “Don’t worry about an Elliott vs Argentina precedent”, January 11, 2013, http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2013/01/11/dont-worry-about-an-elliott-vs-argentina-precedent/

[7] “US snubs out legal cigar transaction.” Copenhagen Post, February 27, 2012. http://cphpost.dk/news/us-snubs-out-legal-cigar-transaction.898.html

Wall Street Journal Uses Bogus Numbers to Smear Argentine President

By Jake Johnston and Mark Weisbrot | Center for Economic and Policy Research | August 6, 2014

Last week the Wall Street Journal had a front page article on the net worth of Argentina’s first family since 2003, the year Néstor Kirchner was elected president. Based on financial disclosures with Argentina’s Anti-Corruption Office, the Wall Street Journal reported that, “the couple’s net worth rose from $2.5 million to $17.7 million” between 2003 and 2010. Implying that such returns must involve some sort of corruption, the Journal writes, a “lot of people in Argentina want to know where that money came from.”

But there is a serious problem with the way the data are presented here. The Journal is reporting the Kirchners’ net worth in dollars, without adjusting for local inflation. This makes the increase look much bigger than it is, since Argentina had cumulative inflation of nearly 200 percent during these years, according to private estimates.

If the Wall Street Journal had taken inflation into account then the Kirchner’s net worth would have looked quite different. From $2.5 million in 2003, the Kirchners’ real net worth increased to around $6.1 million in 2010.

Simply adjusting for inflation takes away more than three-quarters of the Kirchners’ gain. Should the Journal have known this and adjusted for inflation? The question answers itself. We won’t speculate about anyone’s motives.

But inflation is not the only thing to take into account. The Argentine economy also grew very fast during this period, and was coming out of a depression in which asset prices were severely depressed. So when readers see this kind of an increase in nominal dollars, they are also not thinking about how much nominal asset prices in general increased in the Argentine economy during this time. A fair comparison for the increase in the Kirchners’ wealth would be to ask, how did they do as compared to someone who just put their money in the Argentine stock market in 2003 and left it there during these years?

In nominal pesos, using the Wall Street Journal analysis, the Kirchners’ net worth increased from 7.4 million pesos to nearly 70 million pesos between 2003 and 2010, an average annual increase of 37.7 percent in nominal (not inflation-adjusted) terms. The Argentine stock market, known as the Merval, increased at an average annual rate of 31.1 percent – in nominal terms — between 2003 and 2010. So, the Kirchners beat the market, but not by all that much. Where is the news here?

The importance of this kind of misrepresentation should not be underestimated. Many people will see the numbers at the top of the page, and in the graph accompanying the article, and assume that the Kirchners must have done something illegal in order to accumulate these gains. They will not have the inclination or time to do the research necessary to discover what is wrong with these numbers. The Journal, considered a credible news source, will be used by the opposition media – which is most of the media in Argentina – to accuse the president of corruption. Many people are cynical, and they will believe the accusations.

Russia backs Argentina’s call to curb Western dominance

Press TV – July 13, 2014

Russian President Vladimir Putin has endorsed a call by his Argentinean counterpart Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner to curb Western dominance in international politics.

Putin gave his support during a meeting with Kirchner in the Argentinean capital, Buenos Aires, on Saturday.

The Russian leader also said Moscow and Buenos Aires share a close view on international relations.

During the meeting, Kirchner emphasized that global institutions must be overhauled and made more multilateral, adding, “We firmly believe in multipolarity, in multilateralism, in a world where countries don’t have a double standard.”

In addition, the two leaders discussed military cooperation and oversaw their delegations signing a series of bilateral deals, including one on nuclear energy.

Putin’s visit to Argentina is part of his six-day tour of Latin America aimed at boosting trade and ties in the region, according to Russian state media.

The Russian leader’s trip will next take him to Brazil, where he is scheduled to attend the gathering of the economic alliance, BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), in Brazil on July 15 and 16.

Putin’s Latin American tour began on July 11 in Cuba, where he met with President Raul Castro and his brother, Fidel Castro. During his stay in the capital, Havana, Putin signed a law writing off 90 percent of Cuba’s USD 35-billion Soviet-era debt.

Following his visit to Cuba, Putin made a surprise visit to Nicaragua, where he held talks with President Daniel Ortega.

Argentina to appeal recent court ruling over AMIA case

Press TV – May 16, 2014

Argentina has vowed to appeal a decision by a federal court that rejected an agreement between the Latin American country and Iran over a joint probe into a bombing of a Buenos Aires Jewish center.

On Thursday, an Argentinean federal court struck down a 2013 agreement between the South American country and Iran to jointly investigate deadly attacks on a Jewish center in Argentina in 1994.

Alberto Nisman, a prosecutor in the investigation of the AMIA center explosion, in which 85 people were killed, had argued in his appeal to the court that the 2013 agreement constituted an “undue interference of the executive branch in the exclusive sphere of the judiciary.” The ruling by the federal court against the agreement said that it was illegal and ordered Argentina not to go ahead with it, according to the Reuters.

After the decision was announced, Argentina’s Foreign Minister Hector Timerman said that the ruling was “a mistake” and that the government will take the case to the country’s Supreme Court of Justice.

“I would like to say that the judges take stock in what their mistake means at a national level and at an international level,” Timerman said. “Regarding the decision, Argentina will appeal the mistake and, if necessary, take it to the nation’s Supreme Court of Justice,” he added.

Meanwhile, Justice Minister Julio Alak also said that a final decision was left to the Supreme Court. “The ultimate interpreter of the constitution will be the Supreme Court,” he said.

Under intense political pressure imposed by the US and Israel, Argentina formerly accused Iran of having carried out the 1994 bombing attack on the AMIA building. AMIA stands for the Asociacion Mutual Israelita Argentina or the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association.

Iran has categorically and consistently denied any involvement in the terrorist bombing.

Last January, Tehran and Buenos Aires signed a memorandum of understanding to jointly probe the 1994 bombing.

La Plata MEKOROT deal suspended

The agreement with MEKOROT in La Plata has been suspended! Now we continue, in the rest of Argentina…

Palestinian Grassroots Anti-apartheid Wall Campaign | March 7, 2014

CTA, ATE, Federación de Entidades Argentino-Palestinas (Federation of Argentinian-Palestinian Entities) and Stop the Wall announced the suspension of the shady business with Mekorot, a water treatment plant that would have fuelled Israeli apartheid in Palestine and sought to export it to La Plata in Argentina.

On January 11 2011, the governor of Buenos Aires province, Daniel Scioli, announced, after visiting Israel, that they would tender the building of a regional water treatment plant in La Plata. The contract worth US$170 million was awarded to a consortium of business conformed by the Israeli Water Company MEKOROT, ASHTROM BV (Spanish-Israeli firm) and the Argentinian “5 de Septiembre SA”, a company in which members of the Sindicato de Obras Sanitarias de Buenos Aires (SOSBA), which owns the 10% of the national and provincial Aguas de Buenos Aires (ABSA), participate.

Since 2011, Palestinian organizations, ATE-CTA unions, other civil society organizations and MPs mobilized against this contact. During more than 3 years, they informed the public about Mekorot’s criminal actions in Palestine and investigated the consequences that Mekorot would cause in Argentina.

In a joint effort, they denounced that public Argentinian money would benefit Mekorot and, through this, finance Israeli apartheid in Palestine. The accusations that Mekorot implements apartheid in Palestine are based on reports by Palestinian organizations, the United Nations, and Amnesty International.

Mekorot has been responsible for water right violations and discrimination since the 1950s, when the national water carrier was built which is diverting the Jordan river from the West Bank and Jordan to serve Israeli communities. At the same time, Mekorot deprives the Palestinian communities from access to water. The average consumption in the occupied Palestinian territories is about 70 liters per capita per day – well below the 100 liters per capita per day recommended by the World Health Organization -, while the Israeli consumption per capita per day is around 300 liters. Mekorot has refused to supply water to Palestinian communities inside Israel, despite a decision by the Supreme Court of Israel recognized their right to water. Mekorot is a proud partner of the Jewish National Fund “Blueprint Negev” plan, which will expel 40,000 Bedouin Palestinian citizens of Israel uprooting them from their homes and forcibly moving them to reserves while their lands will be used for Jewish-only settlements in the Naqab/Negev.

Mekorot’s support for illegal settlements is vital and has continued since 1967 when the company took monopoly control over all water sources in the occupied Palestinian territories and caters to the Jewish settlements to the detriment of Palestinian communities. Mekorot participates in the international crime of pillage of natural resources operating about 42 wells in the West Bank, which mostly cater to Israeli settlements. Mekorot also works closely with the Israeli army in the confiscation of irrigation pipes from Palestinian farmers and destruction of sources of water supply for Palestinian communities.

Beyond the street protests and work in the media, the more than 1000 pages of research and technical details compiled by ATE-CTA, served to substantiate questions in the provincial parliament and allow interventions in front of federal human rights organizations. In late 2012, the construction of Mekorot water plant was suspended.

The organizations insisted that Mekorot intended to export its model of discrimination, squandering of water and illegitimate profits developed in Palestine, now to the detriment of the population of Buenos Aires.

To start with, the entire bid was based on a work plan that had previously been designed by Mekorot, which expectably proposed the lowest price.

The expenditure of public money for water treatment plant and the consequent debt of the city with multinationals is unnecessary as the province of Buenos Aires has excellent aquifers. Puelches Aquifer is saturated and to stop drinking its water – as the Mekorot project envisaged – would have produced the elevation of the water table, bacterial contamination, basement flooding and damage to housing foundations. Reports from the ABSA state that the main problem of drinking water lies in the distribution network for which Mekorot wouldn’t have provided a solution.

For the installation in the region, Mekorot required an increase in water tariffs, until almost tripling the costs. The construction of the plant, also implied a further increase of service that would have exceeded 30% and would be paid by all the users in the region.

In terms of water quality, it would have been below the standards determined by the Argentine Food Code. Only part of the population would have had access to safe drinking water while poorer people would have received only tap water posing a risk to their health.

CTA, ATE, Federación de las Entidades Argentina-Palestinos and Stop the Wall thank to all social and political organizations, experts and individuals who contributed to the campaign ‘Mekorot Out of Argentina’. Together we won an important victory for justice in Palestine and the right to water! We continue to fight for our sovereignty over water, against the violence of multinationals and in solidarity with the Palestinian people for freedom, justice and the return of refugees to their homes.

We ask everyone to continue supporting the global movement of boycott, divestment and sanctions against Israel and to fight and prevent other Mekorot contracts in Argentina.

We ask everyone to join the International Week against Mekorot – from 22 to 30 March: “No to water apartheid, Yes for water justice!”

Related articles

Roger Cohen Defecates On Argentina, Gets Many Things Wrong

By Mark Weisbrot | CEPR Americas Blog | February 28, 2014

Roger Cohen, what a disappointment. He is not Tom Friedman or David Brooks, and shouldn’t be insulting an entire nation based on a clump of tired old clichés and a lack of information. Argentina is “the child among nations that never grew up” he writes, and “not a whole lot has changed” since he was there 25 years ago. OK, let’s see what we can do to clean up this mess with a shovel and broom made of data.

For Cohen, Argentina since the government defaulted on its debt has been an economic failure. Tens of millions of Argentines might beg to differ.

For the vast majority of people in Argentina, as in most countries, being able to find a job is very important. According to the database of SEDLAC (which works in partnership with the World Bank), employment as a percentage of the labor force hit peak levels in 2012, and has remained close to there since. This is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Argentina: Employment Rate, Percent of Total Population

Source: SEDLAC (2014).

Source: SEDLAC (2014).

We can also look at unemployment data from the IMF (Figure 2). Of course the current level of 7.3 percent is far below the levels reached during the depression of 1998-2002, which was caused by the failed neoliberal experiment that the Kirchners did away with – it peaked at 22.5 percent in 2002. But it is also far below the level of the boom years of that experiment (1991-1997) when it averaged more than 13 percent.

FIGURE 2

Argentina: Unemployment Rate

Source: IMF WEO (Oct 2013).

Source: IMF WEO (Oct 2013).

How about poverty? Here is data from SEDLAC (Figure 3), which does not use the official Argentine government’s inflation rate but rather a higher estimate for the years after 2007. It shows a 76.3 percent drop in the poverty rate from 2002-2013, and an 85.7 percent drop in extreme poverty.

FIGURE 3

Argentina: Poverty and Extreme Poverty

Source: SEDLAC (2014).

Source: SEDLAC (2014).

Most of the drop in poverty was from the very high economic growth (back to that in a minute) and consequent employment. But the government also implemented one of the biggest anti-poverty programs in Latin America, a conditional cash transfer program.

Finally, there is economic growth. In a terribly flawed article today, the Wall Street Journal reported on a soon-to-be published study showing that Argentina’s real (inflation-adjusted) GDP is 12 percent less than the official figures indicate. (As the article noted, the government, in co-operation with the IMF, implemented a new measure of inflation in January, which should resolve this data problem that has existed since 2007). If we assume that the 12 percent figure is correct, then using IMF data Argentina from 2002-2013 still has real GDP growth rate of 81 percent, or 5.6 percent annually. That is the third highest of 32 countries in the region (after Peru and Panama). And incidentally, very little of this growth was driven by a “commodities boom,” or any exports for that matter.

Despite current economic problems, the country that Cohen ridicules has done extremely well by the most important economic and social indicators, since it defaulted on most of its foreign debt and sent the IMF packing at the end of 2002. This is true by any international comparison or in comparison with its past. Many foreign corporations and the business press, as well as right-wing ideologues, are upset with Argentina’s policies for various reasons. They don’t really like any of the left governments that now govern most of South America, and Washington would like to get rid of all of them and return to the world of 20 years ago when the U.S. was in the drivers’ seat. But there’s really no reason for Roger Cohen to be jumping on this bandwagon.

Western coverage distorts Argentina’s media law

By Ramiro Funez | NACLA | January 28, 2014

Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is currently battling allegations of corruption, and when Argentina’s Supreme Court upheld in October a media law that takes on press monopolies while promoting diversity in media ownership, journalists in the English-speaking North covered it as a blow to press freedom.

The Audiovisual Services Act, originally introduced by Kirchner in 2009, replaced the Radio Broadcasting Law of 1980, put in place by the military regime that ruled the country from 1976 to 1983. The junta used the 1980 law, which promoted the corporatization of news information, to speed up the privatization and monopolization of media in Argentina after independently reported stories undermined military rule, according to the Argentine Information Secretariat’s 1981 report, Argentine Radio: Over 60 Years on the Air

Although the return of constitutional rule in 1983 granted journalists more political freedoms, it largely ignored economic ones. Even after the collapse of the military dictatorship, the 1980 law allowed wealthy business owners, many of whom had been sympathetic to the regime and its pro-market stance, to dominate journalism in Argentina.

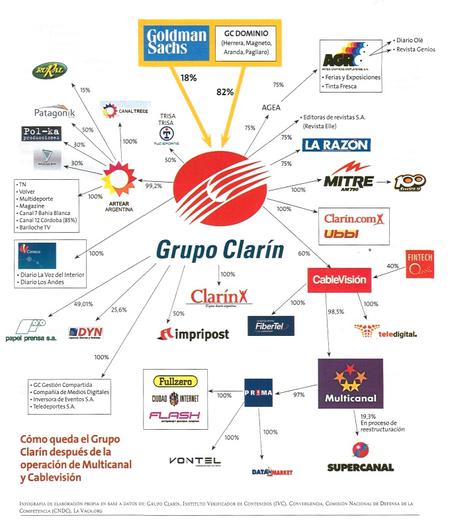

Clarín, founded in 1945 and today one of Argentina’s most recognized daily newspapers, fared well throughout the junta’s administration, eventually surpassing the sales of its main competitor, Papel Prensa. In 1999, the newspaper’s publisher reorganized itself as Grupo Clarín, managing to acquire over 200 newspapers and several cable systems across the country to become Argentina’s largest corporate media organization (Reuters, 10/32912). The organization currently has a market share of 47 percent and holds 158 licenses (Financial Times, 10/29/2013).

The Kirchner-backed media law places limits on the size of media conglomerates in an attempt to diversify ownership of news distribution: media companies will now be limited to a maximum of 35 percent of overall market share. The new law also imposes a national limit of 24 broadcast licenses per company, meaning the group will have to sell off dozens of operating licenses or have them auctioned by the state (Christian Science Monitor, 10/30/13).

Many Western reporters covering Argentina, however, dismiss the danger of concentrated corporate control of journalism, instead focusing on the perceived danger that government regulation of media could silence political opposition—echoing claims made by Grupo Clarín and other private conservative organizations.

U.S. news stories covering the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the media law tended to read like press releases for Grupo Clarín, leading with the consequences it will have on the monolithic media conglomerate. That angle was an easy sell to corporate news outlets that have an interest in focusing on governmental limits on journalism without discussing the problems of a privatized, highly concentrated news market.

The Washington Post (11/1/13), for example, headlined its editorial on the topic “In Argentina, a Newspaper Under Siege,” presenting Grupo Clarín as the victim of a governmental attempt to silence opposition. “Sadly, however, Ms. Fernández and her cronies still pose a threat to the country’s democratic institutions,” the Post wrote:

That became clear Tuesday, when the Argentine Supreme Court, under heavy pressure from the president’s office, upheld a law aimed at destroying one of South America’s most important media firms, Grupo Clarín.

The company operates one of Argentina’s biggest newspapers, called Clarín, which has been one of the few media outlets to challenge Ms. Fernández’s policies. The law would force the company to auction off cable television and Internet businesses that provide most of its revenue, thus reducing potential funding for Clarín’s newsroom.

The article victimizes Grupo Clarín, giving readers the impression the Argentine government established the limits with the intentions of “destroying” the group. Yet the Post fails to mention that the United States also has a history of issuing similar outlet restrictions, like the Telecommunications Act of 1996 that placed a 35 percent limit on market ownership. Although the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) raised that limit to 45 percent in 2003 during a private reevaluation, the agency still has the power to regulate media ownership.

The Post editorial board also linked the media law to Kirchner’s attempts to nationalize major companies in other industries, including travel and energy, saying that she and her late husband, whom she succeeded as president, have sought to “concentrate power in their own hands.”

The Wall Street Journal (11/5/13) chimed in:

In the past few years, the government has shifted nearly all its public advertising money to media outlets that provide it with positive coverage—a move the Supreme Court has condemned, to little effect… Leading newspapers like Clarín and La Nación also say they are suffering from an ad boycott orchestrated by the government—an allegation the government denies.

The Journal ignores the fact that the Kirchner administration continues to direct public advertising to smaller conservative media groups within the Association of Argentine Journalism (CITE); diversified media ownership, rather than ideology or partisan affiliation, is the criterion for government subsidy. Despite the fact that there is an alleged “ad boycott orchestrated by the government,” both Grupo Clarín and La Nación continue to receive more revenue from private advertisers than any other media outlet in Argentina, according to a 2011 report published by the Comisión Nacional de Comunicaciones.

The Associated Press (11/4/13), reporting on Grupo Clarín’s recent decision to break itself up into six parts in order to comply with the law, presented the legislation as little more than a politically motivated attack on one corporation:

The licenses are essential to Clarin’s cable television networks, and synergy between the finances and news content of the group’s TV and radio stations, websites and newspaper are key to its power. Many government supporters want nothing less than Clarín’s defenestration as a viable opponent.

The Associated Press’s framing in the aforementioned article takes the side of Grupo Clarín: They write that Clarín’s unregulated licenses are “key to its power” without airing arguments against the corporate consolidation of public news information. They also make the assumption that Kirchner constituents “want nothing less than Clarín’s defenestration” without providing quotes from pro-media regulation activists in Argentina aside from government officials.

And the Miami Herald (10/23/13) published a column by Roger Noriega of the American Enterprise Institute, formerly of the George W. Bush State Department. Noriega argued that the law was aimed at “silencing the independent media” and that nothing less than “the fate of the free press” was at issue. “Of course, it is all too predictable that these divested media licenses will fall into the hands of compliant Kirchner cronies,” wrote Noriega. “This transparent tactic is lifted from the playbook of leftist caudillos in Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia and elsewhere.”

A quick sift through Noriega’s column reveals that his definition of “independent media” elides the dependency that media organizations like Grupo Clarín and La Nación have on funding from private corporations that have personal profit-making agendas—a dependency that forces both groups to embrace the political ideologies of their sponsors in order to maintain steady revenue. A truly “independent media” would be free of both government and corporate domination. It is also evident that his notions of a “free press” are founded upon free-market, neoliberal principles, championing corporate domination of political news coverage. His tactic of utilizing the term “free press” in correlation with unregulated, monopolized, and corporatized news media seems to hail straight from the playbook of McCarthyist lexicon, to borrow a few words from his comparison.

Overall, corporate journalistic monopolization and the concentration of news media is more of a threat to press freedom in Argentina than government regulation is. The domination of public discourse by media groups with private, corporate interests is dangerous to readers who are oftentimes unaware of the advertising revenue models of organizations like Grupo Clarín; in its obligations to maximize profits, it has strategic incentive to promote the interests of its commerical sponsors rather than the people of Argentina searching for objective news coverage.

Many Western journalists have painted Kirchner as an authoritarian leader desperate for control over news coverage in order to maintain a positive image, without realizing that in modern times, media ownership is just as influential as government suppression of speech. While many conservative Argentines have blindly sided with groups like Grupo Clarín in criticizing the government’s large advertising presence in news organizations that are friendly with the incumbent administration, they have failed to recognize that there is a difference in advertising intentions and content between the Kirchner administration and private corporations: the former publicizes information about social welfare programs available to citizens, while the latter promotes products whose profits benefit the small percentage of Argentines who have seemingly little at stake in quality social programming.

The Supreme Court of Argentina and the Kirchner administration have recognized that progressive interpretations of freedom of speech include democratic and popular control over mass information and national discourse. They have also recognized the need for public diversity in media ownership that fosters economic freedoms within journalism, allowing any citizen, regardless of ideology and economic background, to have just as amplified of an opinion as a corporate news organization does—all without violating political rights.

Organizations that have claimed otherwise, or that echo the cries of victimization made by Grupo Clarín, fail to analyze alternative qualities of freedom of speech.

Ramiro S. Fúnez is a Honduran-American political journalist and activist earning his master’s degree in politics at New York University. Follow him on Twitter at @RamiroSFunez.

Related article

Argentina to summon Israeli ex-envoy over AMIA comments

Press TV – January 4, 2014

Argentina is to summon former Israeli envoy to Buenos Aires to explain his recent comments that the Tel Aviv regime has killed most of the perpetrators behind the bombing of the AMIA Jewish community center in the Latin American country in the 1990s.

In an interview with Buenos Aires-based Jewish News Agency (Agencia Judía de Noticias) on Thursday, Itzhak Aviran, who was the Israeli ambassador to Argentina from 1993 to 2000, said Israeli security agents operating abroad have “killed most of those who had carried out the attacks.” Aviran also accused the Argentinean government of not doing enough “to get to the bottom” of the incident.

AMIA case special prosecutor Alberto Nisman said on Friday that “I am surprised at his statements. I have ordered a testimonial statement. I would like to know how he is sure about it, who were these people and which proof he has.”

“What he is saying is that the perpetrators of the attacks are identified by name and surname,” Nisman said, adding that the process to query the Israeli ex-envoy should not take longer “than a month, or a month and half.”

Israel has dismissed Aviran’s comments as “complete nonsense.”

Under intense political pressure imposed by the US and Israel, Argentina formally accused Iran of having carried out the 1994 bombing attack on the AMIA building that killed 85 people.

AMIA stands for the Asociacion Mutual Israelita Argentina or the Argentine Israeli Mutual Association.

The Islamic Republic has categorically and consistently denied any involvement in the terrorist bombing.

Tehran and Buenos Aires signed a memorandum of understanding in January, 2013, to jointly probe the 1994 bombing.

The Israeli regime reacted angrily to the deal a day after it was signed. “We are stunned by this news item and we will want to receive from the Argentine government a complete picture as to what was agreed upon because this entire affair affects Israel directly,” Israeli Foreign Ministry spokesperson Yigal Palmor said on January 28.

On January 30, however, Argentina said Israel’s demand for explanation over the “historic” agreement is an “improper action that is strongly rejected.”