The New Scientist Misses the Science on ‘Sinking Pacific Islands’

By Anthony Watts | Climate Realism | January 16, 2026

The New Scientist (NS) recently published “The Pacific Islanders fighting to save their homes from catastrophe” by Katie McQue and Sean Gallagher. The article claims that small Pacific island nations face an existential threat from rising seas and intensifying storms driven by climate change, with displacement already underway and submergence looming. This article is factually false and unsupported by real-world data. The piece relies on emotive anecdotes and dire projections while ignoring a substantial body of empirical research showing that many low-lying islands and atolls are stable or growing, keeping pace with sea-level rise rather than succumbing to it.

The article asserts that “rising seas are anything but a distant projection,” that high tides now regularly inundate areas that “used to stay dry,” and that island nations such as Tuvalu could be “almost completely submerged at high tide by the end of the century.” It further suggests that climate-driven sea-level rise is already forcing migration and poses an existential risk. These claims are presented as settled science, yet New Scientist fails to engage with the very studies that have directly measured island change over time.

Actual surveys of island nations tell a very different story. As summarized in Climate at a Glance’s evidence-based review “Islands and Sea Level Rise,” dozens of peer-reviewed studies using aerial photography, satellite imagery, and on-the-ground surveys show that the majority of low-lying coral islands have remained stable or increased in land area over recent decades. Research on atolls in the Pacific and Indian Oceans finds that sediment transport, reef dynamics, and natural island-building processes allow islands to adjust to gradual sea-level rise. In other words, these islands are not passive sand piles waiting to drown; they are dynamic landforms.

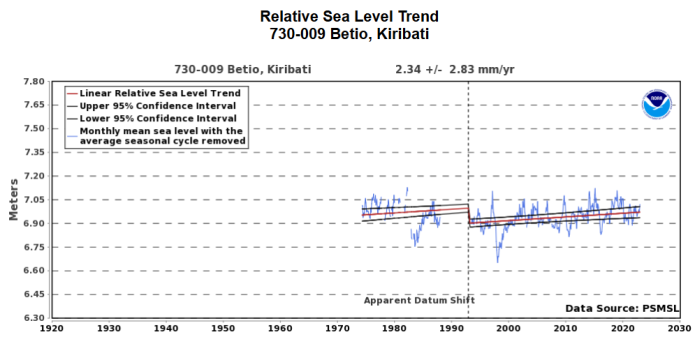

This is not a fringe view. Climate Realism has repeatedly documented how media outlets ignore these findings, including in its coverage collected under island and sea-level rise reporting, where studies showing island growth in places like Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands, and Kiribati are contrasted with alarmist headlines predicting imminent disappearance. Those empirical studies directly contradict New Scientist’s framing of inevitability and catastrophe. Further, sea level rise data from NOAA on the island of Kirbati is quite modest, just 0.77 feet per century.

Relative sea level trend is 2.34 millimeters/year with a 95% confidence interval of +/- 2.83 mm/yr based on monthly mean data from 1974 to 2022 which is equivalent to a change of 0.77 feet in 100 years

Equally telling is what is happening on the ground. Island nations supposedly facing near-term sea level submergence are investing heavily in long-term infrastructure. Tuvalu, the Maldives, Fiji, and other Pacific and Indian Ocean nations are expanding airports, reclaiming land, and approving major hotel and resort developments. These are capital-intensive projects with planning horizons measured in decades, not emergency stopgaps for populations about to flee. Governments and investors with real money at stake do not behave this way if these countries are about to vanish beneath the waves.

NS also conflates local flooding, erosion, and freshwater management problems with global sea-level rise. High tides washing into low areas, saltwater intrusion into wells, and coastal erosion are often driven by local factors such as land use, groundwater extraction, reef damage, and poor coastal management. Treating every such problem as proof of climate catastrophe is a classic case of confusing site-specific issues with global trends.

Perhaps most damning is what NS does not do.

It does not cite the extensive body of peer-reviewed literature documenting island stability and growth. It does not explain why measured island area changes contradict its narrative. It does not ask why nations allegedly facing “existential” risk are expanding infrastructure rather than abandoning it. Instead, it relies on selective anecdotes, speculative end-of-century projections, and emotionally charged language to imply a settled scientific conclusion that the data do not support.

If the New Scientist were actually doing science rather than regurgitating rhetoric, this article would not exist in its current form. A serious treatment would grapple with the observational record showing that many island nations are keeping up with sea-level rise, not disappearing beneath it. By failing to cite that science and by presenting a one-sided story of inevitable catastrophe, the New Scientist misleads readers and does a disservice to both the public and the people living on these islands, whose real challenges deserve honest, evidence-based discussion—not recycled counterfactual climate alarmism.

New Scientist jumps the climate gun

Is the Pacific Jet Stream drifting poleward?

By Dr David Whitehouse | NetZero Watch | September 26, 2024

This week’s prize for jumping the climate gun goes to New Scientist, twice.

Firstly, it tells us that low sea ice levels in Antarctica signal a permanent shift. This, they say, because for the second year in a row Antarctic sea ice has reached near-record low levels, “initiating concern that climate change has initiated a ‘regime shift’ in the amount of ice that forms in the Southern Ocean each year.”

Sorry New Scientist, but two years does not a trend make. Looking at the data, 2023 was indeed a record low and 2024 slightly above that, but if you look at previous years, especially the 2011–2020 average, you will see no trend, just confirmation that 2023 and 2024 are outliers. Much more data than the past two years will be required to signal a permanent regime change.

Their second example of spurious trend-setting concerns the questions of if there is a long-term poleward shift in the jet stream, and if it might be the result of global warming. The jet stream is powered by the Earth’s rotation and by temperature differences between the tropics and higher latitudes. Its poleward drift is a prediction of some climate models.

According to New Scientist, a new analysis indicates that the Pacific Jet Stream has started its poleward drift, moving at 30–80 km a decade. The problem with this research, which is clearly stated in the paper, is that the Jet Stream’s natural bounds of variability are not known, and despite the data going back several decades, if the past ten years are excluded from the analysis then no poleward trend is seen. The researchers say it’s going to take to the end of this century to be sure of any systematic Pacific Jet Stream drift.

Over the past few months, something very unusual has been happening in the equatorial Atlantic Ocean. Temperatures have declined at their fastest for over 40 years. Climate scientists are at loss to explain it, as the usual culprit – trade winds – haven’t developed as expected.

It has been called an “Atlantic Niña.” Along with the developing La Niña in the Pacific, it is expected to reduce global temperatures. It’s a puzzle, as the equatorial Atlantic was hot throughout 2023 – in fact the warmest for decades. Again the reaction by some has been alarmist, fearing that the climate system has gone off the rails, but my initial response is to wait and see, as it is probably an example of misunderstanding of natural variability.