On Tuesday 5 March, at the age of 58, Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez lost his almost two-year battle with cancer and passed away. Within seconds of the news being announced, the wheels of the global media bandwagon went into overdrive, with largely unsurprising results, in both the US and British media. At the most distasteful end of the spectrum was the headline in the New York Post, the paper with the 7th highest circulation in the US, that read ‘Off Hugo! Venezuela bully Chavez is dead’.

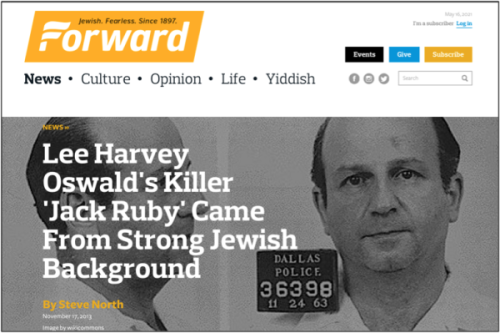

New York Post Cover on Chávez

Other US media followed closely behind. ‘Death of a Demagogue’ ran a headline on the website of Time, the world’s biggest selling weekly news magazine. These and other US media reaction were included in a piece by the US media watchdog Fair and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) that also examined the distorted, often hysterical, US media coverage of Chávez during his presidency. It’s worth recalling that following the 2002 US-supported coup that briefly removed Chavez from the presidency the New York Times declared that Chavez’s “resignation” meant that “Venezuelan democracy is no longer threatened by a would-be dictator.”

Following Chávez’s death, the antipathy towards a president that had so vehemently challenged the actions and interests of the United States was also evident in the British media. Rightwing outlets displayed the usual cynical disdain that had characterised their reporting of Chávez’s presidency, although Nicolas Maduro, Chávez’s former vice-president, the current interim president and the government’s candidate for the April 14th presidential election, was also now in the firing line. In the UK’s biggest selling broadsheet, the rightwing Daily Telegraph, its chief foreign correspondent David Blair described Maduro’s role as foreign minister under Chavez in the following terms: “Mr Maduro was the obedient enforcer of his master’s highly personal foreign policy”. For Blair, Maduro, rather than responsibly representing his government’s foreign policy, was “a loyal purveyor of ‘Chavismo’ around the world”.

The ‘liberal’ left in Britain

Britain’s liberal-left media also offered a timely reminder of where their loyalties lay in relation to Chavez, whose democratic mandate included presiding over 15 national elections since he took office in February 1999, a greater number of elections than were held during the previous 40 years in Venezuela. In a remarkable editorial, The Independent newspaper opined:

“Mr Chavez was no run-of-the-mill dictator. His offences were far from the excesses of a Colonel Gaddafi, say. What he was, more than anything, was an illusionist – a showman who used his prodigious powers of persuasion to present a corrupt autocracy fuelled by petrodollars as a socialist utopia in the making. The show now over, he leaves a hollowed-out country crippled by poverty, violence and crime. So much for the revolution.”

This from a newspaper that in June 2009, following a military coup that overthrew the democratically elected government of President Manuel Zelaya in Honduras, ran an editorial that included the following:

“The ousting of the Honduran President Manuel Zelaya by the country’s military at the weekend has been condemned by many members of the international community as an affront to democracy. But despite a natural distaste for any military coup, it is possible that the army might have actually done Honduran democracy a service.”

The Independent’s competitor in the UK’s liberal-left newspaper market, The Guardian, showed a similarly hostile stance towards Chavez during his presidency. In a piece on the New Left Project website examining the critical UK media coverage of Chavez following his death, Josh Watts noted how the anti-Chavez bias of Rory Carroll, a Guardian journalist and its former Latin America correspondent, “has been extensively documented”. As Samuel Grove noted in a damming 2011 article, Carroll’s Latin America coverage “has attracted widespread criticism for its selectivity and double standards, brazen anti-left bias, and above all slavish loyalty to Western interests”. There is now surely a book’s worth of material exposing Carroll’s distorted Venezuela coverage.

Carroll has managed to take his agenda beyond the confines of The Guardian. For example, in an Al Jazeera English debate on the continued demonisation of Chavez by the Western media that took place three days after Chavez’s death, Carroll repeatedly tried to present Venezuela under Chavez as an economic failure. He repeated this line of attack in a BBC 3 radio interview in late February, where he accused the Chavez government of being responsible for “decay, ruin, waste” in relation to the economy. Contrast this with the rigorous reports on the socio-economic changes under the Chavez presidency by the Washington-based think tank, the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), which completely undermine Carroll’s narrative of economic failure.

This fact-based approach to appraising elements of the Chavez legacy has not been lost on The Guardian’s associate editor Seumas Milne, who referenced CEPR’s latest report when he tweeted: “Media claims #Chavez ruined #Venezuela‘s economy absurd: here are the facts on growth, unemployment, poverty http://bit.ly/13Nnwno @ceprdc”

It was precisely these socio-economic gains, especially for those in the low-income neighbourhoods known as barrios that encircle Caracas and other Venezuelan cities and who formed Chávez’s support base, that lay behind his popularity and his repeated electoral victories.

Focus on denigrating the individual

Rather than try to explain Chávez’s appeal to large sectors of the Venezuelan population or understand the process of radical change underway in the country, the West’s media class preferred to focus almost entirely on the figure of Chávez. It was precisely this narrative that was so effective in discrediting the Venezuelan process through concealing the role of collective agency, silencing the people from below, and rendering them insignificant. While the mainstream media routinely ignores the voices of the government’s grassroots supporters, they have been instrumental in driving the Venezuelan process forward and should be at the centre of the story.

Thus, when we contrast Chávez’s popularity at home with the open hostility with which Western political elites viewed him, we’re left questioning the motivation behind the anti-Chávez mass media campaign that has systematically misrepresented events in Venezuela.

John Pilger is right when he writes:

“Never has a country, its people, its politics, its leader, its myths and truths been so misreported and lied about as Venezuela.”

Even though Chávez is dead, his vilification by the US and UK media is alive and kicking.

Pablo Navarrete is a LAB correspondent and a PHD student at Bradford University in the UK, researching the political economy of the Chavez presidency. He is also the director of the documentary ‘Inside the Revolution: A Journey into the Heart of Venezuela’ (Alborada Films, 2009). You can watch the documentary online here.

March 14, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Deception, Mainstream Media, Warmongering | Chavez, Hugo Chávez, Independent, New York Times, Nicolás Maduro, Rory Carroll, United States, Venezuela |

Leave a comment

Venezuela’s acting President Nicolas Maduro says ‘far-right’ figures in the United States have plotted to assassinate opposition leader Henrique Capriles.

Maduro gave the announcement in a televised speech on Wednesday.

“We have detected plans by the far-right, linked to the groups of (former Bush administration officials) Roger Noriega and Otto Reich, to make an attempt against the opposition presidential candidate,” Maduro stated.

According to Venezuela’s opposition party, Capriles did not register his candidacy in person on March 11 over information he had received about being the target of a planned attack. Aides to Capriles delivered the registration papers instead of him.

Venezuela is preparing for presidential election on April 14 to vote for a replacement for late President Hugo Chavez.

On March 8, Maduro was sworn in as acting president, pledging to push ahead the former leader’s agenda.

Before Maduro’s inauguration, over 30 world leaders paid tribute to Chavez at a high-profile funeral.

Chavez passed away on March 5 at the age of 58 after a two-year battle with cancer.

The late Venezuelan leader started the Bolivarian Revolution to establish popular democracy and economic independence and to equitably distribute wealth in Latin America.

Chavez was one of the key players in the progressive movement that has swept across Latin America over the past few years.

March 14, 2013

Posted by aletho |

False Flag Terrorism, Timeless or most popular | Henrique Capriles Radonski, Otto Reich, Roger Noriega, United States, Venezuela |

Leave a comment

Merida – Globovision, an opposition news television station, announced yesterday that it has accepted a buyout offer, to be carried out after the 14 April presidential elections.

Various Globovision spokespeople attributed the sale to supposed operational and profitability issues, on which they blamed the Venezuelan government.

According to Globovision’s majority owner, Guillermo Zuloaga, the group buying the channel is headed by Juan Domingo Cordero, who also runs an insurance company, Vitalicia. According to El Nacional, Cordero has also been on the executive boards of the stock exchange, another insurance company, and a small bank.

“We are economically unviable, because our revenues no longer cover our cash needs… we are politically unfeasible, because we are in a totally polarised country and against a powerful government that wants to see us fail,” Zuloaga said in a statement.

Further, the host of Globovision’s program ‘Alo Ciudadano’ – a program that aimed to counter Chavez’s Sunday show ‘Alo Presidente’, Leopoldo Castillo, discussed the sale yesterday. He claimed the reasons for it include requiring technology, being judicially unviable, the priority of “saving the workers” and “many difficult years, it has become more and more difficult to satisfy the needs … of the personnel of Globovision”.

So far, the English language private press has reported the news of the sale as an issue of “press freedom”, with Associated Press referring to the government’s so called “campaign to financially strangle the broadcaster through regulatory pressure… the announcement… is a crushing blow to press freedom”.

Jose Vivanco, director of Human Rights Watch, also said the news was part of a “disturbing trend… the government of Venezuela has created an environment in which journalists weigh the consequences of what they say for fear of suffering reprisals”. Human Rights Watch has consistently attacked the Bolivarian government, misrepresented its human rights situation, and declined to criticise the 2002 short lived coup against then president Hugo Chavez.

However Zuloaga’s own statement says, “Since we began [20 years ago] we have had problems with the government, which is natural for an information channel. With the last government of Rafael Caldera… they didn’t want to give us access to official sources”.

He then mentions the “attacks getting stronger” under the current government, and that last year, he decided to “do everything in our power…to make sure the opposition won the [presidential] elections in October…but the opposition lost”.

Private press are reporting that the buyer, Cordero, is “friendly” with some government officials, but so far has offered no concrete examples or proof of this, only citing anonymous “sources”.

According to Entorno Inteligente, Cordero has promised to improve the quality of news, and maintain the channel’s audience and workers. Zuloaga says in his statement that he has known Cordero “for years” and “he is a successful man in the financial world”.

Globovision’s public broadcast licence is up for renewal in 2 years. The Zuloaga family owns 80% of Globovision, but Zuloaga has been living overseas since 2010 when courts put out an arrest warrant for him for conspiracy and general usury over irregularities in his car dealership.

Journalists for the Truth respond

“The announced sale of Globovision is the strongest proof of the upcoming defeat of the candidate for the bourgeoisie [and the opposition], Henrique Capriles, in the 14 April [presidential] elections,” said Marco Hernandez, president of the Venezuelan NGO, Journalists for the Truth.

He asserted that the timing of the announcement was convenient, arguing that “its false that the channel is economically nonviable… it’s enough to look at their publicity income… with net earnings of BsF 11 million (US $1.75 million) … and Globovision’s workers have the highest salaries in the field and they have the best technology in Venezuela”.

“What’s happening is the owners of [Globovision] are only thinking about their own interests as capitalists… not in the journalists who they use like cannon fodder… they take for granted that Capriles will lose… and knowing that their licence doesn’t deserve renewing… they are selling their channel because it doesn’t have any value without the concession granted to them by the state,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez pointed out that Zuloaga is a “fugitive” and that in his statement he had admitted he was an “enemy of the government” and therefore his channel wasn’t “an independent news channel” as it claimed to be.

“The truth is that it is a propaganda trench for the Venezuelan and international oligarchy opposed to the changes promoted by Chavez, something that is provable by analysing their programming,” Hernandez said.

“Their programming is so extreme and manipulative of the truth that it has been the object of innumerable denunciations by Consumer Organisations (OUU), and the opening of eight administrative proceedings against it, and a sanction by [public communication body] Conatel,” Hernandez added.

Last June Globovision paid a fine of Bs 9.3 million (US $1.5 million), eight months after the fine was first emitted by Contatel. The station only paid the fine after the Supreme Court ordered an embargo on part of its assets, to force compliance.

Conatel issued the fine after determining that Globovision had broken articles 27 and 29 of the Law of Social Responsibility in Radio and Television during its coverage of the Rodeo prison hostage situation in June 2011. The station played interviews of distraught prison mothers 269 times over four days and added the sound of gunfire to the reports.

March 13, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Deception, Mainstream Media, Warmongering | Associated Press, Globovision, Henrique Capriles Radonski, Marco Hernandez, Rafael Caldera, Venezuela, Zuloaga |

Leave a comment

On the occasion of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez’s death last week, much of the international media responded in typical fashion, by painting the Chavez administration much as they painted it when Chavez was alive—as an autocratic regime led by a foolish tyrant who mismanaged the country and squandered its oil wealth.

They showed little mercy for the larger-than-life leader, so beloved by the majority in his country, and by millions around the world, giving the impression that Hugo Chavez got almost everything wrong, and did virtually nothing right.

Many of the criticisms have an element of truth to them, as many problems persist in Venezuela. And the press made sure to highlight these problems as evidence of Chavez’s failure, making it sound as if any sensible leader or government in Chavez’s position could have resolved them. But what showed through more than anything in these anti-Chavez tirades was a very revealing, almost embarrassing, misunderstanding of Venezuela’s principal economic and social issues.

“It’s a pity no one took 20 minutes to explain macroeconomics to him,” writes Rory Carroll in an op-ed in the New York Times that claims Chavez was “an awful manager” who destroyed Venezuela. Carroll slams Chavez for everything from failing to fix up the presidential palace, to spending too much on education and health, to not investing enough in infrastructure.

As The Guardian’s correspondent in Venezuela since 2006, Carroll apparently had seen enough to conclude that Chavez had “left Venezuela a ruin”. Yet one wonders if he ever managed to talk to the millions of Venezuelans—those who packed the streets to mourn the president’s death last week—who feel the country has been forever transformed.

For literally days on end, non-stop, all day and all night, people filed through the building where Chavez’s body was displayed to pay their final respects. A line stretched for miles outside, as people waited several days, eating and sleeping in the line, just to see their president one last time. This immense outpouring of emotion is very hard to square with the image Carroll gives us.

It might be an exaggeration to say Chavez transformed the country—though many things were deeply changed—but one doesn’t have to be an expert to know that Venezuela’s problems are more complicated than one man and his personality quirks.

The Economist tells us that Chavez was a “narcissist” who was “reckless” with his country’s economy and who “squandered an extraordinary opportunity”. We are told Chavez could have used the country’s oil wealth to “equip [Venezuela] with world-class infrastructure and to provide the best education and health services money can buy”. But due to mismanagement, “the economy became ever more dependent on oil”. Carroll echoes this, blaming Chavez for a “withering” private sector, and decaying infrastructure.

But apparently these self-proclaimed experts have never taken even the most cursory look at Venezuelan history. Had they done so, they would know that since Venezuela’s oil wealth was first discovered nearly a century ago, no government has ever been able to do what they claim should have been accomplished by the Chavez government.

Past governments have invested the country’s oil wealth in infrastructure, industry, and development projects—though never as much as Chavez—yet not one of them managed to break dependence on oil, diversify the economy, create a flourishing private sector, or build adequate health and education services. Was it because they were all reckless narcissists? Or do these problems perhaps have an explanation that goes deeper than the president’s personal style?

Of course, the truth is much more complex than what the Chavez haters would like to admit. It is true that Chavez did not provide solutions to many of Venezuela’s problems, and that some problems even got worse, but contrary to the media claims, he probably did better than any previous government in Venezuelan history.

One gets the opposite impression from much of the international media. Take a look at the following paragraph from last week’s article in the The Economist:

Behind the propaganda, the Bolivarian revolution was a corrupt, mismanaged affair. The economy became ever more dependent on oil and imports. State takeovers of farms cut agricultural output. Controls of prices and foreign exchange could not prevent persistent inflation and engendered shortages of staple goods. Infrastructure crumbled: most of the country has suffered frequent power cuts for years. Hospitals rotted: even many of the missions languished. Crime soared: Caracas is one of the world’s most violent capitals. Venezuela has become a conduit for the drug trade, with the involvement of segments of the security forces.

Amazingly, almost every sentence in the paragraph is false. Agricultural output did not drop, but rather grew by 2 to 3 percent per year, and grain production, which was the government’s major focus, grew by 140 percent. Inflation was considerably lower under Chavez than the previous two governments. Food shortages and power cuts were caused by the explosion in consumption among the poor, not a fall in production.

Both electricity production and food production have increased to all time highs. Thousands of new health clinics have been built around the country. However, it is true that many hospitals remain inadequate, that crime has soared, and that Venezuela is still a conduit for the drug trade, as it shares a large border with Colombia.

The claims of increased oil dependence are also not borne out by the facts. It is true that oil as a percentage of total exports has increased, but this is largely due to the fact that oil prices have increased nearly ten-fold since Chavez came to power, making it inevitable that their value in relation to total exports would also increase.

The critics say Chavez squandered the country’s oil wealth, which he could have used to transform it into a modern state. Indeed, the oil boom left Venezuela awash in oil money, a situation that Chavez’s policies had a hand in creating, as he united OPEC and increased royalties and taxes on the oil sector, giving the state vastly more funds to work with. If only this “awful manager” knew how to administer the funds, critics say, Venezuela could have been well on its way to becoming a modern, developed nation.

But this is shortsighted. Nations do not develop on the basis of resource wealth or commodity booms. A country cannot spend its way into the first world. Rather, economic development is about systematic growth in productivity, innovation, and technical change, activities that typically fall on the shoulders of the private sector. In the developed world, it is largely the private sector that invests surpluses into new technologies and improvements in the productive process, something that does not occur in Venezuela in a systematic fashion.

Of course, critics and opponents of Chavez argue that this is also the fault of the government, that it is Chavez’s fault for not creating the right environment for private investment, and that with the “right” policies the private sector would decide to invest in the country and would produce the kind of economic development that will benefit all sectors of society. Apparently no Venezuelan government in history has been able to figure out what those “right” policies are.

But this ideology defeats itself with its own logic, for private investors in market economies don’t invest in productivity because they feel like it, or because the conditions are just as they like. They do so because they have to in order to match the competition, to survive in the market, and to avoid going out of business. In modern market economies, producers invest in improving productivity because they are compelled to do so by the market, not because they decide they want to.

The fact that much of the private sector in Venezuela has seldom been compelled to do the same only demonstrates that this economy does not function like the model market economy that these theories are based on.

Huge swaths of the nation’s agricultural land have long been dominated by large estates—the infamous latifundios—that feel very little pressure to improve productivity, and graze cattle on the nation’s best land. The commercial and industrial sectors have long been dominated by highly diversified conglomerates—the so-called grupos económicos—that control key sectors of the economy, and are rarely threatened by competition.

In other words, it goes against these critics’ whole line of reasoning to point out that what really determines whether a country is rich or poor is not commodity booms or resource wealth, but rather has to do with productivity growth—something that has seldom been a priority for much of Venezuela’s private sector.

It’s a pity that no one took 20 minutes to explain this to Rory Carroll, The Economist and others who blame all of Venezuela’s problems on Hugo Chavez, for he did more than any president in history to try to change the unproductive logic of the private sector.

More than 3.6 million hectares of unproductive land were expropriated and redistributed to over 170,000 small producers—far more than the entire 40 years of pre-Chavez land reform. Major sectors of the economy were nationalized, and state companies expanded, in an attempt to improve production, raise investment, and remove bottlenecks. Massive investments were made in agriculture and industry—far more than under previous governments—in an attempt to spur their growth.

Many of these attempts were failures. The growing state sector often allowed for inefficiency and corruption. Chavez’s solutions to the country’s economic and social issues were not always the correct ones.

But the point is that Venezuela’s problems are quite complex and defy easy answers. Previous governments with previous oil booms also failed to resolve the country’s major problems, and did much less to help the poor, something that does not seem to interest those who want to blame everything on Chavez.

Instead of seeking to gain a better understanding of the country’s problems—to understand why they have been so intractable throughout the country’s history—the major media have preferred to vilify and condemn one man; a man who, right or wrong, spent his life trying to solve the problems that plague his country, and was undeniably dedicated to helping the poor; a man who constantly reminded his country’s poor majority that they mattered, that they were not inferior to anyone, and that they should feel proud of their national heritage. That doesn’t sound like a narcissist to me.

March 13, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Deception, Economics, Mainstream Media, Warmongering | Chavez, Guardian, Hugo Chávez, New York Times, Rory Carroll, Venezuela |

Leave a comment

Venezuela is to formally investigate suspicions late President Hugo Chavez’s was afflicted with cancer after being poisoned by foreign enemies, the government said.

Acting President Nicolas Maduro vowed to set up an inquiry into the allegation, which was first leveled by Chavez after being diagnosed with cancer in 2011. Foreign scientists will also be invited to join a government commission to investigate the claim.

“We will seek the truth,” Reuters cites Maduro as telling regional TV network Telesur late on Monday. “We have the intuition that our commander, Chavez, was poisoned by dark forces that wanted him out of the way.”

Maduro said it was too early to determine the exact root of the cancer which was discovered in Chavez’s pelvic region in June 2011, but charged that the United States had laboratories which were experienced in manufacturing diseases.

“He had a cancer that broke all norms,” the agency cites Maduro as saying. “Everything seems to indicate that they affected his health using the most advanced techniques … He had that intuition from the beginning.”

Chavez reportedly underwent four surgeries in Cuba, before dying of respiratory failure after the cancer metastasized in in his lungs.

Maduro compared the conspiracy surrounding Chavez’s death to allegations that Israeli agents poisoned Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat to death in 2004.

In December 2011, Chavez speculated that the United States could be infecting the regions leaders with cancer after Argentine President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner was diagnosed with thyroid cancer.

“I don’t want to make any reckless accusations,” Chavez said before asking:

“Would it be strange if [the United States] had developed a technology to induce cancer, and for no one to know it?” Maduro repeated the accusation last week on the eve of Chavez’s death.

“Behind all of [the plots] are the enemies of the fatherland,” he said on state television before announcing the expulsion of two US Air Force officials for spying on the military and plotting to destabilize the country.

Venezuela’s opposition has lambasted the claim as another Chavez-style conspiracy theory intended to distract people from real issues gripping the country in the run up to the snap presidential election called for April 14.

As Tuesday marked the last day of official mourning for Chavez, ceremonies are likely to continue, fueling claims by the opposition that the government is exploiting Chavez’s death to hold onto power.

While launching his candidacy on Monday, Maduro began his speech with a recording of Chavez singing the national anthem, sending many of his supporters into tears.

The pro-business state governor Henrique Capriles, who is running for the opposition’s Democratic Unity coalition, was quick to remind both his supporters and detractors that the charismatic socialist reformer Chavez was not his opponent.

“[Maduro] is not Chávez and you all know it,” The Christian Science Monitor quotes him as saying while announcing his candidacy on Sunday.

“President Chávez is no longer here.” Maduro, a former bus driver and Chavez’s handpicked successor, has attempted to deflect criticism that he lacks the former president’s rhetorical flair by painting himself as a working class hero.

“I’m a man of the street. … I’m not Chávez,” he said Sunday.

“I’m interim president, commander of the armed forces and presidential candidate because this is what Chávez decided and I’m following his orders.” Polls taken before Chavez’s death gave Maduro a 10 point lead over Capriles, who lost to Chavez in last October’s presidential poll.

March 13, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Timeless or most popular | Chavez, Hugo Chávez, Maduro, Nicolás Maduro, United States, Venezuela |

Leave a comment

Outside of Venezuela and Latin America, there was no greater outpouring of support and sympathy for Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez than in the Arab world.

Comparisons to the great Egyptian president Gamal Abdul-Nasser began immediately. Many even declared Chavez himself an Arab based on his anti-imperialist policies and support for Palestinian liberation. Political commentators, at least those not on the Saudi and Qatari payrolls, emphasized his public support for Palestinian rights and Iran’s right to pursue a peaceful nuclear program, as well as his opposition to the wars on Iraq, Libya, and most recently the proxy war on Syria.

It’s not difficult to understand why Chavez enjoyed such support and admiration among the Arab public. Chavez stood in stark contrast to the politically impotent, petty tyrants that rule the Arab world. He spent 14 years as president of Venezuela and consistently won clear majorities of the vote in free and fair elections.

During this period Arabs watched him defy the American empire as semi-literate oil-Sheikhs and brutal dictators groveled in front of the latest US secretary of state. They heard Chavez condemn the war on Iraq as Gulf Cooperation Council royals did sword dances with George W. Bush.

Arabs remembered Chavez’s condemnations of Israel’s 2006 onslaught of Lebanon, when Arab regimes were quietly, and some not so quietly, supporting Israel’s bid to destroy the resistance in Lebanon. Arabs watched Chavez’s famous speech on Gaza when Hosni Mubarak, along with Israel, was enforcing a siege on 1.5 million Palestinians. They also remember that it was Chavez who expelled the Israeli Ambassador to Venezuela in protest of Israel’s 2008 massacre in Gaza.

But it wasn’t only Chavez’s impact on the world stage and his support for Arab causes that earned him popular respect and admiration. The Arab public also admired Chavez’s achievements in Venezuela and Latin America, which also stood in sharp contrast to the failures, incompetence, and corruption of Arab regimes. Chavez succeeded in achieving greater economic and political integration in Latin America while pursuing progressive social and economic policies at home.

Arabs watched Chavez nationalize Venezuelan oil and use the increased revenues to help improve the lives of the most marginalized Venezuelans. Arabs watched their own oil profits squandered on the lavish lifestyles of indulgent sheikhs while Chavez cut poverty in half. Arabs also watched the rise of obscene skyscrapers and the construction of artificial islands as Chavez was investing in social programs to end illiteracy, expand education, and provide healthcare to the most impoverished areas of Venezuela.

Chavez and Nasser had much in common both on a personal and political level. Both came from a humble background, began their careers in the military, and then lead popular revolutions that changed their society. As with Nasser, Arab support and sympathy for Chavez was not emotional nor was it driven solely by a charismatic personality. Although both leaders were highly charismatic, enjoyed an emotional connection with their people, and brought them a greater degree of dignity, their support derived mainly from tangible accomplishments at home and abroad.

Chavez and Nasser were able to improve the quality of life for the neediest in their societies, and both men understood the struggle for freedom and social justice at home was intrinsically linked to the struggle against imperialism and foreign domination. For this, Chavez, like Nasser and all leaders that insist on full sovereignty and the right to pursue independent domestic and foreign policies, was also vilified by Western governments and media.

We often hear that Arab Nationalism is dead and that Arabs do not share any common concerns beyond the borders. US client regimes in the region and their hired propagandists have insisted Arabs no longer consider the liberation of Palestine the central cause of the Arab people and that anti-imperialist discourse is something of the past. Yet the passing of Chavez and the invocation of Nasser’s memory in the wake of his death show the exact opposite.

The overwhelming support for Chavez leaves no doubt that his vision for Venezuela represents many Arabs’ vision for their own future, and that must be very troubling for many people.

Thabit Al-Arabi is co-editor of Ikhras, an Arab-American website that covers Arab and Muslim American politics and activism. You can follow Ikhras on Twitter.

March 12, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Ethnic Cleansing, Racism, Zionism, Solidarity and Activism, Timeless or most popular | Arab, Arab world, Chavez, Gaza, Hugo Chávez, Israel, Palestine, Venezuela, Zionism |

Leave a comment

The funeral for Venezuelan president, Hugo Rafaél Chávez Frías, was held the morning of Friday March 8th, at the Military Academy in Caracas, Venezuela. 55 countries sent delegations to the funeral. 33 of them were headed by presidents or heads of government. In a strong show of unity and support, every single one of Latin America’s presidents, and most of the Caribbean’s heads of state were present at Chávez’s funeral (though the presidents of Brazil and Argentina left early).

This is a turnout with few precedents. The death of U.S. President John F. Kennedy in 1963 brought together a total of 19 heads of state. The funeral of President Ronald Reagan in 2004 gathered 36 former and current heads of state. The death of Hugo Chávez brought together at least 38 former and current heads of state.

The governments of Spain, France, Portugal, Lebanon, Finland, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Australia, Syria, Greece, Ukraine, Croatia, Jordan, Slovenia, Turkey, Gambia, China, and Russia sent fairly high level delegations to represent their governments at the funeral. Spain’s royal heir, the prince of Asturias, attended, as did the General Secretary of the Organization of American States José Miguel Insulza, the Reverend Jesse Jackson –who spoke at the funeral, actor Sean Penn, and the much celebrated Venezuelan orchestra director Gustavo Dudamel, who missed one of his shows at the Los Angeles Philharmonic to direct the Simón Bolívar Symphonic Orchestra at the funeral.

Though much of the major media has ignored this international show of recognition for the government of Hugo Chávez, these responses to his death are a clear affirmation of respect and acknowledgement for his legacy, from Latin America and around the world.

Again in contrast with the rest of the region, the United States sent no representative of the Obama administration to the funeral. James Derham, an official from the U.S. embassy in Venezuela attended the ceremony along with Congressman Gregory Meeks (D-NY) and former Congressman William Delahunt (D-MA). The morning of Chávez’s death, Vice President Nicolás Maduro expelled two U.S. embassy officials that he accused of violating diplomatic protocol, possibly contributing to the U.S.’s reluctance to send any administration official from Washington to the funeral.

Instead of giving the public a sense of the broad and historic show of international recognition of Chávez from so many countries, much of the major media focused on the attendance of U.S. “foe” President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran. For an interesting, balanced analysis of the relations between Iran and Venezuela this blog post by David Smilde is worth a read.

Days of Mourning

In another unprecedented show of acknowledgment for the legacy of Hugo Chávez, an astonishing number of countries – a total of 14 – decreed official days of mourning in response to President Chávez’s death. Nine Latin American countries declared three days of mourning (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Haiti, Peru and Uruguay), while two more, Bolivia and Nicaragua, like Venezuela, declared seven days each. From other regions of the world, Belarus, Nigeria and Iran declared three, seven and one day of mourning, respectively.

The Response from the Venezuelan Public

In addition to the strong reaction from around the world, the response from Chávez supporters in Venezuela was also unprecedented. From Thursday, when Chávez’s casket was put on display for public viewing until the time of the funeral, reportedly 2 million people had already paid their respects and bade farewell to their president, many of them waiting up to 12 hours in line for the opportunity to pass by his coffin. An 8 kilometer-long march, with hundreds of thousands of Chávez’s supporters, dressed in red, and pouring onto the streets, accompanied the procession of Chávez’s coffin from the hospital to the Military Academy where the funeral was held. Multitudes then viewed the funeral from outside of its location, watching on large screens as they waited for another opportunity to bid their president farewell.

March 11, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Progressive Hypocrite, Solidarity and Activism, Timeless or most popular | Hugo Chávez, Latin America, Nicolás Maduro, Obama, United States, Venezuela |

Leave a comment

President Hugo Chavez, who died on March 5, 2013 of cancer at age 58, marked forever the history of Venezuela and Latin America.

1. Never in the history of Latin America, has a political leader had such incontestable democratic legitimacy. Since coming to power in 1999, there were 16 elections in Venezuela. Hugo Chavez won 15, the last on October 7, 2012. He defeated his rivals with a margin of 10-20 percentage points.

2. All international bodies, from the European Union to the Organization of American States, to the Union of South American Nations and the Carter Center, were unanimous in recognizing the transparency of the vote counts.

3. James Carter, former U.S. President, declared that Venezuela’s electoral system was “the best in the world.”

4. Universal access to education introduced in 1998 had exceptional results. About 1.5 million Venezuelans learned to read and write thanks to the literacy campaign called Mission Robinson I.

5. In December 2005, UNESCO said that Venezuela had eradicated illiteracy.

6. The number of children attending school increased from 6 million in 1998 to 13 million in 2011 and the enrollment rate is now 93.2%.

7. Mission Robinson II was launched to bring the entire population up to secondary level. Thus, the rate of secondary school enrollment rose from 53.6% in 2000 to 73.3% in 2011.

8. Missions Ribas and Sucre allowed tens of thousands of young adults to undertake university studies. Thus, the number of tertiary students increased from 895,000 in 2000 to 2.3 million in 2011, assisted by the creation of new universities.

9. With regard to health, they created the National Public System to ensure free access to health care for all Venezuelans. Between 2005 and 2012, 7873 new medical centers were created in Venezuela.

10. The number of doctors increased from 20 per 100,000 population in 1999 to 80 per 100,000 in 2010, or an increase of 400%.

11. Mission Barrio Adentro I provided 534 million medical consultations. About 17 million people were attended, while in 1998 less than 3 million people had regular access to health. 1.7 million lives were saved, between 2003 and 2011.

12. The infant mortality rate fell from 19.1 per thousand in 1999 to 10 per thousand in 2012, a reduction of 49%.

13. Average life expectancy increased from 72.2 years in 1999 to 74.3 years in 2011.

14. Thanks to Operation Miracle, launched in 2004, 1.5 million Venezuelans who were victims of cataracts or other eye diseases, regained their sight.

15. From 1999 to 2011, the poverty rate decreased from 42.8% to 26.5% and the rate of extreme poverty fell from 16.6% in 1999 to 7% in 2011.

16. In the rankings of the Human Development Index (HDI) of the United Nations Program for Development (UNDP), Venezuela jumped from 83 in 2000 (0.656) at position 73 in 2011 (0.735), and entered into the category Nations with ‘High HDI’.

17. The GINI coefficient, which allows calculation of inequality in a country, fell from 0.46 in 1999 to 0.39 in 2011.

18. According to the UNDP, Venezuela holds the lowest recorded Gini coefficient in Latin America, that is, Venezuela is the country in the region with the least inequality.

19. Child malnutrition was reduced by 40% since 1999.

20. In 1999, 82% of the population had access to safe drinking water. Now it is 95%.

21. Under President Chavez social expenditures increased by 60.6%.

22. Before 1999, only 387,000 elderly people received a pension. Now the figure is 2.1 million.

23. Since 1999, 700,000 homes have been built in Venezuela.

24. Since 1999, the government provided / returned more than one million hectares of land to Aboriginal people.

25. Land reform enabled tens of thousands of farmers to own their land. In total, Venezuela distributed more than 3 million hectares.

26. In 1999, Venezuela was producing 51% of food consumed. In 2012, production was 71%, while food consumption increased by 81% since 1999. If consumption of 2012 was similar to that of 1999, Venezuela produced 140% of the food it consumed.

27. Since 1999, the average calories consumed by Venezuelans increased by 50% thanks to the Food Mission that created a chain of 22,000 food stores (MERCAL, Houses Food, Red PDVAL), where products are subsidized up to 30%. Meat consumption increased by 75% since 1999.

28. Five million children now receive free meals through the School Feeding Programme. The figure was 250,000 in 1999.

29. The malnutrition rate fell from 21% in 1998 to less than 3% in 2012.

30. According to the FAO, Venezuela is the most advanced country in Latin America and the Caribbean in the erradication of hunger.

31. The nationalization of the oil company PDVSA in 2003 allowed Venezuela to regain its energy sovereignty.

32. The nationalization of the electrical and telecommunications sectors (CANTV and Electricidad de Caracas) allowed the end of private monopolies and guaranteed universal access to these services.

33. Since 1999, more than 50,000 cooperatives have been created in all sectors of the economy.

34. The unemployment rate fell from 15.2% in 1998 to 6.4% in 2012, with the creation of more than 4 million jobs.

35. The minimum wage increased from 100 bolivars/month ($ 16) in 1998 to 2047.52 bolivars ($ 330) in 2012, ie an increase of over 2,000%. This is the highest minimum wage in Latin America.

36. In 1999, 65% of the workforce earned the minimum wage. In 2012 only 21.1% of workers have only this level of pay.

37. Adults at a certain age who have never worked still get an income equivalent to 60% of the minimum wage.

38. Women without income and disabled people receive a pension equivalent to 80% of the minimum wage.

39. Working hours were reduced to 6 hours a day and 36 hours per week, without loss of pay.

40. Public debt fell from 45% of GDP in 1998 to 20% in 2011. Venezuela withdrew from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, after early repayment of all its debts.

41. In 2012, the growth rate was 5.5% in Venezuela, one of the highest in the world.

42. GDP per capita rose from $ 4,100 in 1999 to $ 10,810 in 2011.

43. According to the annual World Happiness 2012, Venezuela is the second happiest country in Latin America, behind Costa Rica, and the nineteenth worldwide, ahead of Germany and Spain.

44. Venezuela offers more direct support to the American continent than the United States. In 2007, Chávez spent more than 8,800 million dollars in grants, loans and energy aid as against 3,000 million from the Bush administration.

45. For the first time in its history, Venezuela has its own satellites (Bolivar and Miranda) and is now sovereign in the field of space technology. The entire country has internet and telecommunications coverage.

46. The creation of Petrocaribe in 2005 allows 18 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, or 90 million people, secure energy supply, by oil subsidies of between 40% to 60%.

47. Venezuela also provides assistance to disadvantaged communities in the United States by providing fuel at subsidized rates.

48. The creation of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) in 2004 between Cuba and Venezuela laid the foundations of an inclusive alliance based on cooperation and reciprocity. It now comprises eight member countries which places the human being in the center of the social project, with the aim of combating poverty and social exclusion.

49. Hugo Chavez was at the heart of the creation in 2011 of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) which brings together for the first time the 33 nations of the region, emancipated from the tutelage of the United States and Canada.

50. Hugo Chavez played a key role in the peace process in Colombia. According to President Juan Manuel Santos, “if we go into a solid peace project, with clear and concrete progress, progress achieved ever before with the FARC, is also due to the dedication and commitment of Chavez and the government of Venezuela.”

Translation by Tim Anderson

March 10, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Economics, Timeless or most popular | Hugo Chávez, Latin America, Union of South American Nations, Venezuela |

1 Comment

One of the more bizarre takes on Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez’s death comes from Associated Press business reporter Pamela Sampson (3/5/13):

Chavez invested Venezuela’s oil wealth into social programs including state-run food markets, cash benefits for poor families, free health clinics and education programs. But those gains were meager compared with the spectacular construction projects that oil riches spurred in glittering Middle Eastern cities, including the world’s tallest building in Dubai and plans for branches of the Louvre and Guggenheim museums in Abu Dhabi.

That’s right: Chavez squandered his nation’s oil money on healthcare, education and nutrition when he could have been building the world’s tallest building or his own branch of the Louvre. What kind of monster has priorities like that?

In case you’re curious about what kind of results this kooky agenda had, here’s a chart (NACLA, 10/8/12) based on World Bank poverty stats–showing the proportion of Venezuelans living on less than $2 a day falling from 35 percent to 13 percent over three years. (For comparison purposes, there’s a similar stat for Brazil, which made substantial but less dramatic progress against poverty over the same time period.)

Of course, during this time, the number of Venezuelans living in the world’s tallest building went from 0 percent to 0 percent, while the number of copies of the Mona Lisa remained flat, at none. So you have to say that Chavez’s presidency was overall pretty disappointing–at least by AP‘s standards.

March 8, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Economics, Mainstream Media, Warmongering, Supremacism, Social Darwinism, Timeless or most popular | Associated Press, Chavez, Hugo Chávez, Jim Naureckas, Venezuela |

Leave a comment

By Joe Emersberger | ZCommunications | March 7th 2013

The death of Hugo Chavez provoked HRW to immediately (within hours) smear the Chavez government’s legacy.

“Chávez’s Authoritarian Legacy: Dramatic Concentration of Power and Open Disregard for Basic Human Rights” said the Washington DC based NGO.

If that isn’t harsh enough, in a tweet sent out in June of 2012, Ken Roth, executive director of HRW, described Venezuela as being one of the “most abusive” in Latin America. Ecuador and Bolivia were the other two states that Roth singled out.

In November of 2012, HRW also rushed out a letter demanding that Venezuela be excluded from the UN’s Human Rights Council on the grounds that the Chavez government “fell far short of acceptable standards”

It is staggeringly obvious that HRW did not simply regard the Chavez government as one which could be validly criticized, like any other in the world, on human rights grounds. HRW regarded Venezuela under Chavez as one of the “most abusive” countries in the world. Make no mistake, if Venezuela is more abusive than Colombia, as Roth alleged, then that would easily place Venezuela among the worst human rights abusers on earth.

The day Hugo Chavez died, HRW rehashed the accusations it has been making for years:

1) “Assault on Judicial Independence”

2) “Assault on Press Freedoms”

3) “Rejection of Human Rights Scrutiny”

4) “Embracing Abusive Governments”

Without exploring any details at all about these criticisms something should stand out right away. Putting aside HRW’s remarkably shoddy attempts to substantiate them, how could these criticisms place the Chavez government among the most abusive countries in the world? How could HRW’s assessment, even taken at face value, make Venezuela unworthy to sit on the UN’s Human Rights Council next to the USA?

Daniel Kovalik pointed out the following amazing facts last year in a Counterpunch article:

… in a November 19, 2009 U.S. Embassy Cable, entitled, ” International Narcotics Control Strategy Report,” the U.S. Embassy in Bogota acknowledges, as a mere aside, the horrific truth:257,089 registered victimsof the right-wing paramilitaries. And, as Human Rights Watch just reported in its 2012 annual report on Colombia, these paramilitaries continue to work hand-in-glove with the U.S.-supported Colombian military….

… the U.S. has been quite aware of this death toll for over two years, though this knowledge has done nothing to change U.S. policy toward Colombia — which is slated to receive over $500 million in military and police aid from the U.S. in the next two years.

…. Indeed, as the U.S. Embassy acknowledges in a February 26, 2010 Embassy Cable entitled, ” Against Indigenous Shows Upward Trend,” such violence is pushing 34 indigenous groups to the point of extinction. This violence, therefore, can only be described as genocidal.

Either Ken Roth is unfamiliar with his own organization’s reports, or something very rotten drives his groups’ ludicrously disproportionate criticism of Venezuela.

I’ll borrow from HRW’s playbook and do some rehash of my own. I’ll rehash some of the questions I’ve been asking them for years. HRW has never attempted to answer.

1) When a coup deposed Chavez for 2 days in 2002, why did HRW’ public statements fail to do obvious things like denounce the coup, call on other countries not to recognize the regime, invoke the OAS charter, and (especially since HRW is based in Washington) call for an investigation of US involvement?

2) Very similarly, when a coup deposed Haiti’ democratically elected government in 2004, why didn’t HRW condemn the coup, call on other countries not to recognize the regime, invoke the OAS charter, and call for an investigation of the US role? Many of these things were done by the community of Caribbean nations (CARICOM). A third of the UN General Assembly called for an investigation into the overthrow of Aristide. Why didn’ HRW back them up?

3) Since 2004, why has HRW written about 20 times more about Venezuela than about Haiti despite the fact that the coup in Haiti created a human rights catastrophe in which thousands of political murders were perpetrated and the jails filled with political prisoners? Haiti’ judiciary remains stacked with holdovers from the coup installed regime.

In honour of Chavez and of the Venezuelan movements which will hopefully expand on the progress made towards making Venezuela a more democratic and humane country, lets recall some achievements of his government on the international stage that HRW would never applaud. Let’s remember Hugo Chavez strongly opposing the US bombing of Afghanistan in 2001; the war in Iraq, the 2004 coup in Haiti, the 2009 coup in Honduras, NATO’s bombing of Libya, the lethal militarization of the conflict in Syria, the attempted coups against Morales in Bolivia and against Correa in Ecuador, Israel’s aggression in Lebanon and in the Occupied Territories.

None of that impressed HRW in the least. It may even have aggravated HRW’s hatred of the Chavez government, but it should impress people who really care about human rights.

March 7, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Deception, Mainstream Media, Warmongering, Timeless or most popular | Haiti, HRW, Hugo Chávez, Human rights, Human Rights Watch, Venezuela |

Leave a comment

Not One Step Backward, Ni Un Paso Atrás

Hugo Chávez is no more, and yet the symbolic importance of the Venezuelan President that exceeded his physical persona in life, providing a condensation point around which popular struggles coalesced, will inevitably continue to function long after his death. It’s not for nothing that the words of the great revolutionary folk singer Alí Primera are on the tip of many tongues:

Los que mueren por la vida

no pueden llamarse muertos

—

Those who die for life

cannot be called dead.

A Barefoot Revolutionary

Hugo Chávez was a poor kid from the country, which tells you much of what you need to know about him. Bare feet, mud hut, perpetual sunburn, gleaning hard lessons and a strong dose of audacity from everyday experiences in that wild part of the Venezuelan flatlands, or llanos, that crash abruptly into the towering Andes mountains.

While politics was in the soil under his feet and in his every social interaction, Chávez’s first formal contact with revolutionary politics came through his elder brother, Adán, a member of the still-clandestine former guerrilla organization, Party of the Venezuelan Revolution (PRV). It was the PRV that refused intransigently to come down from the mountains in the late 1960s when the Venezuelan Communist Party decided to withdraw from the armed struggle, and it was the PRV more than any other organization that resisted Marxist orthodoxy by excavating Venezuelan and Latin American revolutionary traditions under the umbrella of “Bolivarianism.”

Through Adán, Chávez the younger was imbued with the legacy of this Venezuelan guerrilla struggle and its aspirations, a necessary and portentous counterbalance to the official doctrine he would learn in the military academy. But even as a soldier, Chávez was always irreverent to the core, and it wasn’t long before he had begun to organize with other radical officers. Their conspiratorial grouping would eventually be called the MBR-200, the Bolivarian Revolutionary Movement, and it was not a purely military affair, evolving in close contact with revolutionary communist guerrillas from the PRV and elsewhere.

The Old Venezuela

The old Venezuela is no more. The Venezuelan ancien regime was one of self-professed harmony, and it cultivated this myth to the very end. For political scientists, this translated as “Venezuelan exceptionalism”: in a sea of unrest and dictatorship, it alone remained relatively stable and “democratic.” But this was a harmony premised on the invisibility of the majority, and a stability crafted through the incorporation and neutralization of any and all oppositional movements. Those who refused to concede were murdered or imprisoned in the gulags of this “exceptional” democracy.

When Hugo Chávez first attempted to overthrow the Venezuelan government of Carlos Andrés Pérez in 1992, he was attacking a democracy in name only. Decades of two-party rule had created a system that was utterly unresponsive to the needs of the vast majority, and as economic crisis set in during the “lost decade” of the 1980s, the poor turned to rebellion and the government to brute repression. In only the most spectacular of many moments of resistance, the week-long 1989 rebellion known as the Caracazo, somewhere between 300 and 3,000 were slaughtered as Pérez ordered the military to “restore order” in the poor barrios that surround Caracas and other Venezuelan cities.

It was this rebellion more than any other, and the repression it unleashed, that led, nay forced, Chávez and others to attempt a coup with the support of revolutionary grassroots movements, and it was this coup more than any other event that led to his eventual election in 1998. Finally someone had taken a stand, and when Chávez promised on national television that the conspirators had only failed “por ahora, for now,” he was effectively promising, as did Fidel Castro nearly 40 years prior, that history would absolve him.

The New Venezuela

In many ways, it has. Under Chávez’s watch, Venezuela has become more equal, the most egalitarian country in Latin America in fact, according to the Gini coefficient of income distribution. Poverty has been reduced significantly, and extreme poverty almost stamped out. Illiteracy has been eliminated and education is freely accessible, through the university level, to even the poorest Venezuelans. Health care is free and universal. Despite catastrophic language used by the Venezuelan opposition and foreign press, the economy is strong, and has weathered the global economic crisis better than most (notably, the United States).

More important than this improvement in the social welfare of the Venezuelan majority, however, are the political transformations that the Venezuelan state and people have undergone, transformations that remain far from complete. This was not merely a populist government that sought to buy votes through handouts, but a radically democratic government that sought, often despite its own autocratic tendencies, to empower the people to intervene from below as the true “protagonists” of history. Through communal councils, cooperatives, communes, and popular militias, the Venezuelan government has radically empowered the radical grassroots, albeit not without resistance from its own bureaucrats.

But these accomplishments do not belong to Chávez alone, and in fact, they do not belong to Chávez at all. Long before Chávez, there were the revolutionary movements that tried, failed, and tried better, generating the experiences, organizations, and outlooks that would eventually propel Chávez to the helm of an untrustworthy state. Any celebration of Chávez that presents him as a savior is an insult to the people he held in such high esteem, and whose orders he followed.

Inversely, some ill-informed leftists decry him as not having been revolutionary enough, not moving quickly enough toward socialism: the revolution must be all at once or not at all. Others, here taking a page from the liberals, attack him for being authoritarian, autocratic, and undemocratic. But this all misses the most fundamental point: that the Venezuelan revolution is not Chávez. If we fail to understand why many millions of Venezuelans are in mourning today, then we have voluntarily abandoned any serious effort to understand what is going on in Venezuela.

A Combative Democrat

Even as President, Chávez’s rural persona always managed to break through the polite veneer of political leadership: as when he would often spontaneously break into llanero song, speak in country parables and refrains, or brutally attack opponents and allies alike on live television. Also arguably a legacy of the countryside was his paradoxical democratic authoritarianism: deeply respectful of the people and fervently egalitarian, he would not take no for an answer when it came to revolutionizing the country. While Chávez had long dreamed of becoming a major league pitcher, his childhood nickname, latigo, the whip, described his approach to politics at least as well as it described his fastball.

But this contradiction was not his own: direct democracy and representative democracy are rarely the sympathetic allies their names might suggest, and one of the seeming paradoxes of the Bolivarian Revolution is that it has taken a firm push from above to clear the way for radically democratic participation from below. This is what critics of Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution mean when they suggest that he has run roughshod over democratic “checks and balances,” failing to note that such institutional constraints, however justifiable, are often far from democratic.

As a result, the two sides seem to speak completely different languages: for the one, which seems to include Republican Congressman Ed Royce bid a quick “good riddance” to Chávez, the leader was an authoritarian dictator. Such claims come as a surprise to Chavistas, however, who have elected him many times, repeatedly choosing the path of an increasingly radical revolutionary process, and who are quick to point out the contradiction between their democratic will and term limits. Many poor Venezuelans, too, were surprised at the outrage that ensued when Chávez referred to George W. Bush as “the devil” or as a “donkey.” The poor rarely grasp the role of politeness in politics, seeing it instead, intuitively but correctly, as the realm of powerful oppositions, of Bush’s own “you’re with us or you’re against us.”

The Manichean nature of Venezuelan politics in recent years has been undeniable, but we would be well advised to recognize, with Frantz Fanon, that this division between us and them, Chavistas and escualidos (or more recently, majunches), was more a reflection of a structural reality than the fault of Chávez or the Revolution. While elite Venezuelans began to mourn the disappearance of Venezuelan “harmony,” what they really meant was that, all of a sudden, poor and dark-skinned Venezuelans had appeared, had made their presence felt, and had even assumed the mantle of the government as a mechanism for pressing their demands.

Chávez certainly courted Manicheanism to mobilize the people in the struggle, but this Manicheanism also came to him, for phenotypic as well as political reasons: dark-skinned, with a wide nose and large ears, “with his very image, Chávez has shaken up the beehive of social harmony… His image upsets the wealthy women of Cuarimare.” Chávez and his supporters have long been racialized in terms that would seem scandalous anywhere else: monkey, blackie, scum, horde, rabble. Open racism exploded during the 2002 coup that unseated Chávez for less than two days, in many ways forcing him to recognize it publicly in a country that had often celebrated mestizaje and insisted that there was no racism in Venezuela. In the end, this Manicheanism has become the most important motor for driving the revolutionary process forward, unifying the people against a common enemy and preparing them for the struggle ahead.

I was supposed to meet Hugo Chávez, but he cancelled at the last minute. His unpredictability stemmed from a combination of security concerns and an irrepressible desire to do everything himself. The closest I ever got was about 10 feet away, awash in a rushing torrent of red-shirted Chavistas on the Avenida Bolívar in 2007, as the now late President drove by atop a truck. As he passed, I reached up and performed my favorite Chavista gesture: pounding palm with fist to symbolize the brutal pummeling of the opposition. As though confirming the centrality of combat in a Revolution that would outlive him, he looked at me and did the same.

The Revolution Will Not Be Reversed

What will happen next? Within 30 days, there will be elections, in which Chávez’s hand-picked successor Nicólas Maduro will almost certainly prevail against an opposition that only seems to ever come together for the purposes of then falling apart. But the future in the longer term remains unwritten. While nothing is inevitable, however, a great many poor and radicalized Venezuelans will tell you that they will not take ni un paso atras, a single step back, and that conversely, no volverán, they shall not return. And they mean it.

This is a revolutionary assurance that has never depended solely on the figure of Chávez. As I write in the introduction to my forthcoming book We Created Chávez:

“The Bolivarian Revolution is not about Hugo Chávez. He is not the center, not the driving force, not the individual revolutionary genius on whom the process as a whole relies or in whom it finds a quasi-divine inspiration. To paraphrase the great Trinidadian theorist and historian C.L.R. James: Chávez, like the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture, ‘did not make the revolution. It was the revolution that made’ Chávez. Or, as a Venezuelan organizer told me, ‘Chavez didn’t create the movements, we created him.’”

In 1959, Frantz Fanon declared the Algerian Revolution irreversible, despite the fact that the country would not gain formal independence for another three years. Studying closely the transformation of Algerian culture during the course of the struggle and the creation of what he called a “new humanity,” Fanon was certain that a point of no return had been reached, writing that:

“An army can at any time reconquer the ground lost, but how can the inferiority complex, the fear and the despair of the past be re-implanted in the consciousness of the people?”

In revolution, there are no guarantees, and there’s no saying that the historical dialectic cannot be bent back upon itself, beaten and bloody. The point is simply that for the forces of reaction to do so will be no easy task. Long ago, the Venezuelan people stood up, and it is difficult if not impossible to tell a people on their feet to get back down on their knees.

George Ciccariello-Maher, teaches political theory at Drexel University in Philadelphia. He is the author of We Created Chávez: A People’s History of the Venezuelan Revolution (Duke University Press, May 2013), and can be reached at gjcm(at)drexel.edu.

March 7, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Economics, Solidarity and Activism, Timeless or most popular | Alí Primera, Caracas, Chavez, Communist Party of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez, Venezuela |

Leave a comment

Thousands of saddened Venezuelans poured into the streets of Caracas crying, hugging each other and shouting slogans in support of President Hugo Chavez after learning of his death. “I feel such big pain I cannot even speak,” said Yamilina Barrios, a 39-year-old office worker, to the Associated Press. “He was the best thing the country had … I adore him. Let´s hope the country calms down and we can continue the tasks he left us.”

Leaders of the continent also showed their sorrow. “We are devastated by the death of the brother Hugo Chavez,” Prensa Latina agency quoted Bolivian president Evo Morales as saying, while he was accompanied by several members of his cabinet. Chavez was “a caring brother, a fellow revolutionary, a Latin American who fought for his country, for the great homeland, as Simon Bolivar did. He gave his whole life for the liberation of the Venezuelan people, the people of Latin America and all anti-imperialist fighters in the world”.

Chavez dedicated his whole life to the cause of the oppressed and poor, the integration and unity of Latin America, the construction of a multipolar world and the fight against the imperialism. Hugo Chavez died due to the illness he had, which many suspect was inoculated to him by any of his enemies, starting by the US government.

He became notorious after a group of army officers and soldiers, led by him, tried to overthrow in 1992 the corrupt and criminal pro-US government of Venezuelan President Carlos Andres Perez, a social democratic politician who ordered a brutal and bloody crackdown on demonstrators that were protesting against IMF-austerity measures on February 27 1989. About 3,000 people were killed by troops in that episode known as “the Caracazo”.

Chavez spent two years in a military prison. After being released, he led a Boliviarian movement that had two main goals: social justice for the impoverished majority of Venezuelans and independence from the US Empire and its financial tools. In 1998, he won his first presidential election and he would never lose one from then on.

The President changed the leadership of the oil national company, PDVSA, whose revenues had benefited only a small national oligarchy and US corporations up to then. At the same time, Chavez funded various social assistance programs for the poor. These programs have improved literacy levels, health care, housing and income levels for Venezuela´s majority.

During Chavez´s years in office, poverty has been cut a half and extreme poverty by 70%. Millions of Venezuelans have had access to health care for the first time, and college enrollment doubled, with free tuition for many students. Inequality was also considerably reduced. By contrast, the two decades that preceded Chavez, Venezuela was one of the worst economic failures in Latin America, with real income per person actually falling by 14% from 1980-1998.

Chavez was the main promoter of the process for the integration of Latin America. It would lead to the creation of some Latin American blocs, such as ALBA, UNASUR or CELAC, which reduced US-dominated OAS to irrelevance. US plans to control Latin American economies through a continental free trade agreement also failed due to the opposition of Venezuela and some other countries.

Following Chavez´s revolution, Latin America has elected in recent years a group of leaders -Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua- who are deeply involved in the fight for social justice in their societies and political independence for their countries and the continent on the whole. Other leaders who followed that trend -Manuel Zelaya in Honduras and Fernando de Lugo in Paraguay- were illegally toppled by US-supported right-wing coups.

In the international field, Chavez was an active promoter of a multipolar world. In order to liberate his country from an imperialist control, Venezuela established solid links with Russia, China, Iran, Syria and other countries. He supported the fight of the Palestinian people against the Zionist occupation.

Due to all these policies, Chavez earned the implacable hatred and hostility of Washington. In April 2002, the CIA backed a military coup to overthrow him. A group of right-wing leaders and generals arrested and imprison him and took over the power, in a move widely welcomed by the US and some European governments and media. However, he was saved and restored to power two days later by the rapid action of loyal military officers and soldiers and a huge popular uprising.

Even after the failure of the coup, the right-wing sectors, which dominated some private media outlets, especially channels as Venevision, Univision and Globovision, continued their permanent campaign against Chavez and his government. All kind of dirty games, including a politicized general strike, were put in place in order to overthrow him. However, all these plans failed due to the high political awareness of the Venezuelan people.

For its part, Washington used its agencies, including the CIA, to fund the political opposition and the oligarchy. According to the site venezuelanalysis.com, Capriles and the Venezuelan opposition received 20 million dollars from US organizations, such as USAID and the National Endowment for Democracy.

Media campaigns were also used as a weapon of preference against the Venezuelan government. Despite Chavez´s repeated electoral victories, successive US administrations and corporate media presented his rule as illegitimate and dictatorial. The US Embassy in Caracas became a hub of anti-Chavez activities, as it shows the recent expulsion of the US Air Force attaché, Col. David Delmonaco, and his deputy, who allegedly tried to recruit Venezuelan army officers for “destabilizing projects.”

In this context, the statement by US President, Barack Obama, which claims that Washington wants to normalize its relations with Caracas, is hypocritically insincere. Actually, the US is just attempting to look for new mechanisms to recover its control over Venezuela and change its economic, social and foreign policy.

The death of President Chavez will force the country to conduct another presidential election within 30 days. The candidate and new leader of the Bolivarian movement, Vice-President Nicolas Maduro, will be the candidate who will confront Henrique Capriles, the right-wing governor of Miranda state, who was comfortably defeated by Chavez in a presidential election held last October.

Although Washington and its Venezuelan allies hope that the death of Chavez may help them put an end to the Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela and Latin America, there are many reasons to think otherwise. The people of Venezuela are aware of the achievements and progress that has obtained at this late stage and is not willing to renounce them. On the other hand, the early, and still not clarified death of Chavez, will reinforce his figure, turning it into a symbol of a policy for the oppressed, for the independence and integration of Latin America and for a world free from imperialism.

“Oligarchies are surely celebrating when the peoples that fight for their freedom and dignity and work for equality are suffering. But it does not matter, the only thing that matters is that we are united, we fight for liberation. A lot of strength, a lot of unity. The best tribute to Chavez is unity. Unity to fight, to work for the equality of all peoples of the world,” Morales said.

March 6, 2013

Posted by aletho |

Economics, Timeless or most popular | Chavez, Hugo Chávez, Latin America, United States, Venezuela |

Leave a comment