The Myth of Online Radicalisation

By Iain Davis | The Disillusioned Blogger | May 10, 2021

In 2021, following the tragic murder of David Amess MP, the UK legacy media reported that Ali Harbi Ali, the man subsequently convicted of murdering Mr Amess, was quite possibly radicalised online:

Social media users could face a ban on anonymous accounts, as home secretary Priti Patel steps up action to tackle radicalisation in the wake of the murder of MP David Amess. [. . .] Police questioning Ali Harbi Ali on suspicion of terrorism offences are understood to be investigating the possibility that the 25-year-old [. . .] was radicalised by material found on the internet and social media networks during lockdown.

The police had already stated that the crime was being investigated as a terrorist incident. They reported a potential motive of Islamist extremism.

Ali Harbi Ali had been known to the UK government’s Prevent counter-radicalisation program for seven years, prior to murdering Mr Amess. In 2014 Ali Harbi Ali was referred to the Channel counter-terrorism programme, a wing of Prevent reserved for the most radical youths. A referral to Channel can only have come from the UK Police. The official guidance for a Channel referral states:

The progression of referrals is monitored at the Home Office for a period, with a view to offering further support if needed. An audit of non-adopted referrals is undertaken where these did not progress to police management. The Home Office works with Counter Terrorism Policing Headquarters to share any concerns and agree necessary steps for improvement in partnership with the local authority and police.

It is likely, therefore, that Ali Harbi Abedi was known to the UK government, counter-terrorism police and the intelligence agencies. Yet we are told, having been flagged as among the most concerning of all Prevent subjects, for some seemingly inexplicable reason, Ali Harbi Ali was not known to the intelligence agencies. To date, there has been no explanation for this, frankly, implausible claim.

Following his conviction, the UK legacy media reported that Ali Harbi Ali was an example of “textbook radicalisation.” This was a quite extraordinary claim because there is no such thing as “textbook radicalisation.”

Ali Harbi Ali said that he had watched ISIS propaganda videos online. This was also highlighted at his trial. Consequently, the BBC reported:

[. . .] for a potentially bored teenager living a humdrum life in suburban London – the [Syrian] war not only appeared like an exciting video game on social media, it came packaged with an appealing message that there was a role for everyone else. [. . .] Harbi Ali told himself he could [. . .] join the ranks of home-grown attackers – on the basis of an instruction [online videos] from an IS propagandist who played a major role in the spread of terrorism attacks in western Europe.

The story we are supposed to believe about Ali Harbi Ali’s alleged path toward radicalisation is that he became a terrorist and a murderer because he watched YouTube videos and engaged in online groups that support terrorism. This is complete nonsense.

What is the Radicalisation Process?

In 2016, the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur Ben Emmerson issued a report to inform potential UN strategies to counter extremism and terrorism. Emmerson reported there was neither an agreed-upon definition of “extremism” nor any single cogent explanation of the “radicalisation” process:

[M]any programmes directed at radicalisation [are] based on a simplistic understanding of the process as a fixed trajectory to violent extremism with identifiable markers along the way. [. . .] There is no authoritative statistical data on the pathways towards individual radicalisation.

This was followed, in 2017, with the publication of “Countering Domestic Extremism” by the US National Academy of Sciences (NAS). The NAS report stated that domestic “violence and violent extremist ideologies” were eventually adopted by a small minority of people as the result of a complex and poorly understood “radicalisation” process.

According to the NAS, there were numerous contributory factors to an individual’s apparent radicalisation, including sociopolitical and economic factors, personality traits, psychological influences, traumatic life experiences and so on. Precisely how these elements combined, and why some people were radicalised, while the majority who experienced the same weren’t, remained unknown:

No single shared motivator for violent extremism has been found, but the sum of several could provide a strong foundation for understanding

In July 2018, researcher team from from Deakin University in Australia largely corroborated Emmerson’s and NAS’ findings. Adding some further detail and research, their peer-reviewed article, “The 3 P’s of Radicalisation,” was based upon an meta-analysis of all the available academic literature on the radicalisation. They identified three broad drivers that could potentially lead someone toward violent extremism. They called these Push, Pull, and Personal factors.

Push factors are created by the individuals perception of their social or political environment. Awareness of things likes state repression, structural deprivation, poverty, and injustice can lead to resentment and anger. Pull factors are the elements of extremism that appeal to the individual. This might include an ideological commitment, a group identity and sense of belonging, finding a purpose, promises of justice, eternal glory, etc. Personal factors are the aspects of an individual’s personality that may predispose them to being more vulnerable to Push or Pull influences. For example, mental health problems or illness, individual characteristics, their reaction to life experiences and more.

Currently, the UN cites it’s own report—Journey To Extremism in Africa—as “the most extensive study yet on what drives people to violent extremism.” Building on the work we’ve just discussed, the report concluded that radicalisation is the product of numerous factors that combine to lead an individual down a path to extremism and possible violence.

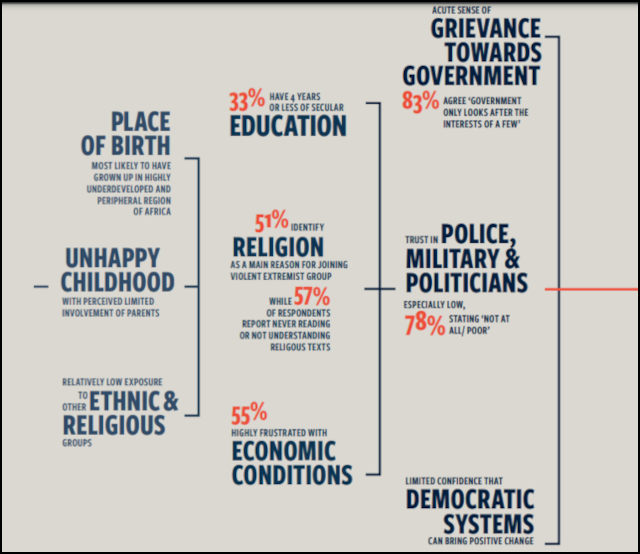

The myriad of contributory factors to the radicalisation process acording to the UN’s “best study.”

The UN stated:

We know the drivers and enablers of violent extremism are multiple, complex and context specific, while having religious, ideological, political, economic and historical dimensions. They defy easy analysis, and understanding of the phenomenon remains incomplete.

The BBC report of “textbook radicalisation” was total rubbish. Everything we know about the radicalisation process reveals a convoluted interplay between social, economic, political, cultural and personal factors. These factors, which “defy easy analysis,” may combine to lead someone toward violent extremism and potentially terrorism. In the overwhelming majority of cases they do not.

It is extremely difficult to predict which individual’s may be radicalised. Millions of people experience all of the Push, Pull and Personal contributory factors and only a minuscule minority turn to extremism and violence.

We can say that watching videos and hanging around in online chat groups may be part of the radicalisation process but, absent all the other contributory elements, in no way is it reasonable to claim that anyone becomes a terrorist simply because they are “radicalised online.” The suggestion is absurd.

This absurdity was emphasised by the UN in its June 2023 publication of its report “Prevention of Violent Extremism.” The UN reported:

[. . .] deaths from terrorist activity have fallen considerably worldwide in recent years.

During the same period global internet use had increased by 45%, from 3.7 billion people in 2018 to 5.4 billion in 2023. Quite clearly, if there is a correlation between internet use and terrorism—doubtful—it’s an inverse one.

Adopting the precautionary principle we should perhaps be encouraging more people to have more access to a wider range of online information sources. There is a remote, but possible chance that this assists, in some unknown way, the reduction of violent extremism and deters the tiny minority from turning toward terrorism.

Marianna Spring

Exploiting the Online Radicalisation Myth

State propagandists, like the BBC’s Marianna Spring, have been spreading disinformation about online radicalisation for some time. They have been doing this to deceive the public into thinking that government legislation, such as the Online Safety Act (OSA), will tackle the mythical problem of online radicalisation.

In a January 2024 article she titled “Young Britons exposed to online radicalisation following Hamas attack,” Marianna Spring wrote:

It is a spike in hate that leaves young Britons increasingly exposed to radicalisation by algorithm. [. . .] Algorithms are recommendation systems that promote new content to a user based on posts they engage with. That means they can drive some people to more extreme ideas.

Building on her absurd Lord Haw-Haw level tripe, in reference to the work of the UK Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU) Spring added:

The focus is on terrorism-related content that could lead to violence offline or risk radicalising other people into terror ideologies on social media.

Building on this abject nonsense Spring continued:

So what about all of the hate that sits in the middle? It’s not extreme enough to be illegal, but it still poisons the public discourse and risks pushing some people further towards extremes. [. . .] Responsibility for dealing with hateful posts – as of now – lies with the social media companies. It also lies, to some extent, with policy makers looking to regulate the sites, and users themselves. New legislation like the Online Safety Act does force the social media companies to take responsibility for illegal content, too.

This blurring of definitions from “terrorist” to “hate” to “hateful posts” to “extremes” was a meaningless slurry of specious drivel designed to convince the public that terrorists become terrorists because they watch YouTube videos or are influenced by the “hurty words” they read and share on social media. None of which was true.

Spring’s evident purpose was to lend some credibility to the State’s legislative push to silence all dissent online and censor legitimate public opinion. Spring spun the idea, that online radicalisation exists, to encourage people to give away their essential democratic rights in order to stay safe.

This moronic argument convinced the clueless puppeticians—we keep electing to Parliament by mistake—to pass the Online Safety Act into law in October 2023. They were told that it would protect children and adults from “harm”:

The kinds of illegal content and activity that platforms need to protect users from are set out in the Act, and this includes content relating to [. . .] terrorism.

Imagining this is what the Online Safety Act was supposed to protect adults from, the OSA received its Royal assent. Now that we have it on the statute books all the anti-democratic oppression it contains has been let loose.

The UK’s Online Safety Act (OSA) creates the offence of “sending false information intended to cause non-trivial harm.” Quite what “non-trivial harm” is supposed to mean isn’t entirely clear. The UK Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) certainly doesn’t understand it:

Section 179(1) OSA 2023 creates a summary offence of sending false communications. The offence is committed if [. . .], at the time of sending it, the person intended the message, or the information in it, to cause non-trivial psychological or physical harm to a likely audience. [. . .] Non-trivial psychological or physical harm is not defined [. . .]. Prosecutors should be clear when making a charging decision about what the evidence is concerning the suspect’s intention and how what was intended was not “trivial”, and why. Note that there is no requirement that such harm should in fact be caused, only that it be intended.

Its seems the legal profession can’t quite grasp the horrific implications of the new punishable offence the UK State has created. Perhaps because they still imagine they serve a democracy. There’s no need for any confusion. The UK State has been quite clear about the nature of its dictatorship:

These new criminal offences will protect people from a wide range of abuse and harm online, including [. . .] sending fake news that aims to cause non-trivial physical or psychological harm.

“Fake news” is whatever the State, the Establishment and their “epistemic authorities” say it is. what constitutes “non-trivial harm” is also an entirely subjective judgement for the State. The Online Safety regulator, Ofcom, will decree the truth and the State will punish those who dare to contradict its official proclamations based upon whatever the Secretary of State tells Ofcom to outlaw.

If you think this sounds like “thought crime,” you are right. That is precisely what it is.

The idea that the OSA has something to do with protecting children and deterring people from online radicalisation was a sales pitch. Propagandists like the BBC’s Marianna Spring were dispatched to make the ridiculous arguments to deceive the public into believing their own speech needs to be regulated by the State.

The State is Completely Disinterested In Terrorist Content Online

Inciting violence, crime or promoting terrorism, sharing child porn and the online paedophile grooming of children has been illegal in the UK for many years. The Online Safety Act adds absolutely nothing to existing laws. The problem has never been insufficient law it has been insufficient enforcement.

In addition, it couldn’t be more obvious that the UK State and its propagandists are not in the least bit interested in tackling alleged “online radicalisation.” It is revealed in Marianna Spring’s article (referenced above) she reportedly got her wacky ideas about online radicalisation from CTIRU team members.

The CTIRU was set up in 2010 to remove “unlawful terrorist material” from the Internet. It makes formal requests to social media and hosting companies to take down material deemed to be terrorist related. If online radicalisation were a thing, which it isn’t, the CTIRU has been tasked for 14 years with stopping it. It doesn’t appear to have done anything at all.

The group Jabhat Fateh al Sham (JFS) was formerly known as the Al-Nusra Front or Jabhat al-Nusra (alias al-Qaeda in Syria, or al-Qaeda in the Levant). It subsequently merged with Ansar al-Din Front, Jaysh al-Sunna, Liwa al-Haqq, and the Nour al–Din al-Zenki Movement to form Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), or ‘Levant Liberation Front’.

HTS’ objective is to create an Islamic state in the Levant. According to the UK Government’s listing of proscribed terrorist groups:

The government laid Orders, in July 2013, December 2016 and May 2017, which provided that the “al-Nusrah Front (ANF)”, “Jabhat al-Nusrah li-ahl al Sham”, “Jabhat Fatah al-Sham” and “Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham” should be treated as alternative names for the organisation which is already proscribed under the name Al Qa’ida.

HTS, then, is officially defined as Al-Qa’ida. It is the same group supposedly responsible for 9/11.

In 2016, six years after the CTIRU was formed, BBC Newsnight interviewed Al-Qa’ida’s Director of Foreign Media Relations, Mostafa Mahamed, about the ambitions of Al-Qa’ida. The BBC gave him ample airtime to explain how Al-Qa’ida was leading the fight against the elected Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad. The BBC claimed that JFS—now HTS—had formerly split from Al-Qa’ida. Probably attempting to justify its promotion of a proscribed terrorist organisation. The UK Government does not share the BBC appraisal but its Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit doesn’t appear to be overly fussed.

The BBC HTS promo video is still available to watch on YouTube. Alternatively, you could watch a JFS promotional video, or perhaps spend less than a minute searching YouTube to find the slew of videos it provides promoting proscribed Islamist terrorist groups.

You can still watch Channel 4’s in-depth 2016 report extolling the heroics of the Nour al-Din al-Zenki terrorists. This is the group that publicly beheaded a twelve-year-old boy. In fact, Channel 4 promoted those directly responsible for the despicable crime. Channel 4 said the child murderers had won a “famous victory”.

When it was pointed out that these people decapitate children, the BBC leapt to their defence, pointing out that the child was probably a combatant. The BBC didn’t ask its terrorist interviewee, Mostafa Mahamed, whether he was against murdering children in principle.

Such videos have been available online for years and have been shared liberally by mainstream media outlets such as Al-Jazeera, Channel 4, the BBC, AP, France24 and many others. This all seems rather odd, because in 2018, then CTIRU Commander Clarke Jarrett said:

It’s vital that if the public see something online they think could be terrorist-related, that they ACT and flag it up to us. Our Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU) has specialist officers who not only take action to get content removed, but also increasingly, are in a position to look at those behind online content — which is leading to more and more investigations.

What does CTIRU mean by “terrorist-related” if not promotional videos made by terrorist organisations? How much investigation is needed to “take down” BBC interviews with Al-Qa’ida spokesmen, and to prosecute those who made and broadcast it?

Why aren’t the hundreds, if not thousands, of terrorist promos currently available via Google services deemed unlawful? Are only some terrorist groups unlawful while others are fine? Why are some terrorists promoted and others not?

The truth is the whole thing is a monumental sham. Not only is online radicalisation a myth the State couldn’t care less about terrorist promotional material. The online radicalisation myth has been punted by propagandists for one reason only. To convince you to submit to online censorship.

No comments yet.

Leave a comment