Ex-US soldier guilty of rape, murder found hanged in prison

Al-Akhbar | February 19, 2014

A former US soldier, sentenced to life imprisonment for the 2006 rape and murder of a 14-year-old Iraqi girl as well as the murder of her parents and six-year-old sister, has been found hanged in his cell.

According to American media reports, prison officials said the death of Steven Dale Green, found hanging in his Arizona cell last week, was currently being investigated as an act of suicide.

Green, 28, was convicted in 2009 for the rape and murder of 14-year-old Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi and the deaths of her father, mother and six-year-old sister in Mahmudiya, more than 30 kilometers south of Baghdad.

He was sentenced to life in prison after a federal jury in Kentucky could not decide whether he should be given the death penalty.

Prosecutors portrayed Green as the ringleader of five soldiers that plotted to invade the home of the family of four in order to rape the girl. They had later bragged about the crime to their peers in the army.

The four other soldiers were taken to military courts. Three of the soldiers pleaded guilty in the attack and the fourth was convicted. They received sentences ranging from five to 100 years.

Green, on the other hand, was tried as a civilian because he was arrested after he was discharged from the army.

February 19, 2014 Posted by aletho | Timeless or most popular, War Crimes | Iraq, Mahmudiyah killings, United States, United States Army | Leave a comment

Bowman Expedition 2.0 Targets Indigenous Communities in Central America

By Joe Bryan | Public Political Ecology Lab | July 23, 2013

The Lawrence World-Journal recently reported the Defense Department’s decision to fund the latest Bowman Expedition led by the American Geographical Society and the University of Kansas Geography Department. Like the first – and controversial – Bowman expedition to Mexico, this latest venture will be led by KU Geographers Jerome Dobson and Peter Herlihy and will target indigenous communities.

Like previous Bowman Expeditions, the expedition’s goal is to compile basic, “open-source,” information about countries that can be used to inform U.S. policy makers and the military. This time, however, they won’t be focused on a single country. Instead they’ll be working throughout Central America, a region that Herlihy and Dobson have elsewhere called “The U.S. Borderlands.” What is this Expedition about? And why is the Defense Department funding academic research on indigenous peoples?

As with the expedition to Mexico, Herlihy and Dobson are focused on land ownership. Echoing a growing list of military strategists, Herlihy and Dobson contend that areas where property rights are not clearly established and enforced by states provide ideal conditions for criminal activity and violence that threaten regional security.

Herlihy and Dobson propose to use maps made with indigenous communities of their lands to clarify this problem, ostensibly with an eye towards securing legal recognition of their property rights. In their expedition to Mexico, Herlihy and Dobson turned over their findings to Radiance Technologies, an Alabama-based military contractor specializing in “creative solutions for the modern warfighter.” It’s not clear whether this new expedition will do the same, though the program funding it, the Minerva Research Initiative, evaluates proposals according to their ability to address national security concerns.

The rationale for these Expeditions has been parsed in film, print, and by academics (myself included), revealing them to be little more than intelligence gathering efforts carried out by civilian professors and their graduate students. Zapotec communities visited by the previous expedition to Mexico have further denounced Herlihy’s and Dobson’s efforts as “geopiracy,” (and again here) that replay some of colonialism’s oldest tactics of extracting information from communities for people (the U.S. Army) who live elsewhere. Zapotec communities in Oaxaca have also accused Herlihy of failing to inform them of the U.S. Army’s role in funding the Expedition and process data collected by it.

Military funding for the latest Bowman Expedition raises the question of what the U.S. military wants to know about Central America. Moreover, why is it funding research on indigenous peoples? It’s hard to imagine that the U.S. military has much interest in the nuances that distinguish, say, Tawahka communities from Emberá ones. Nor does the military appear concerned with the chronic insecurity of land rights, which continues to be one of the primary threats faced by indigenous communities. A far more likely answer lies with the military’s growing interest in collecting information about the “cultural” or “human” terrain that they can use as needed for a variety of purposes, from managing risks posed by natural disasters to planning military interventions.

Maps of the sort produced by the Bowman Expeditions are certainly useful for this task compiling information about who lives where and place names, to give two examples. But maps can only describe the territory. What they cannot describe are the intricacies of the “terrain” such as the social networks through which access to land and resources are negotiated or the history of struggles over land.

The U.S. military is more familiar with this terrain than one might think. Beginning with the “Banana Wars” of the early 20th Century, the U.S. military has intervened more times in Central America that just about any other region in the world. Indeed the Marines’ first resource on counter-insurgency, the “Small Wars Manual,” drew extensively from their experiences navigating the indigenous Mayanagna and Miskito communities in pursuit of Augusto Sandino’s anti-imperialist forces in Nicaragua.

In the 1980s, U.S. military advisors once again traversed the indigenous areas of Central America for tactical gain. In eastern Nicaragua and Honduras, they helped train and organize Miskito-led armed groups as part of the proxy battle strategy of the Contra War. In Guatamala they targeted Maya communities as bastions of guerilla support with genocidal consequence. Dense forests and other isolated areas throughout the region further provided cover for airstrips also used for illicit shipments of cocaine and weapons orchestrated by the Reagan Administration in support of the Contras.

Herlihy knows this history well. He’s been mapping the forested areas in eastern Honduras used by the Contras and Miskito armed groups since the late 1980s. Herlihy’s (and Dobson’s) main military contact, Geoffrey Demarest, knows this history too. A graduate of the School of the Americas, he served as a military attaché to Guatemala. He’s since become an expert on counter-insurgency, publishing extensively from his experience in Colombia and its relevance for current wars. More recently, he enrolled in the Geography Ph.D. program at KU under Dobson’s supervision.

Still, what is the national security interest in Central America that a Bowman Expedition there can help address? Indigenous land ownership has already been extensively mapped in much of the region as part of property reforms supported by the likes of the World Bank. Several countries in the region now also have promising laws on the books recognizing indigenous and black land rights.

Yet neither maps nor legal reforms have been enough to stop the region from becoming a major transshipment route for cocaine en route to the United States. The State Department estimates that more than 80 percent of cocaine bound for the U.S. passes through Honduras. Some of this trafficking makes use of infrastructure created by counter-insurgency campaigns in the 1980s.

In 2011, Herlihy once again mapped the Honduran Mosquitia as part of another U.S. Army-funded Bowman Expedition. Shortly thereafter, in 2012, the region was targeted by the DEA who made use of counter-insurgency tactics developed in Iraq to fight traffickers. Among those lessons of Iraq applied in the Mosquitia was the use of forward operating bases immersed in the region’s physical and cultural terrain of the Mosquitia. Two of those bases, El Aguacate and Mocorón, were repurposed bases constructed during the Contra War. The campaign fits a broader pattern of escalating militarization of Central America further illustrated by this map compiled by the interfaith Fellowship of Reconciliation.

The application of counter-insurgency tactics gives mapping indigenous areas a more sinister edge. Historically the U.S. military has relied on the designation of “Indian Country” and “tribal areas” to designate areas at the edge of state control, often turning them into free-fire zones where the conventions of war, legal and otherwise, do not apply. Better knowledge of these areas has scarcely reduced incidents of violent conflict as Dobson suggests. Instead, that knowledge has served as a “force multiplier” – to use General Petraeus’s term – that allows the U.S. military to intervene with greater efficiency. Herlihy and Dobson claim to champion the rights of indigenous peoples, but the money and data trail suggests that is only a secondary concern to U.S. military interests.

So why is the U.S. military funding academic geographers to do research in indigenous areas in Central America instead of relying on its own people to do the work? In Iraq and Afghanistan, the Army has relied on social scientists embedded with combat units as part of the Human Terrain System program to gather similar information. Funding academic researchers to do similar work poses a number of advantages. For starters, it sidesteps the ethical controversy raised by the Human Terrain System. It also brings the added benefit of relying on “civilian” researchers to access communities who might otherwise be wary of soldiers in military uniform. At the same time, it gives the military precisely the kind of detailed, georeferenced information – the spatial “metadata” – sought by the Human Terrain System for areas that lie far from current combat zones. It’s an approach consistent with what geographer Derek Gregory describes as the “everywhere war” currently waged across society on the whole by covert military teams, surveillance, and drones. By taking the measure of indigenous communities according to security interests, the Bowman Expeditions stand to perpetuate a role that is far too common in Geography’s history. The Bowman Expeditions have generated some productive debate (see also here, here, and here) in this regard, though in a context of shrinking budgets for university research and education the allure of military money remains powerful enough to trump ethical concerns.

Meanwhile as geographers debate the merits of military funding, indigenous peoples continue facing a long list of violent threats from drug trafficking, illegal logging, loss of lands, and institutional racism. The military-funded Bowman Expeditions merely add to that list. Still, as the Zapotec communities in Oaxaca forcefully remind us, it’s their information and the decision to participate in projects like the Bowman Expeditions – or any other research — ultimately resides with them. Herlihy’s and Dobson’s failure to address those concerns will only diminish their access to this field, undermining the kinds of rights and free exchange of knowledge they profess to support.

~

See Also: U.S. Military Funded Mapping Project in Oaxaca: University Geographers Used to Gather Intelligence?

Military-backed Mapping Project in Oaxaca Under Fire

Joe Bryan is an Assistant Professor of Geography at the University of Colorado at Boulder. For additional resources on the Bowman Expedition, see Zoltán Grossman’s fantastic website.

July 24, 2013 Posted by aletho | Deception, Militarism, Timeless or most popular | Bowman Expedition, Central America, Herlihy, Indigenous People, Mexico, Peter Herlihy, United States, United States Army | Leave a comment

When War has Passed – Vietnam

journeymanpictures | April 3, 2008

Related articles

- Death by defoilant, US war on the environment (alethonews.wordpress.com)

October 23, 2012 Posted by aletho | Militarism, Timeless or most popular, Video, War Crimes | United States, United States Army, Vietnam, Vietnam War | 2 Comments

The Hidden Story of the Americans that Finished the Vietnam War

Excerpts and adaptation:

by Joel Geier

Our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and noncommissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near-mutinous Conditions exist among American forces in Vietnam that have only been exceeded in this century by… the collapse of the Tsarist armies in 1916 and 1917.

– Armed Forces Journal, June 1971

The most neglected aspect of the Vietnam War is the soldiers’ revolt–the mass upheaval from below that unraveled the American army. It is a great reality check in an era when the U.S. touts itself as an invincible nation. For this reason, the soldiers’ revolt has been written out of official history.

The army revolt pitted enlisted soldiers against officers who viewed them as expendable. Liberal academics have reduced the radicalism of the 1960s to middle-class concerns and activities, while ignoring military rebellion. But the militancy of the 1960s began with the Black liberation struggle, and it reached its climax with the unity of White and Black soldiers.

A working-class army

From 1964 to 1973, from the Gulf of Tonkin resolution to the final withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam, 27 million men came of draft age. A majority of them were not drafted due to college, professional, medical or National Guard deferments. Only 40 percent were drafted and saw military service. A small minority, 2.5 million men (about 10 percent of those eligible for the draft), were sent to Vietnam.

This small minority was almost entirely working-class or rural youth. Their average age was 19. Eighty-five percent of the troops were enlisted men; 15 percent were officers. The enlisted men were drawn from the 80 percent of the armed forces with a high school education or less. At this time, college education was universal in the middle class.

In the elite colleges, the class discrepancy was even more glaring. The upper class did none of the fighting. Of the 1,200 Harvard graduates in 1970, only 2 went to Vietnam, while working-class high schools routinely sent 20 percent, 30 percent of their graduates and more to Vietnam.

College students who were not made officers were usually assigned to noncombat support and service units. High school dropouts were three times more likely to be sent to combat units that did the fighting and took the casualties. Combat infantry soldiers, “the grunts,” were entirely working class. They included a disproportionate number of Black working-class troops. Blacks, who formed 12 percent of the troops, were often 25 percent or more of the combat units.

When college deferments expired, joining the National Guard was a favorite way to get out of serving in Vietnam. During the war, 80 percent of the Guard’s members described themselves as joining to avoid the draft. You needed connections to get in–which was no problem for Dan Quayle, George W. Bush and other draft evaders. In 1968, the Guard had a waiting list of more than 100,000. It had triple the percentage of college graduates that the army did. Blacks made up less than 1.5 percent of the National Guard. In Mississippi, Blacks were 42 percent of the population, but only one Black man served in a Guard of more than 10,000.

The middle-class officers corps

The officer corps was drawn from the 7 percent of troops who were college graduates, or the 13 percent who had one to three years of college. College was to officer as high school was to enlisted man. The officer corps was middle class in composition and managerial in outlook.

Superfluous support officers lived far removed from danger, lounging in rear base camps in luxurious conditions. A few miles away, combat soldiers were experiencing a nightmarish hell. The contrast was too great to allow for confidence–in both the officers and the war–to survive unscathed.

Westmoreland’s solution to the competition for combat command poured gasoline on the fire. He ordered a one-year tour of duty for enlisted men in Vietnam, but only six months for officers. The combat troops hated the class discrimination that put them at twice the risk of their commanders. They grew contemptuous of the officers, whom they saw as raw and dangerously inexperienced in battle.

Even a majority of officers considered Westmoreland’s tour inequality as unethical. Yet they were forced to use short tours to prove themselves for promotion. They were put in situations in which their whole careers depended on what they could accomplish in a brief period, even if it meant taking shortcuts and risks at the expense of the safety of their men–a temptation many could not resist.

The outer limit of six-month commands was often shortened due to promotion, relief, injury or other reasons. The outcome was “revolving-door” commands. As an enlisted man recalled, “During my year in-country I had five second-lieutenant platoon leaders and four company commanders. One CO was pretty good…All the rest were stupid.”

Aggravating this was the contradiction that guaranteed opposition between officers and men in combat. Officer promotions depended on quotas of enemy dead from search-and-destroy missions. Battalion commanders who did not furnish immediate high body counts were threatened with replacement. This was no idle threat–battalion commanders had a 30 to 50 percent chance of being relieved of command. But search-and-destroy missions produced enormous casualties for the infantry soldiers. Officers corrupted by career ambitions would cynically ignore this and draw on the never-ending supply of replacements from the monthly draft quota.

Officer corruption was rife. A Pentagon official writes, “the stench of corruption rose to unprecedented levels during William C. Westmoreland’s command of the American effort in Vietnam.” The CIA protected the poppy fields of Vietnamese officials and flew their heroin out of the country on Air America planes. Officers took notice and followed suit. The major who flew the U.S. ambassador’s private jet was caught smuggling $8 million of heroin on the plane.

The war was fought by NLF troops and peasant auxiliaries who worked the land during the day and fought as soldiers at night. They would attack ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) and American troops and bases or set mines at night, and then disappear back into the countryside during the day. In this form of guerrilla war, there were no fixed targets, no set battlegrounds, and there was no territory to take. With that in mind, the Pentagon designed a counterinsurgency strategy called “search and destroy.” Without fixed battlegrounds, combat success was judged by the number of NLF troops killed–the body count. A somewhat more sophisticated variant was the “kill ratio”–the number of enemy troops killed compared to the number of Americans dead. This “war of attrition” strategy was the basic military plan of the American ruling class in Vietnam.

For each enemy killed, for every body counted, soldiers got three-day passes and officers received medals and promotions. This reduced the war from fighting for “the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese” to no larger purpose than killing. Any Vietnamese killed was put in the body count as a dead enemy soldier, or as the GIs put it, “if it’s dead, it’s Charlie” (“Charlie” was GI slang for the NLF). This was an inevitable outcome of a war against a whole people. Everyone in Vietnam became the enemy–and this encouraged random slaughter. Officers further ordered their men to “kill them even if they try to surrender–we need the body count.” It was an invitation to kill indiscriminately to swell a tally sheet.

Rather than following their officers, many more soldiers had the courage to revolt against barbarism.

Ninety-five percent of combat units were search-and-destroy units. Their mission was to go out into the jungle, hit bases and supply areas, flush out NLF troops and engage them in battle. If the NLF fought back, helicopters would fly in to prevent retreat and unleash massive firepower–bullets, bombs, missiles. The NLF would attempt to avoid this, and battle generally only occurred if the search-and-destroy missions were ambushed. Ground troops became the live bait for the ambush and firefight. GIs referred to search and destroy as “humping the boonies by dangling the bait.”

Without helicopters, search and destroy would not have been possible–and the helicopters were the terrain of the officers. “On board the command and control chopper rode the battalion commander, his aviation-support commander, the artillery-liaison officer, the battalion S-3 and the battalion sergeant major. They circled…high enough to escape random small-arms fire.” The officers directed their firepower on the NLF down below, but while indiscriminately spewing out bombs and napalm, they could not avoid “collateral damage”–hitting their own troops. One-quarter of the American dead in Vietnam was killed by “friendly fire” from the choppers. The officers were out of danger, the “eye in the sky,” while the troops had their “asses in the grass,” open to fire from both the NLF and the choppers.

When the battle was over, the officers and their choppers would fly off to base camps removed from danger while their troops remained out in the field.

Of the 543,000 American troops in Vietnam in 1968, only 14 percent (or 80,000) were combat troops. These 80,000 men took the brunt of the war. They were the weak link, and their disaffection crippled the ability of the world’s largest military to fight. In 1968, 14,592 men–18 percent of combat troops–were killed. An additional 35,000 had serious wounds that required hospitalization. Although not all of the dead and wounded were from combat units, the overwhelming majority were. The majority of combat troops in 1968 were either seriously injured or killed. The number of American casualties in Vietnam was not extreme, but as it was concentrated among the combat troops, it was a virtual massacre. Not to revolt amounted to suicide.

Officers, high in the sky, had few deaths or casualties. The deaths of officers occurred mostly in the lower ranks among lieutenants or captains who led combat platoons or companies. The higher-ranking officers went unharmed. During a decade of war, only one general and eight full colonels died from enemy fire. As one study commissioned by the military concluded, “In Vietnam… the officer corps simply did not die in sufficient numbers or in the presence of their men often enough.”

The slaughter of grunts went on because the officers never found it unacceptable. There was no outcry from the military or political elite, the media or their ruling-class patrons about this aspect of the war, nor is it commented on in almost any history of the war. It is ignored or accepted as a normal part of an unequal world, because the middle and upper class were not in combat in Vietnam and suffered no pain from its butchery. It never would have been tolerated had their class done the fighting. Their premeditated murder of combat troops unleashed class war in the armed forces. The revolt focused on ending search and destroy through all of the means the army had provided as training for these young workers.

Tet–the revolt begins

The Tet Offensive was the turning point of the Vietnam War and the start of open, active soldiers’ rebellion. At the end of January 1968, on Tet, the Vietnamese New Year, the NLF sent 100,000 troops into Saigon and 36 provincial capitals to lead a struggle for the cities. The Tet Offensive was not militarily successful, because of the savagery of the U.S. counterattack. In Saigon alone, American bombs killed 14,000 civilians. The city of Ben Tre became emblematic of the U.S. effort when the major who retook it announced that “to save the city, we had to destroy it.”

Westmoreland and his generals claimed that they were the victors of Tet because they had inflicted so many casualties on the NLF. But to the world, it was clear that the U.S. had politically lost the war in Vietnam. Tet showed that the NLF had the overwhelming support of the Vietnamese population–millions knew of and collaborated with the NLF entry into the cities and no one warned the Americans. The ARVN had turned over whole cities without firing a shot. In some cases, ARVN troops had welcomed the NLF and turned over large weapons supplies. The official rationale for the war, that U.S. troops were there to help the Vietnamese fend off Communist aggression from the North, was no longer believed by anybody. The South Vietnamese government and military were clearly hated by the people.37

Westmoreland’s constant claim that there was “light at the end of the tunnel,” that victory was imminent, was shown to be a lie. Search and destroy was a pipe dream. The NLF did not have to be flushed out of the jungle, it operated everywhere. No place in Vietnam was a safe base for American soldiers when the NLF so decided.

What, then, was the point of this war? Why should American troops fight to defend a regime its own people despised? Soldiers became furious at a government and an officer corps who risked their lives for lies. Throughout the world, Tet and the confidence that American imperialism was weak and would be defeated produced a massive, radical upsurge that makes 1968 famous as the year of revolutionary hope. In the U.S. army, it became the start of the showdown with the officers.

Mutiny

The refusal of an order to advance into combat is an act of mutiny. In time of war, it is the gravest crime in the military code, punishable by death. In Vietnam, mutiny was rampant, the power to punish withered and discipline collapsed as search and destroy was revoked from below.

Until 1967, open defiance of orders was rare and harshly repressed, with sentences of two to ten years for minor infractions. Hostility to search-and-destroy missions took the form of covert combat avoidance, called “sandbagging” by the grunts. A platoon sent out to “hump the boonies” might look for a safe cover from which to file fabricated reports of imaginary activity.

But after Tet, there was a massive shift from combat avoidance to mutiny. One Pentagon official reflected that “mutiny became so common that the army was forced to disguise its frequency by talking instead of ‘combat refusal.’” Combat refusal, one commentator observed, “resembled a strike and occurred when GIs refused, disobeyed, or negotiated an order into combat.”

Acts of mutiny took place on a scale previously only encountered in revolutions. The first mutinies in 1968 were unit and platoon-level rejections of the order to fight. The army recorded 68 such mutinies that year. By 1970, in the 1st Air Cavalry Division alone, there were 35 acts of combat refusal. One military study concluded that combat refusal was “unlike mutinous outbreaks of the past, which were usually sporadic, short-lived events. The progressive unwillingness of American soldiers to fight to the point of open disobedience took place over a four-year period between 1968-71.”

The 1968 combat refusals of individual units expanded to involve whole companies by the next year. The first reported mass mutiny was in the 196th Light Brigade in August 1969. Company A of the 3rd Battalion, down to 60 men from its original 150, had been pushing through Songchang Valley under heavy fire for five days when it refused an order to advance down a perilous mountain slope. Word of the mutiny spread rapidly. The New York Daily News ran a banner headline, “Sir, My Men Refuse To Go.” The GI paper, The Bond, accurately noted, “It was an organized strike…A shaken brass relieved the company commander…but they did not charge the guys with anything. The Brass surrendered to the strength of the organized men.”

This precedent–no court-martial for refusing to obey the order to fight, but the line officer relieved of his command–was the pattern for the rest of the war. Mass insubordination was not punished by an officer corps that lived in fear of its own men. Even the threat of punishment often backfired. In one famous incident, B Company of the 1st Battalion of the 12th Infantry refused an order to proceed into NLF-held territory. When they were threatened with court-martials, other platoons rallied to their support and refused orders to advance until the army backed down.

As the fear of punishment faded, mutinies mushroomed. There were at least ten reported major mutinies, and hundreds of smaller ones. Hanoi’s Vietnam Courier documented 15 important GI rebellions in 1969. At Cu Chi, troops from the 2nd Battalion of the 27th Infantry refused battle orders. The “CBS Evening News” broadcast live a patrol from the 7th Cavalry telling their captain that his order for direct advance against the NLF was nonsense, that it would threaten casualties, and that they would not obey it. Another CBS broadcast televised the mutiny of a rifle company of the 1st Air Cavalry Division.

When Cambodia was invaded in 1970, soldiers from Fire Base Washington conducted a sit-in. They told Up Against the Bulkhead, “We have no business there…we just sat down. Then they promised us we wouldn’t have to go to Cambodia.” Within a week, there were two additional mutinies, as men from the 4th and 8th Infantry refused to board helicopters to Cambodia.

In the invasion of Laos in March 1971, two platoons refused to advance. To prevent the mutiny from spreading, the entire squadron was pulled out of the Laos operation. The captain was relieved of his command, but there was no discipline against the men. When a lieutenant from the 501st Infantry refused his battalion commander’s order to advance his troops, he merely received a suspended sentence.

The decision not to punish men defying the most sacrosanct article of the military code, the disobedience of the order for combat, indicated how much the deterioration of discipline had eroded the power of the officers. The only punishment for most mutinies was to relieve the commanding officer of his duties. Consequently, many commanders would not report that they had lost control of their men. They swept news of mutiny, which would jeopardize their careers, under the rug. As they became quietly complicit, the officer corps lost any remaining moral authority to impose discipline.

For every defiance in combat, there were hundreds of minor acts of insubordination in rear base camps. As one infantry officer reported, “You can’t give orders and expect them to be obeyed.” This democratic upsurge from below was so extensive that discipline was replaced by a new command technique called working it out. Working it out was a form of collective bargaining in which negotiations went on between officers and men to determine orders. Working it out destroyed the authority of the officer corps and gutted the ability of the army to carry out search-and-destroy missions. But the army had no alternative strategy for a guerrilla war against a national liberation movement.

The political impact of the mutiny was felt far beyond Vietnam. As H.R. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, reflected, “If troops are going to mutiny, you can’t pursue an aggressive policy.” The soldiers’ revolt tied down the global reach of U.S. imperialism.

Fragging

The murder of American officers by their troops was an openly proclaimed goal in Vietnam. As one GI newspaper demanded, “Don’t desert. Go to Vietnam, and kill your commanding officer.” And they did. A new slang term arose to celebrate the execution of officers: fragging. The word came from the fragmentation grenade, which was the weapon of choice because the evidence was destroyed in the act.

In every war, troops kill officers whose incompetence or recklessness threatens the lives of their men. But only in Vietnam did this become pervasive in combat situations and widespread in rear base camps. It was the most well-known aspect of the class struggle inside the army, directed not just at intolerable officers, but at “lifers” as a class. In the soldiers’ revolt, it became accepted practice to paint political slogans on helmets. A popular helmet slogan summed up this mood: “Kill a non-com for Christ.” Fragging was the ransom the ground troops extracted for being used as live bait.

No one knows how many officers were fragged, but after Tet it became epidemic. At least 800 to 1,000 fragging attempts using explosive devices were made. The army reported 126 fraggings in 1969, 271 in 1970 and 333 in 1971, when they stopped keeping count. But in that year, just in the American Division (of My Lai fame), one fragging per week took place. Some military estimates are that fraggings occurred at five times the official rate, while officers of the Judge Advocate General Corps believed that only 10 percent of fraggings were reported. These figures do not include officers who were shot in the back by their men and listed as wounded or killed in action.

Most fraggings resulted in injuries, although “word of the deaths of officers will bring cheers at troop movies or in bivouacs of certain units.” The army admitted that it could not account for how 1,400 officers and noncommissioned officers died. This number, plus the official list of fragging deaths, has been accepted as the unacknowledged army estimate for officers killed by their men. It suggests that 20 to 25 percent–if not more–of all officers killed during the war were killed by enlisted men, not the “enemy.” This figure has no precedent in the history of war.

Soldiers put bounties on officers targeted for fragging. The money, usually between $100 and $1,000, was collected by subscription from among the enlisted men. It was a reward for the soldier who executed the collective decision. The highest bounty for an officer was $10,000, publicly offered by GI Says, a mimeographed bulletin put out in the 101st Airborne Division, for Col. W. Honeycutt, who had ordered the May 1969 attack on Hill 937. The hill had no strategic significance and was immediately abandoned when the battle ended. It became enshrined in GI folklore as Hamburger Hill, because of the 56 men killed and 420 wounded taking it. Despite several fragging attempts, Honeycutt escaped uninjured.

As Vietnam GI argued after Hamburger Hill, “Brass are calling this a tremendous victory. We call it a goddam butcher shop…If you want to die so some lifer can get a promotion, go right ahead. But if you think your life is worth something, you better get yourselves together. If you don’t take care of the lifers, they might damn well take care of you.”

Fraggings were occasionally called off. One lieutenant refused to obey an order to storm a hill during an operation in the Mekong Delta. “His first sergeant later told him that when his men heard him refuse that order, they removed a $350 bounty earlier placed on his head because they thought he was a ‘hard-liner.’”

The motive for most fraggings was not revenge, but to change battle conduct. For this reason, officers were usually warned prior to fraggings. First, a smoke grenade would be left near their beds. Those who did not respond would find a tear-gas grenade or a grenade pin on their bed as a gentle reminder. Finally, the lethal grenade was tossed into the bed of sleeping, inflexible officers. Officers understood the warnings and usually complied, becoming captive to the demands of their men. It was the most practical means of cracking army discipline. The units whose officers responded opted out of search-and-destroy missions.

An Army judge who presided over fragging trials called fragging “the troops’ way of controlling officers,” and added that it was “deadly effective.” He explained, “Captain Steinberg argues that once an officer is intimidated by even the threat of fragging he is useless to the military because he can no longer carry out orders essential to the functioning of the Army. Through intimidation by threats–verbal and written…virtually all officers and NCOs have to take into account the possibility of fragging before giving an order to the men under them.” The fear of fragging affected officers and NCOs far beyond those who were actually involved in fragging incidents.

Officers who survived fragging attempts could not tell which of their men had tried to murder them, or when the men might strike again. They lived in constant fear of future attempts at fragging by unknown soldiers. In Vietnam it was a truism that “everyone was the enemy”: for the lifers, every enlisted man was the enemy. “In parts of Vietnam fragging stirs more fear among officers and NCOs than does the war with ‘Charlie.’”

Counter-fragging by retaliating officers contributed to a war within the war. While 80 percent of fraggings were of officers and NCOs, 20 percent were of enlisted men, as officers sought to kill potential troublemakers or those whom they suspected of planning to frag them. In this civil war within the army, the military police were used to reinstate order. In October 1971, military police air assaulted the Praline mountain signal site to protect an officer who had been the target of repeated fragging attempts. The base was occupied for a week before command was restored.

Fragging undermined the ability of the Green Machine to function as a fighting force. By 1970, “many commanders no longer trusted Blacks or radical whites with weapons except on guard duty or in combat.” In the American Division, fragmentation grenades were not given to troops. In the 440 Signal Battalion, the colonel refused to distribute all arms. As a soldier at Cu Chi told the New York Times, “The American garrisons on the larger bases are virtually disarmed. The lifers have taken the weapons from us and put them under lock and key.” The U.S. army was slowly disarming its own men to prevent the weapons from being aimed at the main enemy: the lifers.

Peace from below–search and avoid

Mutiny and fraggings expressed the anger and bitterness that combat soldiers felt at being used as bait to kill Communists. It forced the troops to reassess who was the real enemy.

In a remarkable letter, 40 combat officers wrote to President Nixon in July 1970 to advise him that “the military, the leadership of this country–are perceived by many soldiers to be almost as much our enemy as the VC and the NVA.

After the 1970 invasion of Cambodia enlarged the war, fury and the demoralizing realization that nothing could stop the warmongers swept both the antiwar movement and the troops. The most popular helmet logo became “UUUU,” which meant “the unwilling, led by the unqualified, doing the unnecessary, for the ungrateful.” Peace, if it were to come, would have to be made by the troops themselves, instituted by an unofficial troop withdrawal ending search-and-destroy missions.

The form this peace from below took came to be called “search and avoid,” or “search and evade.” It became so extensive that “search and evade (meaning tacit avoidance of combat by units in the field) is now virtually a principle of war, vividly expressed by the GI phrase, ‘CYA’ (cover your ass) and get home!”

In search and avoid, patrols sent out into the field deliberately eluded potential clashes with the NLF. Night patrols, the most dangerous, would halt and take up positions a few yards beyond the defense perimeter, where the NLF would never come. By skirting potential conflicts, they hoped to make it clear to the NLF that their unit had established its own peace treaty.

Another frequent search-and-avoid tactic was to leave base camp, secure a safe area in the jungle and set up a perimeter-defense system in which to hole up for the time allotted for the mission. “Some units even took enemy weapons with them when they went out on such search-and-avoid missions so that upon return they could report a firefight and demonstrate evidence of enemy casualties for the body-count figures required by higher headquarters.”

The army was forced to accommodate what began to be called “the grunts’ cease-fire.” An American soldier from Cu Chi, quoted in the New York Times, said, “They have set up separate companies for men who refuse to go out into the field. It is no big thing to refuse to go. If a man is ordered to go to such and such a place, he no longer goes through the hassle of refusing; he just packs his shirt and goes to visit some buddies at another base camp.”

An observer at Pace, near the Cambodian front where a unilateral truce was widely enforced, reported, “The men agreed and passed the word to other platoons: nobody fires unless fired upon. As of about 1100 hours on October 10,1971, the men of Bravo Company, 11/12 First Cav Division, declared their own private cease-fire with the North Vietnamese.”

The NLF responded to the new situation. People’s Press, a GI paper, in its June 1971 issue claimed that NLF and NVA units were ordered not to open hostilities against U.S. troops wearing red bandanas or peace signs, unless first fired upon. Two months later, the first Vietnam veteran to visit Hanoi was given a copy of “an order to North Vietnamese troops not to shoot U.S. soldiers wearing antiwar symbols or carrying their rifles pointed down.” He reports its impact on “convincing me that I was on the side of the Vietnamese now.”

Colonel Heinl reported this:

That ‘search-and-evade’ has not gone unnoticed by the enemy is underscored by the Viet Cong delegation’s recent statement at the Paris Peace Talks that Communist units in Indochina have been ordered not to engage American units which do not molest them. The same statement boasted–not without foundation in fact–that American defectors are in the VC ranks.

Some officers joined, or led their men, in the unofficial cease-fire from below. A U.S. army colonel claimed:

I had influence over an entire province. I put my men to work helping with the harvest. They put up buildings. Once the NVA understood what I was doing, they eased up. I’m talking to you about a de facto truce, you understand. The war stopped in most of the province. It’s the kind of history that doesn’t get recorded. Few people even know it happened, and no one will ever admit that it happened.

Search and avoid, mutiny and fraggings were a brilliant success. Two years into the soldiers’ upsurge, in 1970, the number of U.S. combat deaths were down by more than 70 percent (to 3,946) from the 1968 high of more than 14,000. The revolt of the soldiers in order to survive and not to allow themselves to be victims could only succeed by a struggle prepared to use any means necessary to achieve peace from below.

The army revolt had all of the strengths and weaknesses of the 1960s radicalization of which it was a part. It was a courageous mass struggle from below. It relied upon no one but itself to win its battles.

The only organizing tools were the underground GI newspapers. But newspapers became a substitute for organization.

The hidden history of the 1960s proves that the American army can be split. But that requires the long, slow patient work of explanation, of education, of organization, and of agitation and action. The Vietnam revolt shows how rank-and-file soldiers can rise to the task.

May 2, 2012 Posted by aletho | Illegal Occupation, Militarism, Solidarity and Activism, Timeless or most popular | Pentagon, United States, United States Army, Vietnam, Vietnam War, William Westmoreland | 5 Comments

Afghans turn on occupiers

By Eric S. Margolis | Khaleej Times | 4 March 2012

Shock, incomprehension, fury. Americans are feeling these raw emotions as news keeps coming in of more attacks by Afghan government soldiers and officials on US and NATO troops. Six US troops were killed last week as a result of protests across Afghanistan following the burning of the Holy Quran by incredibly dim-witted American soldiers.

“Aren’t they supposed to be our allies? We are over there to save them! What outrageous ingratitude,” ask angry, confused Americans.

Angry Britons asked the same questions in 1857 when “sepoys,” individual mercenary soldiers of Britain’s Imperial Indian Army, then entire units rebelled and began attacking British military garrisons and their families. British history calls it the “Indian Mutiny.” Indians call it the “Great Rebellion” marking India’s first striving for freedom from the British Raj and the Indian vassal princes who so dutifully served it.

Britons were outraged by the “perfidy” and “treachery” of their Indian sepoys who were assumed to be totally loyal because they were fighting for the king’s shilling. Victorian Britain reeled from accounts of frightful massacres of Britons at places like Lucknow, Cawnpore, Delhi, and Calcutta’s infamous “black hole.”

As Karl Marx observed watching the ghastly events in India, western democracies cease practicing what they preach in their colonies. British forces in India, backed by loyal native units, mercilessly crushed the Indian rebels. Rebel ringleaders were tied to the mouths of cannon and blown to bits, or hanged en masse.

Today’s Afghanistan recalls Imperial India. Forces of the US-installed Kabul government, numbering about 310,000 men, are composed of Tajiks and Uzbeks from the north, some Shia Hazaras, and a hodgepodge of rogue Pashtun and mercenary groups. Ethnic Tajiks and Uzbeks served the Soviets when they occupied Afghanistan as well as the puppet Afghan Communist Party. Today, as then, Tajiks and Uzbeks form the core of government armed forces and secret police. They are the blood enemies of the majority Pashtun, who fill the ranks of Taleban and its allies in Afghanistan and neighbouring Pakistan.

But half the Afghan armed forces and police serve only to support their families. The Afghan economy under NATO’s rule is now so bad that even in Kabul, thousands are starving or dying from intense cold. Half of Afghans are unemployed and must seek work from the US-financed government.

But loyal they are not. While covering the 1980’s jihad against Soviet occupation, I saw everywhere that soldiers and officials supposedly loyal to the Communist Najibullah regime in Kabul kept in constant touch with the anti-Soviet mujahidin and reported all Soviet and government troops movements well in advance. The same thing occurs today in Afghanistan. Taleban know about most NATO troops operations before they leave their fortified bases. Among Afghans, the strongest bonds of loyalty are family, clan and tribal connections. They cut across all politics and ideology.

Afghans are a proud, prickly people who, as I often saw, take offense all too easily. Pashtuns are infamous for never forgetting an offense, real or imagines, and biding their time to strike back. This is precisely what has been happening in Afghanistan, where arrogant, culturally ignorant US and NATO ‘advisors’ – who are really modern versions of the British Raj’s “white officers leading native troops”- offend and outrage the combustible Afghans. Those who believe 20-year old American soldiers from the Hillbilly Ozarks can win the hearts and minds of Pashtun tribesmen are fools.

Proud Pashtun Afghans can take just so much from unloved, often detested foreign “infidels” advisors before exploding and exacting revenge. This also happened during the Soviet era. But some Soviet officers at least had more refined cultural sensibilities in dealing with Afghan. US-Afghan relations are not going to flowers when American troops call the Afghans “sand niggers” and “towel heads.” Many US GI’s hail from the deep south.

Many Afghans have just had enough of their foreign occupiers. The Americans have lost their Afghan War. As the Imperial British used to say: you can only rent Afghans for so long. One day they will turn and cut your throat.

Related articles

- Taliban infiltration very sophisticated: Afghan army (nation.com.pk)

March 4, 2012 Posted by aletho | Illegal Occupation, Militarism, Timeless or most popular | Afghanistan, British Raj, United States Army | 1 Comment

Featured Video

Panama Ransacked in 1989

or go to

Aletho News Archives – Video-Images

From the Archives

Hands off ‘our hemisphere’ or Venezuela pays the price: US Senator warns Russia

RT | February 13, 2019

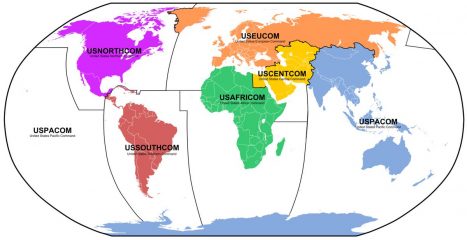

The US staked a claim on half the world, as Senate Armed Services Committee chair Jim Inhofe said Washington might have to intervene in Venezuela if Russia dares set up a military base not just there, but “in our hemisphere.”

“I think that it could happen,” Inhofe (R-Oklahoma) told a group of reporters on Tuesday. “You’ve got a guy down there that is killing everybody. You could have him put together a base that Russia would have on our hemisphere. And if those things happen, it may be to the point where we’ll have to intervene with troops and respond.”

Should Russia dare encroach on the US’ neck of the woods, Inhofe said: “we have to take whatever action necessary to stop them from doing that.” … continue

Blog Roll

-

Join 2,405 other subscribers

Visits Since December 2009

- 7,272,723 hits

Looking for something?

Archives

Calendar

Categories

Aletho News Civil Liberties Corruption Deception Economics Environmentalism Ethnic Cleansing, Racism, Zionism Fake News False Flag Terrorism Full Spectrum Dominance Illegal Occupation Mainstream Media, Warmongering Malthusian Ideology, Phony Scarcity Militarism Progressive Hypocrite Russophobia Science and Pseudo-Science Solidarity and Activism Subjugation - Torture Supremacism, Social Darwinism Timeless or most popular Video War Crimes Wars for IsraelTags

9/11 Afghanistan Africa al-Qaeda Australia BBC Benjamin Netanyahu Brazil Canada CDC Central Intelligence Agency China CIA CNN Covid-19 COVID-19 Vaccine Donald Trump Egypt European Union Facebook FBI FDA France Gaza Germany Google Hamas Hebron Hezbollah Hillary Clinton Human rights Hungary India Iran Iraq ISIS Israel Israeli settlement Japan Jerusalem Joe Biden Korea Latin America Lebanon Libya Middle East National Security Agency NATO New York Times North Korea NSA Obama Pakistan Palestine Poland Qatar Russia Sanctions against Iran Saudi Arabia Syria The Guardian Turkey Twitter UAE UK Ukraine United Nations United States USA Venezuela Washington Post West Bank WHO Yemen ZionismRecent Comments

seversonebcfb985d9 on Somaliland and the ‘Grea… John Edward Kendrick on Kidnapped By the Washington… aletho on Somaliland and the ‘Grea… John Edward Kendrick on Somaliland and the ‘Grea… aletho on Donald Trump, and Most America… John Edward Kendrick on Donald Trump, and Most America… aletho on The US Has Invaded Venezuela t… John Edward Kendrick on The US Has Invaded Venezuela t… papasha408 on The US Has Invaded Venezuela t… loongtip on Palestine advocates praise NYC… Bill Francis on Did Netanyahu just ask Trump f… Rod on How Intelligence, Politics, an…

Aletho News

Aletho News- Russia carries out three evacuation flights from Israel in under 24 hours

- 2016: The Year American Democracy Became “Post-Truth”

- Somaliland: Longtime Zionist colonisation target

- US hijacks fifth oil tanker in Caribbean waters as Washington tightens blockade on Venezuela

- From Industrial Power to Military Keynesianism: Germany’s Engineered Collapse

- Offshore wind turbines steal each other’s wind: yields greatly overestimated

- UK Expands Online Safety Act to Mandate Preemptive Scanning of Digital Communications

- Trump Pulls Plug on Ukraine’s Pentagon-Linked Bioweapons Web

- One Hundred People Killed in US Attack on Venezuela – Interior Minister

- The Year Ahead in Sino-American Relations

If Americans Knew

If Americans Knew- Israel says education in Gaza is not a critical activity – Not a ceasefire Day 91

- Israel is starving Gaza, ‘asphyxiating’ West Bank – Not a ceasefire Day 90

- Israel Targeted Churches, Mosques, and Markets during the Genocide.

- ‘We Saved the Child From Drowning’: In Gaza, Winter Storm Makes Displacement Even Deadlier

- Palestinian church committee urges churches worldwide to protect aid work in Gaza

- BlackNest: Inside Canary Mission’s Secret Web of Unlisted Sites

- Gaza staggers under 80% unemployment rate – Not a ceasefire Day 89

- Israel has detained Dr. Hussam Abu Safiya without charges for a year. Why has the New York Times refused to cover his case?

- Israel’s role in Trump’s attacks on Venezuela

- Shrinking Gaza: Israel moves Yellow Line again – Not a ceasefire Day 88

No Tricks Zone

No Tricks Zone- Berlin Blackout Shows Germany’s $5 Trillion Green Scheme Is “Left-Green Ideological Pipe Dream”

- Modeling Error In Estimating How Clouds Affect Climate Is 8700% Larger Than Alleged CO2 Forcing

- Berlin’s Terror-Blackout Enters 4th Day As Tens Of Thousands Suffer In Cold Without Heat!

- Expect Soon Another PIK Paper Claiming Warming Leads To Cold Snaps Over Europe

- New Study: Human CO2 Emissions Responsible For 1.57% Of Global Temperature Change Since 1750

- Welcome To 2026: Europe Laying Groundwork For Climate Science Censorship!

- New Study Finds A Higher Rate Of Global Warming From 1899-1940 Than From 1983-2024

- Meteorologist Dr. Ryan Maue Warns “Germany Won’t Make It” If Winter Turns Severe

- Merry Christmas Everybody!

- Two More New Studies Show The Southern Ocean And Antarctica Were Warmer In The 1970s

Contact:

atheonews (at) gmail.com

Disclaimer

This site is provided as a research and reference tool. Although we make every reasonable effort to ensure that the information and data provided at this site are useful, accurate, and current, we cannot guarantee that the information and data provided here will be error-free. By using this site, you assume all responsibility for and risk arising from your use of and reliance upon the contents of this site.

This site and the information available through it do not, and are not intended to constitute legal advice. Should you require legal advice, you should consult your own attorney.

Nothing within this site or linked to by this site constitutes investment advice or medical advice.

Materials accessible from or added to this site by third parties, such as comments posted, are strictly the responsibility of the third party who added such materials or made them accessible and we neither endorse nor undertake to control, monitor, edit or assume responsibility for any such third-party material.

The posting of stories, commentaries, reports, documents and links (embedded or otherwise) on this site does not in any way, shape or form, implied or otherwise, necessarily express or suggest endorsement or support of any of such posted material or parts therein.

The word “alleged” is deemed to occur before the word “fraud.” Since the rule of law still applies. To peasants, at least.

Fair Use

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more info go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

DMCA Contact

This is information for anyone that wishes to challenge our “fair use” of copyrighted material.

If you are a legal copyright holder or a designated agent for such and you believe that content residing on or accessible through our website infringes a copyright and falls outside the boundaries of “Fair Use”, please send a notice of infringement by contacting atheonews@gmail.com.

We will respond and take necessary action immediately.

If notice is given of an alleged copyright violation we will act expeditiously to remove or disable access to the material(s) in question.

All 3rd party material posted on this website is copyright the respective owners / authors. Aletho News makes no claim of copyright on such material.