Dayton At 30: US Betrayal Old And New

By Kit Klarenberg | Global Delinquents | December 30, 2025

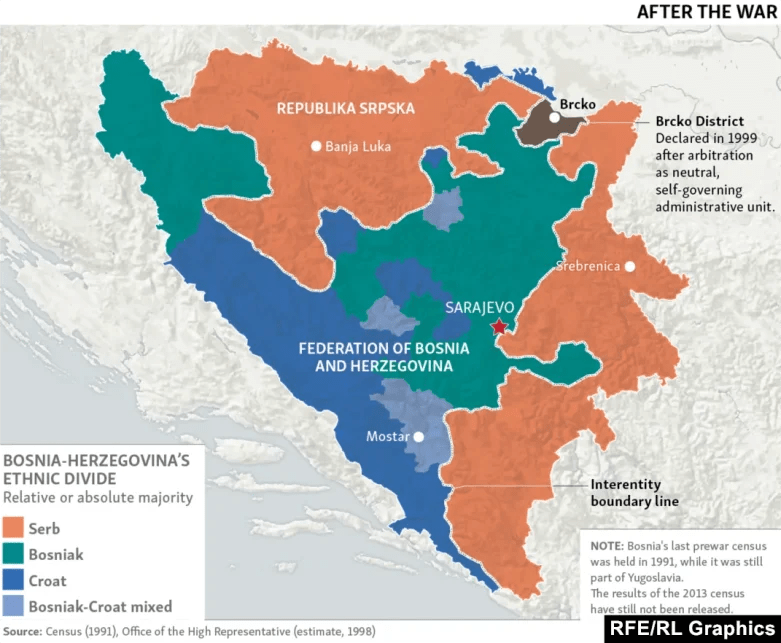

December 12th marked the 30th anniversary of the Dayton Accords’ signing, which ended the Bosnian civil war after three-and-a-half years of brutal fighting. While consistently hailed in the mainstream as a US diplomatic triumph, the agreement imposed a discriminatory and unlawful constitution upon Sarajevo enshrining division between the country’s three main ethnicities – Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs – and a Byzantine political system, while carving the country into two separate ‘entities’. Bosnia has constantly teetered on collapse ever-after, sustained purely by prolonged NATO and UN occupation.

Moreover, the Dayton Accords represented a rank betrayal of Washington’s Bosniak allies. In the conflict’s leadup, the US consistently encouraged them – led by President Alija Izetbegobic – to reject peace talks. After the war’s eruption, he was emboldened to keep fighting and spurn negotiations, strung along with effusive public support from US officials, and covert military assistance. Come Dayton, the Bosniaks were forced to accept a far worse settlement than any previously proffered. Parallels with the Ukraine proxy war are ineluctable.

The Bosnian conflict’s greatest tragedy is it could’ve been avoided not only without a shot being fired, but no territorial carve-up or ethnic partition of any kind. In the years before its April 1992 outbreak, numerous attempts were made to reach an equitable settlement negating any prospect of war. In summer 1991, as Yugoslavia was beginning to rapidly disintegrate, representatives of Izetbegovic met with Bosnian Serb leaders in Belgrade, to discuss the then-republic’s future.

The two sides hammered out a simple but ingenious plan. Bosnia would be a sovereign, autonomous, undivided state, in confederation with Serbia and Montenegro. Bosniak-majority territory within Serbia would also be ceded to Sarajevo’s administration. The agreement emphasised the necessity of the republic’s diverse population “living together in freedom and full equality.” Bosnia would remain part of Yugoslavia, albeit under a revised federal system, in which the country’s constituent parts were essentially independent, and “completely equal”.

Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic not only agreed to the plan, but further proposed Izetbegovic be the new Yugoslavia’s first federal President for a five year term, invested with the power to appoint military leaders and diplomats, and serve as the country’s head of state. Izetbegovic’s representatives signed off on the agreement, before returning to Sarajevo. Initially, the Bosniak leader was on board. However, according to numerous sources, Izetbegovic withheld his formal endorsement pending a planned trip to the US.

Upon his return, Izetbegovic rejected the deal. This was neither the first nor last blatant example of Stateside officials torpedoing fruitful peace efforts before, and during, the war. The conflict itself was triggered by the personal interventions of Warren Zimmermann, US ambassador to Yugoslavia. Echoes of Boris Johnson’s April 2022 sabotage of peace talks between Russia and Ukraine are palpable. In early 1992, in a desperate final bid to prevent conflict, the EU drew up the “Lisbon Agreement”.

Under its terms, Bosnia would be an independent country completely separate from Yugoslavia, divided into “cantons” dominated by whichever ethnic/religious community was most populous locally. Bosniaks and Serbs were allocated 43% of the state’s territory each, and Croats the remainder. The three were to share power nationally, with a weak central government. It was signed by leaders of the republic’s ethnic groups in March that year.

However, Izetbegovic was concerned the plan partitioned Bosnia into distinct entities, with the prospect its Croat and Serb components could secede thereafter. He voiced these concerns to Zimmerman, who told him, “if he didn’t like it, why sign it?” With that blessing – and prospect of US recognition of an independent Bosnia, and economic and military support – Izetbegovic withdrew his signature, sparking war. Zimmermann later reflected, “the Lisbon Agreement wasn’t bad at all.” Indeed, it was considerably better than the future Dayton Accords, for all concerned.

‘Military Situation’

Bill Clinton made the Bosnian conflict a core plank of his 1992 Presidential election campaign. Attacking incumbent George H. W. Bush for inaction on the crisis, Clinton proposed a variety of aggressive policies, including arming the Bosniaks to the teeth, and outright US military intervention in the form of airstrikes. Expectation was high Washington’s approach to Bosnia would become considerably more belligerent immediately upon Clinton’s inauguration, if he won the vote.

Clinton’s rhetoric shocked the Bush administration, which branded his warlike pledges “reckless”. Little did the public know, this perspective was entirely in line with US intelligence thinking. A vast trove of declassified files related to the Bosnian war show the CIA and other spying agencies were steadfastly opposed to greater US involvement from the conflict’s earliest stages. After Clinton’s victory, the US National Intelligence Council produced a comprehensive explainer guide for his transition team on the civil war.

The document laid out all manner of issues associated with different strategies Clinton had mulled on the campaign trail. For example, US intelligence assessed how, “even with additional weapons,” Bosnian government forces “could not substantially alter the military situation.” Increasing arms deliveries would produce “greater casualties but no resolution of the conflict,” and “attempting to reclaim all of the territory the Bosnian Serbs now occupy would require massive Western military intervention,” including a ground invasion.

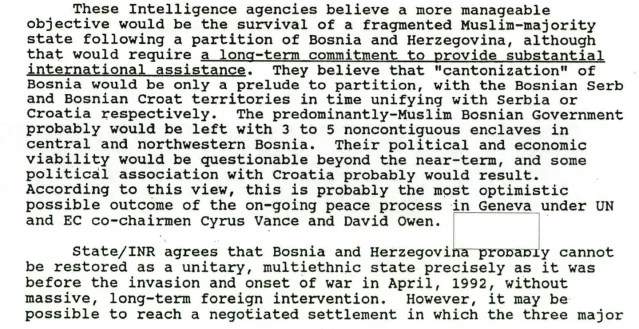

Overall, US intelligence believed “the most optimistic possible outcome” was preserving a “fragmented Muslim-majority state following a partition of Bosnia.” This was the exact substance of a peace plan then-under consideration, drawn up by European Community and UN negotiators David Owen and Cyrus Vance. Records of a secret February 1993 meeting between senior US government, intelligence and military officials show attendees were determined to covertly wreck the Vance-Owen plan – which granted Bosnian Serbs 43% of the country – while remaining ostensibly committed to its implementation.

One means by which Washington ensured Vance-Owen failed was by consistently refusing to publicly rule out military action, while secretly funnelling vast arms shipments – in breach of a UN embargo – and foreign fighters to Sarajevo. US intelligence repeatedly warned the White House such actions steeply increased the Bosnian government’s expectations of subsequent Western military intervention on their side. This meant Sarajevo would be resistant to consider let alone accept peace agreements, even when badly losing the conflict.

US military intervention finally did come, in the form of NATO’s Operation Deliberate Force, an 11-day saturation bombing of Bosnian Serb territory conducted over August/September 1995. This finally set the stage for the Dayton talks, which commenced November 1st that year, after all sides agreed to “basic principles” underpinning negotiations. Bosniak representatives had every reason to expect the US to unflinchingly fight their corner – but they were in for a nasty surprise.

‘Moral Position’

From the Dayton talks’ inception, it was clear Washington harboured little favouritism towards the Bosniaks. After two weeks, no progress had been made, despite Serb delegate Slobodan Milosevic being eager to make significant concessions. The US also offered Sarajevo numerous inducements, including a controversial program to arm and train Bosniak forces over subsequent years. Central to Izetbegovic’s intransigence was the US-endorsed peace agreement splitting Bosnia into two ‘entities’, with a Serb-majority internal republic – Republika Srpska – governing 49% of the country.

In other words, Dayton handed the Bosnian Serbs more territory than any prior proposed peace settlement, while effectively entrenching the very partition that influenced Izetbegovic’s resistance to the Lisbon Agreement, and produced all-out war. His opposition to the Accords was nonetheless battered down by the blunt-force threat of all-out US betrayal if he refused to acquiesce. On November 15th, a series of “talking points” were provided to Clinton’s National Security Advisor Tony Lake, in advance of a personal meeting with Izetbegovic.

Lake was instructed to spell out dire “consequences” the Bosniaks would suffer, if they failed to sign off on the US-dictated peace plan. He would relay how Clinton understood Izetbegovic was in an “extremely difficult” position, but the US President was “disappointed… Dayton has failed to produce agreement” after so much talk. “If we are successful at Dayton, the President will help you make [the] case that peace achieved at Dayton was just,” Lake was directed to say. He would add:

“Territorial proposals are not perfect, but…likely best deal possible. More fighting will be costly with no guaranteed results. Time for peace…Many in [the] US could use failure in Dayton as [an] excuse to disengage from peace process and abandon [the] moral position we have defended to this point.”

If Izetbegovic’s government was “unwilling to complete [a] peace agreement that Serbs can accept” endorsed by Washington, Lake would threaten there would be “no US forces on the ground, NATO implementation, and economic aid and reconstruction package.” Furthermore, US Congress would not approve, and the Clinton administration would not request, the “equip and train” program for Bosniak forces. UN peacekeepers would also “withdraw” from the country, meaning “Bosnia could find itself without any form of military support from the West.”

“Much at stake for you [and] Bosnia,” Lake’s talking points for Izetbegovic concluded. “Encourage you to think carefully about Dayton… a very good result is within reach; do not let it slip away.” Successfully coerced, Izetbegovic and his team signed the Accords. Dayton’s terms have been a sore source of contention for Bosniaks ever since. Veteran Bosnian politician Haris Silajdzic, a key Izetbegovic acolyte and Bosniak President 2006 – 2010, has dedicated much of his political career to invalidating them.

In a secret March 2007 discussion with the US embassy in Sarajevo, Silajdzic ranted, “we had to sign Dayton with a gun at our heads.” Fast forward to today, and Kiev stares down a similar barrel. Washington pressures Volodymyr Zelensky to accept peace at all costs. This could include major territorial concessions, among other hitherto unthinkable compromises. If only Kiev had implemented the Minsk Accords – and learned the obvious lessons of the Bosnian war – this invidious position could’ve been avoided entirely.

Bosnian war propaganda resurgence: the last hurrah

By Stephen Karganovic | Strategic Culture Foundation | November 26, 2025

Most were under the impression that the war in Bosnia was behind us. The conflict in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s was characterised by the use of the crudest kind of propaganda, but it was undoubtedly in the Bosnian theatre that the crassness was the most pronounced.

It turns out however that for those who had politically benefitted from that war, or who think that they might still benefit a little more with an improvised replay of the propaganda techniques that were successful thirty years ago, the war in Bosnia remains the gift that keeps on giving.

Evidence of that is the intense media barrage, reminiscent of the 1990s, about alleged “Safari tourism” in the hills overlooking besieged Sarajevo. The story goes that wealthy psychopaths from Italy and other Western countries were paying enormous fees, running up to 100,000 euros in today’s money, eagerly collected by the Bosnian Serbs who held the hillside positions, for permission to shoot and kill defenceless civilians in the besieged city below.

The macabre “spirit cooking” dinners organised for the perverse pleasure and entertainment of the crème de la crème of Western elite circles, not to mention numerous other similar examples of depravity, make the Sarajevo allegation seem plausible, in principle at least. There are no moral factors on the side of this scenario’s Western perpetrators that would have prevented it from happening, assuming that the conditions were propitious.

That having been said, agreement that something could have happened is not an automatic confirmation that it actually did. Evidence is still needed to bridge the gap between a theoretical possibility and a demonstrated fact. For purveyors of propaganda, however, bridging that gap is not a major concern because their craft operates on emotional manipulation, not empirical proof. Their task is accomplished once they have successfully embedded in the public’s mind the subconscious impression they desired to implant there.

How does the Sarajevo “safari tourism” allegation stack up when examined with a reasonable degree of scepticism and the application of rigorous standards of proof? Like most propaganda constructions, it falls apart.

The first thing one notices that calls for extreme caution is that the alleged events occurred in the mid-1990s but are being brought to light and, it is claimed, investigated by the Milan Public Prosecutor’s Office only now, in 2025, more than thirty years later. The Bosnian war ended after the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement in December of 1995 and soon thereafter conditions were sufficiently normalised in Bosnia and Herzegovina. There were no serious impediments to conducting war crimes investigations and numerous agencies and institutions did precisely that. Shooting safaris where the targets were human beings would be a crime against humanity of extraordinary gravity. A reasonable explanation is required why no police or judicial organs investigated these heinous allegations soon after those events are said to have happened, whilst witnesses could still be found with relative ease and, just as importantly, forensic evidence might still have been intact. That first and most obvious question is not even asked, let alone answered by anyone.

The other key unasked (and therefore also unanswered) question is about the source for these belated allegations. It is a documentary film “Sarajevo Safari,” released in 2022. We now come to the interesting part. The film was financed by Hasan Čengić, one of the founders of the Democratic Action Party of Bosnia’s war-time President Alija Izetbegović. Mr. Čengić therefore is by no means an impartial source. During the war he was one of the principal funds and arms procurers for Izetbegović. The film’s producer is the Slovenian film director Franci Zajc who during the conflict created numerous documentaries which uniformly presented only the Serbian side in an unfavourable light. Zajc also happens to be one of the only two supposedly percipient witnesses of this safari tale. The other alleged witness is Mr. Čengić himself who, however, is unavailable for cross examination because he passed away in 2021.

Some would argue that Zajc is a shady witness because of his extravagant claims that during the conflict in Bosnia he was an agent of Western intelligence agencies but that nevertheless the Serbs allowed, and in some versions even invited, him to observe these morbid proceedings. Why the Serbs would allow a hostile witness like Zajc to observe them in such a compromising situation is unexplained. Be that as it may, these are the only two ocular witnesses of the Sarajevo “tourist safari” events known so far. One of them claims and the other, Čengić, almost certainly did have intelligence connections. These are the exclusive sources for a sensational story that is making headlines in the collective West media and has even attracted the attention of one of the frequent contributors to this portal.

Yet even these scant sources for an event of major significance, if it is authentic, are not in complete harmony about an important detail of their story. Zajc has claimed that wealthy foreigners paid huge amounts of money to the besieging Serbs to shoot civilians and that they were provided with sniper weapons for that purpose by their Serbian hosts. Čengić on the other hand claimed before his death that foreigners were paying trifling fees for the morbid privilege and brought their own weapons.

But there are more problems with this affair. It is said that the Milan Public Prosecutor’s Office is conducting an investigation. That may well be the case. But the important question that anyone with legal training will immediately ask is what is the statute of limitations for murder in Italy? It happens to be 21 years. That means that if the imputed crime was committed more than twenty-one years before apprehension, even if the perpetrator were to be identified and linked to the crime he could not be prosecuted. The alleged offences date back to the mid-1990s, which means that the Italian statute of limitations has expired and nobody any longer can be brought to court to answer charges of sniping at civilians from the hills that surround Sarajevo. If the Prosecutor in Milan is indeed investigating, would he not be wasting his time?

If the motive were purely judicial, he certainly would be. But if the motive is predominantly political, not necessarily so.

Furthermore, even if statutory obstacles could be overcome, for instance by reclassifying the offence as a crime against humanity for which there is no statute of limitations instead of treating it as a simple murder under Italian law, there would still be a problem. For a conviction to be achieved under either indictment, beyond the necessity of personally identifying the shooters, which is the sine qua non, to actually convict them they would have to be directly linked to a lethal outcome on the ground. For an indictment to be viable, victims would have to be identified as well, almost thirty years after the fact. Shooting with a sniper weapon is not a crime unless it results in someone’s death. For culpability to be established, a forensic investigation would have to be conducted to determine for each imputed victim the cause and manner of death, and bullets which struck the victims would have to be provably traced to the weapons that were in the hands of the perpetrators at the time of shooting, almost thirty years ago. Does that seem like a feasible undertaking for the Milan Prosecutor, no matter how competent he may be? That is doubtful.

The media frenzy that has erupted around allegations of war-time tourist safaris on civilians in Sarajevo recalls the worst propaganda excesses of that conflict. Their most notable feature was that critical questions were not being asked and that few and largely unverified facts were force-fitted into a Procrustean propaganda matrix. When subjected to close scrutiny most of these claims almost always are found to be uncorroborated and spurious.

That certainly seems to be the case with the Sarajevo Safari story, regardless of the fact that the collective West media are having a field day expanding on it in endless and strikingly imaginary detail.

The Safari story will soon die a natural death once it is concluded that its political purpose has been achieved. The purpose is not to convict anyone because given the complete unavailability of any evidence, even under the most rigged trial conditions that would be nearly impossible. It is, rather, to create a sinister impression that would further discredit the Serbian entity in Bosnia, the Republika Srpska, for colluding with depraved individuals and facilitating their heinous behaviour in return for money. The successful dissemination of such an impression will serve as an additional argument for the liquidation of Republika Srpska and will indirectly validate other heinous allegations made at the expense of the Serbian side during the Bosnian conflict. That explains the timing.

As for the Milan Prosecutor’s Office, it will quietly drop its investigation for some specious bureaucratic reason that no one will ever question. And there on the legal level the matter will end. There will be no facts, only emotionally charged impressions.

Republic of Srpska in crosshairs again

By Stephen Karganovic | Strategic Culture Foundation | August 20, 2025

The political siege of Russia’s tiny Balkan ally, the Republic of Srpska, an autonomous entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina, is gaining momentum. On Monday, 18 August 2025, two significant developments took place. The first is that the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina denied the appellate motion of Milorad Dodik to quash the decision of the Central Electoral Commission cancelling his Presidential mandate. That is the endpoint of the legal proceedings against Dodik on charges of disobeying the orders of Bosnia’s de facto colonial administrator, German bureaucrat Christian Schwarz. The other significant event was the resignation, on the same day, of Republic of Srpska’s Prime Minister, Radomir Višković. Višković was appointed by Dodik in 2018 and was considered a loyal aide to the President. The impact of his hasty departure, on exactly the same day that, by collective West reckoning, Dodik ceased to be President and became a private person, is yet to become fully visible. But the fact that he did not even wait for a “decent interval” (Kissinger’s famous words from another context) before abandoning ship cannot be regarded but as politically ominous.

For a proper understanding of the roots of the grave constitutional and political crisis affecting not just the Republic of Srpska but Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole it would be worthwhile to briefly review the violations of fundamental international and domestic legal principles that had given it rise.

At the conclusion of the civil war in Bosnia, in late 1995, a peace agreement was hammered out in Dayton, Ohio, between the three Bosnian parties with the participation of the major Western powers and interested neighbouring countries. The agreement provided for a sovereign Bosnia and Herzegovina organised as a loose confederation of two constituent ethnically based entities, the Republic of Srpska and the Muslim-Croat Federation. The country had become a member of the UN in 1992 when it separated from Yugoslavia. That membership continued and served as an additional guarantee of its sovereign status as a subject of international law.

One of the provisions of the Dayton Agreement was that the UN Security Council would select and approve an international High Representative with a year-long mandate. That official would be authorised to “interpret” such sections of the Peace Agreement concerning the meaning and application of which the parties were unable to agree. The initially one-year mandate envisioned for the High Representative by inertia became extended indefinitely so that, after nearly thirty years of peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, that office still exists.

In December of 1995, shortly after the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement, a self-created entity called the Peace Implementation Council (PIC) was organised by 10 collective West countries and international bodies to “mobilise international support for the Agreement.” Russia originally was invited to be a member, though in its parlous political condition of the 1990s it was always outvoted by Western “partners,” but it has since withdrawn. Also by inertia, at its 1997 meeting in Bonn, Germany, PIC expanded the scope of its own activity vis-à-vis Bosnia to include proposing to the UN Security Council a suitable candidate for High Representative when that post would become vacant. But more importantly, acting motu propio it radically augmented the powers that the High Representative in Bosnia could exercise, to a level not contemplated in the Dayton Agreement. According to the “Bonn Powers” granted to him by PIC at the 1997 meeting, he would no longer be confined to “interpreting” the Dayton Agreement but would also be invested with unprecedentedly robust authority to annul and impose laws in Bosnia and Herzegovina and to dismiss and appoint public officials.

In the Wikipedia article on this subject, of unspecified authorship but written evidently by someone sympathetic to this method of governance, it is stated that “international control over Bosnia and Herzegovina is to last until the country is deemed politically and democratically stable and self-sustainable.” Who decides that is left conveniently unsaid, but the arrogant formulation constitutes a text-book definition of a colonial protectorate.

As a result of these manipulative rearrangements of the peace framework codified in the Dayton accords, acting by its arbitrary volition, PIC, a self-authorised group of countries, conferred on the Bosnian High Representative a drastic expansion of executive authority, which was without basis either in the Dayton Peace Agreement or in international law. Or in the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, for that matter.

Article 3.3.6 of that Constitution prescribes that “general provisions of international law are an integral part of the legal order of Bosnia and Herzegovina.”

As cogently argued by Serbian constitutional law professor Milan Blagojević, the chief of the general precepts of international law is the principle of sovereign equality of member states of the United Nations, as enshrined in Article 2 of the Charter. That principle is the reason why Article 78 of the Charter prohibits the establishment of a trusteeship, or protectorate, over any member state of the United Nations.

As Prof. Blagojević further points out, that means that both the Charter of the United Nations and the Constitution of UN member state Bosnia and Herzegovina, which incorporates it by reference, prohibit anyone other than the competent organs of the member state to promulgate its laws or to interfere in any other way in the operation of its legal system.

But that is exactly what Christian Schmidt, the individual currently claiming to be the High Representative in Bosnia, has done, provoking the crisis in which the Republic of Srpska is engulfed. In 2023, he arbitrarily decreed that a new provision of his own making and without need for parliamentary approval should be inserted in Bosnia’s Criminal Code, making non-implementation of the High Representative’s orders a punishable criminal offence. Incidentally, not only are the “Bonn Powers” that Schmidt invoked in support of his invasive interference in Bosnia’s legal system questionable, but so is his own status as “High Representative.” Fearing a Russian veto, his nomination was not even submitted to the UN Security Council, so that the Council never exercised its prerogative of approving or rejecting it.

Noticing the flagrant violation of applicable international and domestic legal norms, shortly thereafter in 2023 the Parliament of the Republic of Srpska passed a law making decrees of the High Representative that trespassed his original authority under the Dayton Peace Agreement null and void and unenforceable on the Republic’s territory. That bold but perfectly reasonable law, adopted by a duly elected Parliament, gave great offence to the guardians of the “rules based order.” Acting in his capacity as President, and in defiant disregard for Schmidt’s explicit warning to desist, Milorad Dodik signed the law, giving it legal effect.

The prosecution case against Dodik in the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina stemmed from that act of boorish defiance of orders that clearly were of questionable provenance and even more doubtful legality. But as a result, Dodik was nevertheless arbitrarily deposed as President and is not allowed to run for public office in his country for the next six years.

The range of choices now before Dodik and, more importantly, the Republic of Srpska and the million Serbs who live there, is extremely limited. The Electoral Commission which, like all organs of Bosnia’s central government, answers to whoever has usurped the office of High Representative, will now have up to ninety days to call a snap election to fill the post of Republika Srpska President. As expounded in a previous article, under the current rules, and with Dodik’s forced departure from the political scene, it should not be difficult to “democratically” install a cooperative figure like Pashinyan in Armenia, who would be amenable to implementing collective West’s agenda. The key elements of that long-standing agenda are the lifting of Republika Srpska’s veto on Bosnia’s NATO membership and governmental centralisation for the convenience of the collective West overlords. In practice, the latter means divesting the entities of their autonomy and consequently of their capacity to cause obstruction.

Dodik has announced ambitious plans to counter these unfavourable developments. He intends first to call a referendum for Republika Srpska voters to declare whether or not they want him to continue to serve as President, followed by another referendum for Serbs to decide whether they wish to secede or remain in Bosnia and Herzegovina. But these manoeuvres and aspirations may be too little, too late. As the abrupt resignation of his Prime Minister presages, there may soon begin a stampede of other officials eager to distance themselves from Dodik, anxious for their sinecures and fearful of being prosecuted – like their erstwhile President – for disobedience. Once private citizen Dodik has been divested of effective control over his country’s administrative apparatus, threats of secession or referendums to demonstrate his people’s continued loyalty will ring hollow and are unlikely to impress, much less achieve, their purpose.

Countdown begins for the Republic of Srpska

By Stephen Karganovic | Strategic Culture Foundation | August 9, 2025

The chronic political crisis in the Republic of Srpska, one of two ethnically-based constituent entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, has taken a grave turn for the worse. On 26 February, the illegitimate federal Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, acting under the thumb of the equally illegitimate international “High Representative,” who is actually the colonial governor in the supposedly sovereign country, issued a politically tainted verdict against Milorad Dodik, President of the Republic of Srpska. Dodik had been put on trial on the spurious charge of “defying” the edicts of the High Representative. To no one’s surprise, he was found guilty. The court sentenced him to one year’s imprisonment and banned him from holding public office for six years. Practically all avenues of appeal having now been exhausted, the Electoral Commission of Bosnia and Herzegovina wasted no time to meet on Wednesday 6 August and to officially annul Milorad Dodik’s Presidential mandate. The Commission now has ninety days to organise a snap election to fill the vacancy it had capriciously created in the post of President of the Republic of Srpska.

Milorad Dodik thus joins other European political figures, such as Marine Le Pen in France and Kalin Georgescu and Diana Sosoaka in Romania, who have been disqualified from participation in politics for professing banned opinions and advocating proscribed political positions. The pattern is exactly the same and it is being repeated. It no longer matters what their respective electorates prefer and for whom they wish to vote. The voters are denied the opportunity to express their preference if there is the slightest possibility that they might elect someone whose policies are incompatible with the objectives of the unelected and unaccountable globalist deep state cabal which, in the collective West and its dependencies, is the real government.

The farce of “democracy” and “rules based order” can be contemplated in microcosm in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the sordid political drama which is the subject of this report is unfolding. Supposedly an independent country since the signing in 1995 of the Dayton agreement which ended the civil war, and featuring all the outward trappings of “Western democracy,” Bosnia and Herzegovina has in fact been ruled in neo-colonial fashion by a High Representative who is appointed by the “international community” and invested with dictatorial powers. Over the years, the scope of the High Representative’s authority has been increasing steadily and by design at the expense of the autonomous ethnic entities. Officials in that position promulgated and annulled laws, ousted democratically elected local officials who were deemed uncooperative, and arbitrarily imposed institutions they themselves invented, which are not contemplated either in the Bosnian Constitution or the Dayton Peace Agreement. The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina which tried and convicted Milorad Dodik is a conspicuous example of such a constitutionally spurious institution which came into being ex nihilo by decree of a previous High Representative.

To make the irony complete, the credentials of Christian Schmidt, the individual currently claiming to be the High Representative, are as dubious as is the legal standing of the “court” which tried and convicted Dodik. Schmidt’s appointment was accomplished by a sleight of hand on the part of the collective West, never having been submitted for approval to the UN Security Council, as established procedure provides.

The “offence” imputed to Dodik is that he signed into law a measure enacted by the National Assembly providing that decrees issued by the arguably illegitimate High Representative would not be enforced on Republic of Srpska territory. Invoking his alleged powers as High Representative, Schmidt warned Dodik to refrain from doing that and preventively inserted in the Bosnia-Herzegovina criminal code a section which defines non- enforcement of High Representative’s decrees as a criminal offence. In the face of Dodik’s non-compliance, Schmidt ordered the public prosecutor’s office to seek Dodik’s indictment pursuant to the section of the criminal code he himself had created for precisely that purpose. So as matters presently stand, Milorad Dodik has been removed as President of the Republic of Srpska, the office to which he was legally elected by his constituents. That was achieved through a verdict delivered by a constitutionally illegal court acting on the basis of a rogue provision in the criminal code dictated without any legislative input by a foreign official illegitimately exercising a power that he does not have.

It is difficult to imagine, or to stage, a more colossal farce.

There are, of course, solid reasons why for a long time Dodik’s ouster has been insistently sought by the powers that be. His background is shady, like that of most Balkan politicians, but that certainly is not the real reason for their animosity. Initially, in the 1990s, he was in fact the West’s favourite in post-Dayton Bosnia, avidly promoted by Madeleine Albright of all people. The particulars of his road to Damascus conversion and subsequent meanderings certainly bear careful analysis, but the empirical net result of it is that by the time in 2006 that he became Prime Minister Dodik was on the outs with his original mentors. He had now become a forceful advocate of close relations with Russia and a determined opponent of Bosnia’s accession to NATO, an issue over which the Republic of Srpska wields veto power. He further infuriated his former mentors by steadfastly opposing the evisceration of the Dayton Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina and by resisting fiercely the erosion of Republic of Srpska’s autonomous status which is guaranteed by it.

It must be admitted that the collective West has now come within striking distance of achieving its goal to snuff out the Republic of Srpska. The Dodik removal operation seems now to have been brought to its conclusion, and in a way that observes the outward forms of legality, or so it would appear if one does not delve too deeply into the intricacies of the matter. In relatively short order, a snap Presidential election will take place in Republika Srpska. The collective West will concentrate its still formidable resources in that tiny but disproportionately significant point of the globe to ensure that the Republika Srpska Gorbachev is duly elected and can launch the process of its dismantlement and geostrategic reorientation of what is left of it. Mechanisms to accomplish that are already in place and a possible mass boycott of the discontented Serbian population is unlikely to affect anything. The electoral law currently in force does not require that a minimum number of eligible voters should take part for the election to be deemed valid. With reliable formulas of electoral engineering, helped along with copious quantities of cash, even in the event that on election day all patriotic Serbs should stay at home, the “right” candidate might receive only a handful of votes but his “victory” would nevertheless be easily assured. Prompt recognition of the bogus outcome by the “international community” will do the rest.

Like most Balkan politicians, Dodik has failed to prepare another figure of comparable stature who might succeed him and continue what was good in his policies. That failure will soon take its toll because none of the mediocrities and yes men surrounding him has the charisma and attributes that are necessary to prevail in the coming uphill battle to prevent Republika Srpska from falling lock, stock, and barrel into the hands of its enemies.

The failure to prepare however is not to be laid just at Dodik’s but also at Russia’s door. As in neighbouring Serbia and many other places the policy of all eggs in one basket is once again proving to be erroneous and detrimental to Russia’s interests. Non-interference in other countries’ affairs and working with the established authorities is a fine principle, but only in its dogmatically overzealous and ultimately counter-productive application would that exclude the prudent policy of cultivating capable individuals and amicable political forces. They should be there to act when necessary as an effective counterbalance to the ruthless interference that Russia’s unyielding adversaries incessantly and everywhere engage in.

Bosnian Serb leader stripped of presidential mandate, vows to never surrender

Remix News – August 7, 2025

Last Friday, the Bosnian Court of Appeal upheld the initial verdict against the separatist Milorad Dodik, sentencing the Bosnian Serb, who is president of the Republika Srpska, to one year in prison and banning him from holding public office for six years.

The electoral commission subsequently decided to revoke his presidential mandate, writes Magyar Nemzet, and Dodik has 90 days to appeal the decision.

As Remix News has previously reported, Dodik was jailed for going against orders of an international peace-keeping envoy and suspending rulings by the country’s constitutional court.

Dodik has systematically been pulling out of the federal institutions and legal frameworks of Bosnia and Herzegovina, implementing bans on its judiciary and intelligence agency.

The Bosnian Federal Prosecutor’s Office indicted Dodik in August 2023 under a section of the Criminal Code that provides for a prison sentence of six months to five years and a ban from office for up to ten years for an official who fails to comply with, implement, or obstruct the decisions of the High Representative of the international community.

In response to this most recent ruling, Dodik said: “I am not going anywhere, there’s no surrender,” announcing a referendum to determine whether Bosnian Serbs agree with the electoral commission’s decision and whether they should accept the disregard for the constitution of the Republika Srpska.

Dodik says he will continue his fight in the name of the people he represents, “The will of the people will prevail, no one can break the political will of a people. I will listen to the people, because I received my mandate from the people.”

He noted that, according to the law, the mandate of the Bosnian Serb president only ends with recall or resignation; the electoral commission can only grant or confirm this mandate, it has no right to revoke it.

Dodik has taken several steps in recent months to promote the independence of Republika Srpska. In mid-March, he submitted a draft of the new constitution for the region, as well as a law on the protection of the constitutional order of Republika Srpska.

For nearly three decades, the politician has been calling for Republika Srpska to become independent and believes that Bosnia and Herzegovina is unfit to function as a state. Dodik is known for his ambitions for closer ties to both Russia and Serbia.

Hungary has been a close friend to Dodik, calling for an “end to the witch hunt” against him and also previously pushing for fast-track EU accession of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Dodik has publicly thanked Hungary for €100 million sent to Republika Srpska for the development of agriculture as well.

Western ‘interventionism’ has turned Bosnia and Herzegovina into a ‘failed state’ – Bosnian Serb leader

RT | April 2, 2025

Western interference has turned Bosnia and Herzegovina into a “failed state,” and the country now needs Russia’s help to resolve the crisis, Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik has told RT. Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska – the Serb-majority autonomous region within Bosnia and Herzegovina – arrived in Russia on Monday for talks with President Vladimir Putin.

Bosnia and Herzegovina was created under the 1995 US-brokered Dayton Peace Agreement, which ended the civil war in the former Yugoslavia. It formed a state comprised of the Bosniak-Croat Federation and Republika Srpska, with a tripartite presidency and an international overseer – the Office of the High Representative (OHR), now held by Christian Schmidt, a former German lawmaker appointed in 2021.

Dodik has long rejected the OHR’s authority, accusing it of overreach and undermining Republika Srpska’s autonomy. He was sentenced in February to a year in prison and a six-year political ban for defying the OHR. Sarajevo issued a national arrest warrant for him and is reportedly seeking Interpol warrants.

In an interview with RT on Tuesday, Dodik said the Dayton agreement, which formed his country, is no longer upheld, and that he has asked the Russian president, who he met with earlier that day, to assist him in bringing the situation to the attention of the UN Security Council (UNSC).

“[Putin] knows of the existence of foreigners that are making up laws and decisions in our country, that there are courts which abide by these decisions… and that this is not in the spirit of Dayton,” Dodik said. He added that as a permanent UNSC member and Dayton signatory, Russia is in a position to effect change.

“We talked about the need to engage in the monitoring of the UNSC. Russia is the only one from which we can expect to have an objective approach… to end international interventionism which degraded Bosnia and Herzegovina and made it into a failed state,” he added.

Commenting on the Interpol warrants, Dodik said, “we’ll see how it goes,” adding that he already has the backing of Serbia, Hungary, and now Russia. He went on to call the charges “a political failure” by Sarajevo and the OHR.

“I think they would like to see me dead, not just in prison. They can’t get the Bosnia they want, in which there is no Republika Srpska, if Milorad Dodik remains president,” he said, adding that critics will try to demonize him for meeting with Putin.

Dodik has opposed Bosnia’s NATO membership and called for closer ties with Russia. He previously suggested that Bosnia would be better off in BRICS and has pledged continued cooperation with Moscow despite Western pressure.

Russia, which does not recognize Schmidt’s legitimacy due to the lack of UNSC approval, has denounced Dodik’s conviction as “political” and based on “pseudo-law” imposed by the OHR.

After meeting with Putin, Dodik said on X that he will return to Republika Srpska on Saturday to meet with regional leaders, adding that Russia has agreed to advocate for an end to the work of international bodies in Bosnia, including the OHR.

Serbia between political destabilization and a new military front in the Balkans

By Lorenzo Maria Pacini | Strategic Culture Foundation | March 24, 2025

Bosnia’s dysfunctional political system, the result of the 1995 Dayton Accords that divided the country into two entities jointly governed by Serbs, Croats (a Catholic majority) and Muslims, with a rotating presidency under international supervision, is inexorably collapsing. In Serbia, protests against corruption and for regime change have been going on for months, and last weekend’s protests were the most impressive to date. Images of the human tide that invaded the streets of Belgrade went around the world in no time at all, but also caused a lot of confusion about the events.

In Bosnia, recent tensions have arisen from the issuance of arrest warrants by the central authorities against the president of the Republika Srpska Milorad Dodik, his prime minister and the president of the parliament. The measures stem from their refusal to comply with the directives of the “high representative” Christian Schmidt, whose appointment in 2021 by the Biden administration was not approved by the UN Security Council. Consequently, neither Dodik nor Russia recognize his authority, believing that his requests aim to reduce the autonomy of the Republika Srpska in order to favor the centralization of the Bosnian state for the political advantage of the Islamic component.

One of Schmidt’s main objectives would be to eliminate the Republika Srpska’s veto on Bosnia’s entry into NATO, which would explain the international pressure on Dodik and the attempt to remove him. Despite the differences between the Biden and Trump administrations, the latter does not seem to actively oppose this strategy. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has accused Dodik of undermining the stability of Bosnia and Herzegovina, stating that the country should not fragment; simultaneously, Dorothy Shea, the US chargé d’affaires at the UN, has expressed support for EUFOR (European Union Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina), hinting at the possibility of intervention against the leadership of Republika Srpska. Nothing new from the western Atlantic front.

In response to these unpleasant provocations, Dodik invited Rubio to a dialogue to present the Serbian point of view and made an interesting proposal: to grant American companies exclusive rights to extract rare earth minerals from the Republika Srpska, a deal with an estimated value of 100 billion dollars, which could attract the attention of the Potus, and emphasized that US policy in the Balkans is still influenced by the so-called Deep State, in particular by elements of the American embassy in Bosnia, historically hostile to Trump.

British involvement in Bosnian tensions cannot be ruled out, considering that the Russian Foreign Secret Service, the SVR, recently denounced the UK’s role in sabotaging Trump’s policy of rapprochement with Russia, almost coinciding with the accusation that Nikolai Patrushev, Putin’s advisor, made towards London, saying that he tried to destabilize the Baltic countries, hinting that he could act in a similar way in the Balkans.

Things are not much better in Serbia

The situation in Serbia is equally delicate. The country has been shaken by protests, which began after a train station incident in Novi Sad last November, fueled by discontent over corruption, with demands for accountability that could lead to a change of government. However, the protest movement is heterogeneous, including both Western-linked groups and Serbian nationalists.

Globalist liberals accuse President Aleksandr Vucic of being too pro-Russian for not having imposed sanctions on Moscow, while Serbian patriots consider him excessively pro-Western for his ambiguous positions on Kosovo, Russia and Ukraine. Vucic, for his part, claims that the protests against him are part of a Western strategy to destabilize him, and Russia itself has allegedly confirmed a supposed plot for a coup against him.

Despite accusations of Western interference, Vucic has maintained cooperation with NATO, signing a “Partnership for Peace” agreement in 2015 allowing the Alliance to transit through Serbia and in August 2024, while facing large-scale protests, he signed a three billion dollar deal with France for the supply of warplanes, raising doubts about the West’s real hostility towards him. Throughout all this, the United States continues to exert pressure on him through various channels.

The tensions in Bosnia and Serbia are not unrelated: the Western objective seems to be for Bosnia to join NATO and for Russian influence in the Balkans to be reduced. If Trump does not oppose the current policy or does not accept Dodik’s offer on rare earths, the risk of an escalation in Bosnia could increase.

Geopolitically speaking, the American doctrine of division and control continues to prevail in the Balkans, seeking to exclude any possible reunification of Bosnia and Serbia.

The only chance for the Serbs to improve their position will be close coordination between Serbia, the Republika Srpska and, if possible, Russia, to counter Western pressure and obtain the best possible result.

NATO takes advantage of the situation

Throughout all this, NATO doesn’t miss the opportunity to take advantage of the situation. The Secretary General, Mark Rutte, has declared that the actions of the Republika Srpska are unacceptable and that the United States will not offer any support to Dodik, a position also reiterated by the American Embassy in Bosnia.

EUFOR has announced that it will reinforce its contingent to deal with the growing tensions, sending reinforcements by land through the Svilaj and Bijaca passes and by air to Sarajevo airport. An excellent excuse to deploy a good number of soldiers to guard what increasingly seems to be a color revolution involving two countries.

Despite growing international pressure, the Republika Srpska can count not only on the support of Moscow and Belgrade, but also on the diplomatic support of Budapest and Bratislava, who have expressed their support for a peaceful resolution of the situation, avoiding participating in veiled military threats.

On March 10, the Chief of Staff of the Serbian Armed Forces, Milan Mojsilović, met his Hungarian counterpart, Gábor Böröndi, in Belgrade and they discussed regional and global security, as well as joint military activities aimed at strengthening stability in the area. The intensity of bilateral military cooperation was reaffirmed, with the intention of expanding it further. Particular attention was paid to joint operations between the land and air components of the two armies, as well as to the contribution of Hungarian forces to the international security mission in Kosovo and Metohija.

It seems clear that the only way for NATO to put an end to Serbian-Bosnian sovereignty is to trigger a new internal conflict, using local armed groups along the lines of what happened in Syria, or a sort of Maidan based on the 2014 Ukrainian model.

The military risk fueled by KFOR

The Kosovo Force (KFOR) is an international mission led by NATO, established in 1999 with the aim of ensuring security and stability in Kosovo, in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244.

At the beginning of the operation, it had over 50,000 soldiers from 20 NATO member countries and partner nations. Over time, the presence has been reduced. As of March 2022, KFOR consisted of 3,770 soldiers from 28 contributing countries.

To give an idea of the type of deployment, consider that there are:

– Regional Command West (RC-W): unit based at “Villaggio Italia” near the city of Pec/Peja, currently consisting of the 62nd “Sicilia” Infantry Regiment of the “Aosta” Brigade. RC-W also includes military personnel from Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, North Macedonia, Poland, Turkey, Austria, Moldova and Switzerland.

Multinational Specialized Unit (MSU): located in Pristina and commanded by Colonel Massimo Rosati of the Carabinieri, this highly specialized unit of the Carabinieri has been present in Kosovo since the beginning of the mission in 1999. The regiment has been employed mainly in the northern part of the country, characterized by a strong ethnic Serbian population, particularly in the city of Mitrovica.

The main operational activities of KFOR include:

– Patrolling and maintaining a presence in Kosovo through regular patrols;

The activity of the Liaison Monitoring Teams (LMT), which have the task of ensuring continuous contact with the local population, government institutions, national and international organizations, political parties and representatives of the different ethnic groups and religions present in the territory. The objective is to acquire information useful to the KFOR command for the carrying out of the mission;

– Support for local institutions, in an attempt not to give in to Serbia’s demands.

These are forces that are deployed and ready to intervene. This is a detail that must be taken into consideration. NATO is not neglecting the strategic importance of that key area of the Balkans.

With their backs to the wall, the governments of Serbia and Republika Srpska don’t have many options: they will soon have to face difficult choices, which could radically change the face of the Balkans.

In short, we are once again at risk of seeing the Balkans explode, as happened just over 100 years ago. Who will be responsible for the explosion this time?

Orban blasts conviction of Bosnian Serb leader

RT | February 26, 2025

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has condemned the conviction of Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik by a court in Sarajevo, describing it as a “political witch hunt” and a misuse of the legal system against a democratically elected official. Such moves are detrimental to the stability of the Western Balkans, he warned.

A Bosnian court sentenced Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska, to one year in prison on Wednesday for obstructing decisions made by Bosnia’s constitutional court and defying the authority of international envoy Christian Schmidt, who oversees the implementation of the 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement that concluded the Bosnian war. The court also barred Dodik from holding political office for six years.

“The political witch hunt against President @MiloradDodik is a sad example of the weaponization of the legal system aimed at a democratically elected leader,” Orban wrote on X in response to the court’s ruling.

“If we want to safeguard stability in the Western Balkans, this is not the way forward!”

Dodik did not attend the sentencing but addressed supporters in Banja Luka afterward, denouncing the ruling as politically motivated and pledging to implement “radical measures.” He warned that the conviction could deal a “death blow to Bosnia and Herzegovina” and suggested the possibility of Republika Srpska’s secession.

In a post on his official X account, Dodik announced plans for the Republika Srpska National Assembly to reject the court’s decision and prohibit the enforcement of any rulings from Bosnia’s state judiciary within its territory. Republika Srpska would obstruct the operations of Bosnia’s central government and police within its jurisdiction, he declared.

Dodik has two weeks to appeal the verdict. Legal experts indicate that the sentence will become final once the appeals process is exhausted.

Following the verdict, Dodik communicated with Orban and Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, expressing gratitude for their support. Vucic has convened an emergency meeting of Serbia’s National Security Council to discuss the implications of Dodik’s sentence and is expected to visit Republika Srpska within the next 24 hours.

Dodik is known for his opposition to NATO and has resisted Bosnia’s accession to the US-led military bloc. He has also opposed Western sanctions against Russia related to the Ukraine conflict.

Biden has pledged that ‘America is back.’ But as peace shatters in the Balkans, does that mean yet more US misadventures?

KFOR forces patrol near the border crossing between Kosovo and Serbia in Jarinje, Kosovo, October 2, 2021. © REUTERS / Laura Hasani; Inset © REUTERS / Evelyn Hockstein

By Julian Fisher | RT | October 24, 2021

With warnings that fresh tensions between Serbia and Kosovo could unravel the decades-old peace deal that put an end to bloody fighting in the Balkans after the breakup of Yugoslavia, the US is increasingly split on what to do.

Earlier this month, the SOHO forum in New York City hosted a debate between Scott Horton, long-time libertarian and anti-war radio host, and Bill Kristol, the neoconservative thinker and one of the ideological architects of America’s post-9/11 world order. The subject of the debate was US interventionism, its merits and historical record.

Predictably, Kristol offered vague niceties that attempt to recast America’s legacy as that of the “benevolent global hegemony”, a term which he himself coined in 1996 when describing the country’s role in the world. Reflecting on the wars in Iraq, Kristol simultaneously said that America “didn’t push democracy enough” and also “may have been too ambitious.” In short, he acknowledged mistakes were made, which is an admission that would have been unthinkable only a few years ago, and yet still falls short of accountability.

However, whereas American actions in the Middle East leave a lot to be desired for Kristol, he insists that the US intervention in the Yugoslav Wars during the 1990s was a success. As he put it, the Balkans was “one case of a war that was worth it and that I think had pretty good consequences.” As if on cue, the Balkan pot is beginning to boil once again.

An unresolved conflict

Kosovo has been a potential tinderbox in Southern Europe ever since the end of the war of 1998/1999. A recent row with Serbia, from which it unilaterally declared independence, has led to a new escalation in tensions.

Beginning in September 2021, Serbs living in Kosovo launched protests against authorities hassling travelers who enter the territory with Serbian-issued license plates, prompting a mobilization of armed Kosovo police forces, roadblocks, and traffic jams near the border. Two vehicle registration offices were vandalized.

The EU mediated a temporary fix in September that involves covering up national insignia on license plates with stickers, until a special working group in Brussels determines a more permanent solution sometime within the next six months. Whether this will be sufficient in bringing about immediate calm remains to be seen, however. Since then, further clashes have erupted between police and protesters near Mitrovica.

Russia’s Foreign Ministry has condemned the use of violence by Kosovo police against ethnic Serbs. Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov met with Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic in mid-October, calling for talks between Pristina and Belgrade and a diplomatic solution to be respected by all sides.

As the situation heated up, NATO quickly ramped up patrols throughout Kosovo, including the North. “KFOR [Kosovo Force] will maintain a temporary robust and agile presence in the area,” the US-led military bloc said in an official statement earlier this month, intended to support the implementation of the EU-brokered solution. Last week, Kosovo’s minister of defense, Armend Mehaj, flew to Washington to meet with Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Dr. Colin Kahl at the Pentagon. The subject of the discussions was “bilateral security cooperation priorities”.

These moves are only the latest instance of US-led posturing in Kosovo. It was with American support that Kosovo launched its campaign for international recognition in 2008. Many major countries, representing most of the world’s population — including Russia, China, and India — have not recognized it as a sovereign state. Kosovo’s persistent claim to independence is what makes an issue as seemingly benign as license plates a question of war and peace.

In the background is still the 1999 Kosovo War, which was the site of NATO’s infamous bombing campaign against Serbia that led to the deaths of at least 489 civilians, according to Human Rights Watch. In April of 1999, NATO deliberately targeted Serbia’s Radio Television station, killing 16 civilians, according to Amnesty International. At one point, the US “mistakenly” bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, killing three and wounding some 20 more, in what turned out to be the only target picked by the CIA over the course of the war.

To this day, the US maintains a military base, Camp Bondsteel, near Urosevac, Kosovo, as part of the international Kosovo Force (KFOR).

Two states in one

To the west, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has also reappeared in international news coverage. Against the backdrop of the EU’s Western Balkan Summit in early October, the Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik said last week that the parliament of the Serb Republic, one of two entities that together make up BiH, would soon vote to undo some of BiH’s state institutions. He included the military, the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council (HJPC) and the tax administration. These and others were established after the signing of the 1995 Dayton Peace accords and are not enshrined in the constitution.

Dodik wants an independent Serb Republic without compromising the territorial integrity of BiH, and he claims he has the support of seven EU member states, though he has not said which ones.

The genesis of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s recent headache is an amendment to the Criminal Code that makes various forms of inflammatory speech a punishable offense. The law was enacted in July of this year by the Office of the High Representative, an international “viceroy” with the power to impose binding decisions and remove public officials.

Russia has maintained that this appointed position is outdated, with a statement from the Foreign Ministry saying it was high time to “scale down the institute of foreign oversight over Bosnia-Herzegovina, which only creates problems and undermines peace and stability in that country.” Moscow also remains critical of attempts to integrate the country into NATO, insisting there is no consensus among the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina when it comes to joining the US-led bloc.

Playing to a different tune, already last month Washington tried to reprimand Dodik for his “secessionist rhetoric”. In a meeting just a few weeks ago, US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Gabriel Escobar warned of “nothing but isolation and economic despair” for the people of the Serb Republic. According to a transcript that Dodik shared with the press, he told Escobar that he doesn’t “give a damn about sanctions,” adding, “I’ve known that before. If you want to talk to me, don’t threaten me.”

In the US, various Balkan-American organizations have released a joint statement calling on Congress and the Biden administration “to immediately initiate steps to rebuff the attempts by the government of Serbia to unravel the region’s peace and security”. Citing both aforementioned developments in Kosovo and the Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the statement demands a reinvigoration of “NATO enlargement as a priority for the region.” It suggests that what’s at stake in the Balkans is America’s legacy: “America invested too much of its own resources into this region to allow revanchist actors to decimate nearly a quarter century of progress.”

However, what does America investing its resources actually look like? In early 1992, before the war that scarred Bosnia and Herzegovina, all parties involved had already come to an agreement, the Carrington–Cutileiro plan, to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina into cantons along Serb, Croat, and Bosniak lines.

At the last minute, however, the then-US ambassador to Yugoslavia, Warren Zimmermann, met with the leader of the Bosniak majority, Alija Izetbegovic, in Sarajevo, reportedly promising him full recognition of a single Bosnia and Herzegovina. Izetbegovic promptly withdrew his signature from the partition agreement, and shortly thereafter the US and its European allies recognized Izetbegovic’s state. War ensued a month later, in April 1992. The US eventually worked its way back to new partition negotiations that echoed the talks held prior.

As the New York Times reported in 1993, “tens of thousands of deaths later, the United States is urging the leaders of the three Bosnian factions to accept a partition agreement similar to the one Washington opposed in 1992.”

Zimmermann is quoted as saying at the time that “Our hope was the Serbs would hold off if it was clear Bosnia had the recognition of Western countries. It turned out we were wrong.”

Returning to the Horton-Kristol debate from earlier, Horton cited America’s underhanded opposition to the Carrington-Cutileiro plan, and the devastating consequences, as a case in point of US interventions impeding, rather than promoting, peace and stability.

President Joe Biden declared at the start of his administration that “America is back.” Taking a look at the history of US interventions, this could spell trouble for the Balkans.

Julian Fisher is a policy analyst at the Russian Public Affairs Committee (Ru-PAC). He writes about Russia-U.S. relations, American foreign policy, and national security