How does the Gates Foundation spend its money to feed the world?

GRAIN | November 4, 2014

“Listening to farmers and addressing their specific needs. We talk to farmers about the crops they want to grow and eat, as well as the unique challenges they face. We partner with organizations that understand and are equipped to address these challenges, and we invest in research to identify relevant and affordable solutions that farmers want and will use.” – First guiding principle of the Gates Foundation’s work on agriculture.1

At some point in June this year, the total amount given as grants to food and agriculture projects by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation surpassed the US$3 billion mark. It marked quite a milestone. From nowhere on the agricultural scene less than a decade ago, the Gates Foundation has emerged as one of the world’s major donors to agricultural research and development.

The Gates Foundation is arguably the biggest philanthropic venture ever. It currently holds a $40 billion endowment, made up mostly of contributions from Gates and his billionaire friend Warren Buffet. The foundation has over 1,200 staff, and has given over $30 billion in grants since its inception in 2000, $3.6 billion in 2013 alone.2 Most of the grants go to global health programmes and educational work in the US, traditionally the foundation’s priority areas. But in 2006-2007, the foundation massively expanded its funding for agriculture, with the launch of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) and a series of large grants to the international agricultural research system (CGIAR). In 2007, it spent over half a billion dollars on agricultural projects and has maintained funding at around this level. The vast majority of the foundation’s agricultural grants focus on Africa.

Spending so much money gives the foundation significant influence over agricultural research and development agendas. As the weight of the foundation’s overall focus on technology and private sector partnerships has begun to be felt in the global agriculture arena, it has raised opposition and controversy, particularly around its work in Africa. Critics say that the Gates Foundation is promoting an imported model of industrial agriculture based on the high-tech seeds and chemicals sold by US corporations. They say the foundation is fixated on the work of scientists in centralised labs and that it chooses to ignore the knowledge and biodiversity that Africa’s small farmers have developed and maintained over generations. Some also charge that the Gates Foundation is using its money to impose a policy agenda on Africa, accusing the foundation of direct intervention on highly controversial issues like seed laws and GMOs.

GRAIN looked through the foundation’s publicly available financial records to see if the actual flows of money support these critiques. We combed through all the grants for agriculture that the Gates Foundation gave between 2003 and September 2014.3 We then organised the grant recipients into major groupings (see table 2) and constructed a database, which can be downloaded here.4

Here are some of the conclusions we were able to draw from the data.

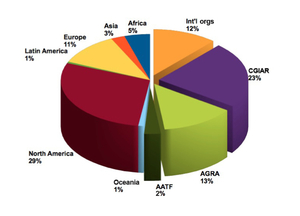

1. The Gates Foundation fights hunger in the South by giving money to the North.

Graph 1 and Table 1 give the overall picture. Roughly half of the foundation’s grants for agriculture went to four big groupings: the CGIAR’s global agriculture research network, international organisations (World Bank, UN agencies, etc.), AGRA (set up by Gates itself) and the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF). The other half ended up with hundreds of different research, development and policy organisations across the world. Of this last group, over 80% of the grants were given to organisations in the US and Europe, 10% went to groups in Africa, and the remainder elsewhere. Table 2 lists the top 10 countries where Gates grantees are located and the amounts they received, highlighting some of the main grantees. By far the main recipient country is Gates’s own home country, the US, followed by the UK, Germany and the Netherlands.

When it comes to agricultural grants by the foundation to universities and national research centres across the world, 79% went to grantees in the US and Europe, and a meagre 12% to recipients in Africa.

The North-South divide is most shocking, however, when we look at the NGOs that the Gates Foundation supports. One would assume that a significant portion of the frontline work that the foundation funds in Africa would be carried out by organisations based there. But of the $669 million that the Gates Foundation has granted to non-governmental organisations for agricultural work, over three quarters has gone to organisations based in the US. Africa-based NGOs get a meagre 4% of the overall agriculture-related grants to NGOs.

2. The Gates Foundation gives to scientists, not farmers

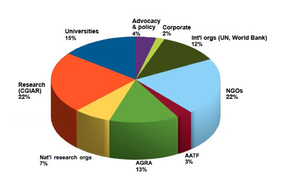

As can be seen in Graph 2, the single biggest recipient of grants from the Gates Foundation is the CGIAR, a consortium of 15 international agricultural research centres. In the 1960s and 70s, these centres were responsible for the development and spread of a controversial Green Revolution model of agriculture in parts of Asia and Latin America which focused on the mass distribution of a few varieties of seeds that could produce high yields – with the generous application of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Efforts to implement the same model in Africa failed and, globally, the CGIAR lost relevance as corporations like Syngenta and Monsanto took control over seed markets. Money from the Gates Foundation is providing CGIAR and its Green Revolution model a new lease on life, this time in direct partnership with seed and pesticide companies.5

Click to enlarge – Graph 2: the Gates Foundation’s $3 billion pie (agriculture grants, by type of organisation).

The CGIAR centres have received over $720 million from Gates since 2003. During the same period, another $678 million went to universities and national research centres across the world – over three-quarters of them in the US and Europe – for research and development of specific technologies, such as crop varieties and breeding techniques.

The Gates Foundation’s support for AGRA and the AATF is tightly linked to this research agenda. These organisations seek, in different ways, to facilitate research by the CGIAR and other research programmes supported by the Gates Foundation and to ensure that the technologies that come out of the labs get into farmers’ fields. AGRA trains farmers on how to use the technologies, and even organises them into groups to better access the technologies, but it does not support farmers in building up their own seed systems or in doing their own research.6

We could find no evidence of any support from the Gates Foundation for programmes of research or technology development carried out by farmers or based on farmers’ knowledge, despite the multitude of such initiatives that exist across the continent. (African farmers, after all, do continue to supply an estimated 90% of the seed used on the continent!) The foundation has consistently chosen to put its money into top down structures of knowledge generation and flow, where farmers’ are mere recipients of the technologies developed in labs and sold to them by companies.

3. The Gates Foundation buys political influence

Does the Gates Foundation use its money to tell African governments what to do? Not directly. The Gates Foundation set up the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa in 2006 and has supported it with $414 million since then. It holds two seats on the Alliance’s board and describes it as the “African face and voice for our work”.7

AGRA, like the Gates Foundation, provides grants to research programmes. It also funds initiatives and agribusiness companies operating in Africa to develop private markets for seeds and fertilisers through support to “agro-dealers” (see box on Malawi). An important component of its work, however, is shaping policy.

AGRA intervenes directly in the formulation and revision of agricultural policies and regulations in Africa on such issues as land and seeds. It does so through national “policy action nodes” of experts, selected by AGRA, that work to advance particular policy changes. For example, in Ghana, AGRA’s Seed Policy Action Node drafted revisions to the country’s national seed policy and submitted it to the government. The Ghana Food Sovereignty Network has been fiercely battling such policies since the government put them forward. In Mozambique, AGRA’s Seed Policy Action Node drafted plant variety protection regulations in 2013, and in Tanzania it reviewed national seed policies and presented a study on the demand for certified seeds. Also in Tanzania, its Land Policy Action Node is involved in revising the Village Land Act as well as “reviewing laws governing land titling at the district level and working closely with district officials to develop guidelines for formulation of by-laws.”8

The African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF) is another Gates Foundation supported organisation that straddles the technology and policy arenas. Since 2008, it has received $95 million from the Gates Foundation, which it used to to support the development and distribution of hybrid maize and rice varieties. But it also uses funds from the Gates Foundation to “positively change public perceptions” about GMOs and to lobby for regulatory changes that will increase the adoption of GM products in Africa.9

In a similar vein, the Gates Foundation provides Harvard University University with funds to promote discussion of biotechnology in Africa, Michigan University with a grant to set up a centre to help African policymakers decide on how best to use biotechnology, and Cornell University with funds to create a global “agricultural communications platform” so that people better understand science-based agricultural technologies, with AATF as a main partner.

Gates & AGRA in Malawi: organising the agro-dealers

One of AGRA’s core programmes in Africa is the establishment of “agro-dealer” networks: small, private stockists who sell chemicals and seeds to farmers. In Malawi, AGRA provided a $4.3 million grant for the Malawi Agro-dealer Strengthening Programme (MASP) to supply hybrid maize seeds and chemical pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers.

The main supplier to the agro-dealers in Malawi has been Monsanto, responsible for 67% of all inputs. A Monsanto country manager disclosed that all of Monsanto’s sales of seeds and herbicides in Malawi are made through AGRA’s agro-dealer network.

“Agro-dealers… act as vessels for promoting input suppliers’ products,” says one MASP project document. Another states: “supply companies have expressed their appreciation for field days because MASP trained agro-dealers are helping them promote their products in the very remotest areas of Malawi.” Training the agro-dealers on product knowledge is carried out by the corporate suppliers of the products themselves. In addition, these agro-dealers are increasingly the source of farming advice to small farmers, and an alternative to the government’s agricultural extension service.

A project evaluation report states that 44% of the agro-dealers in the programme were providing extension services. According to the World Bank: “The agro-dealers have… become the most important extension nodes for the rural poor… A new form of private sector driven extension system is emerging in these countries.” The agro-dealer project in Malawi has been implemented by CNFA, a US-based organisation funded by the Gates Foundation, USAID and DFID, and its local affiliate the Rural Market Development Trust (RUMARK), whose trustees include four seed and chemical suppliers: Monsanto, SeedCo, Farmers World and Farmers Association.

Listening to farmers?

“Listening to farmers and addressing their specific needs” is the first guiding principle of the Gates Foundation’s work on agriculture.10 But it is hard to listen to someone when you cannot hear them. Small farmers in Africa do not participate in the spaces where the agendas are set for the agricultural research institutions, NGOs or initiatives, like AGRA, that the Gates Foundation supports. These spaces are dominated by foundation reps, high-level politicians, business executives, and scientists.

Listening to someone, if it has any real significance, should also include the intent to learn. But nowhere in the programmes funded by the Gates Foundation is there any indication that it believes that Africa’s small farmers have anything to teach, that they have anything to contribute to research, development and policy agendas. The continent’s farmers are always cast as the recipients, the consumers of knowledge and technology from others. In practice, the foundation’s first guiding principle appears to be a marketing exercise to sell its technologies to farmers. In that, it looks, not surprisingly, a lot like Microsoft. … Full article with tables and notes

Reblogged this on TheFlippinTruth.

LikeLike