French Polynesia to demand nearly $1bn from Paris over tests

RT | November 25, 2014

In an unprecedented move, French Polynesia, an overseas territory governed by France, is to ask Paris for nearly $1 billion in compensation for damage caused by nuclear weapons tests carried out by France in the South Pacific between 1966 and 1996.

The Assembly of French Polynesia has prepared a demand for $930 million (754,2 million euros) over “major pollution” caused by the 193 tests carried out by France for 30 years, La Dépêche de Tahiti reported. On top of this, the proposed resolution seeks an additional $132 million for the continued occupation of the Fangataufa and Mururoa atolls, used for nuclear testing.

The conservative Tahoera’a Huiraatira party committee has been acting independently of Polynesian President Edouard Fritch, who said he was “sorry” for the motion “written without consulting him,” local press reported.

Meanwhile, the text of the resolution, set for approval by the Assembly, highlights a “very poor situation of the atolls,” and a clean-up “impossible in the current state of scientific knowledge,” Tahiti Infos reported. They write that French Polynesia has been “too long sidelined” from decisions on “waste conservation and monitoring modes whatever their nature as well as the rehabilitation options of the atolls.”

On 24 August 1968, France conducted its first multi-stage thermonuclear test at Fangataufa atoll in the South Pacific Ocean, the so-called ‘Canopus’ test. With a 2.6 megaton yield, its explosive power was 200 times that of the Hiroshima bomb, according to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO).

France began its last series of nuclear tests in the South Pacific in 1995, breaking a three-year moratorium, provoking international protests and the boycott of French goods. It conducted its final nuclear test in January 1996 and then permanently dismantled its nuclear test sites. Later in that year, France signed the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT).

In 1996, in the wake of the nuclear testing, a $150 million annual payment was granted to French Polynesia, a territory of over 100 islands and atolls with its own government.

France, together with China, is not party to the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which bans nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, under water and outer space but not underground.

Last year it came to light that French nuclear tests carried out in the South Pacific had proved to be far more toxic than previously thought. According to declassified documents, seen by Le Parisien, plutonium fallout covered a much broader area than Paris had initially admitted, with Tahiti allegedly exposed to 500 times the maximum accepted levels of radiation.

According to the CTBTO, a study conducted between 2002 and 2005 of thyroid cancer sufferers in Tahiti, who had been diagnosed between 1984 and 2002, established a “significant statistical relationship” between cancer rates and exposure to radioactive fallout from French nuclear tests. Another survey carried out by an official French medical research body, Inserm, in 2006, also detected an increase in thyroid cancer among people who had been living within some 1,300 km of the nuclear tests conducted on the Polynesian atolls between 1969 and 1996.

In 2010, France pledged that veterans and survivors would be elegible for compensation, noting that this process would take time.

US Navy to kill, injure ‘thousands’ of whales, dolphins during drills – activists

RT | November 11, 2014

As the US Navy conducts war games off the coasts of California and Hawaii over the next four years, environmentalists are fighting back with legal action over concerns that hundreds, if not thousands, of marine animals will be injured or killed.

The Conservation Council for Hawaii has recently asked a judge to put an end to the naval exercises in the region on the grounds that they violate the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), the Washington Post reports. The group previously filed a lawsuit against the war games last year before the exercises began, arguing the drills should not have been approved in the first place.

At the center of the controversy are the lives and health of potentially millions of marine mammals, which can suffer hearing loss or damaged lungs from powerful sonar and death from underwater explosions.

The Council’s representatives in the lawsuit, including the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), argue that the use of sonar and explosives in the war games will kill too many blue whales, dolphins and seals to justify the training plans.

Environmentalists specifically point to the Navy’s own numbers in making their case. Back in 2013, the Navy projected that 155 marine mammals would be killed between 2014 and 2019 as a result of the war games. Thousands of animals would face permanent injuries, while almost 10 million would suffer temporary hearing loss or have their normal routines and behaviors disrupted.

“The more we look at the Navy’s activities, the more we’re finding the potential for harm,” said NRDC’s Michael Jasny to the Post.

For its part, the Navy has taken exception to the claims of advocates, saying they are misrepresenting the numbers. Navy spokesperson Kenneth Hess reiterated that the figures are not meant to depict one year’s worth of activity and also that they “represent worst-case scenarios.”

“Despite decades of the Navy conducting very similar activities in these same areas, there is no evidence of these types of impacts,” Hess said to the newspaper. He added that permits for these exercises “can only be issued if our activities will have no more than a negligible impact on marine mammal populations.”

Researchers who support the Navy’s position also argue that opponents are trying to gain attention by asserting all these sea-going animals will die.

However, environmental activists note that the Navy’s estimates go beyond the number of deaths permitted under the MMPA. Considering that is the case, they argue there is no evidence suggesting the Navy tried to scale back the potential damage after releasing its projections.

“No one is suggesting the Navy shouldn’t be allowed to do testing and training,” said Eearthjustice attorney David Henkin to the Post. “The question is whether they need every inch of the ocean … particularly biologically significant small refuges.”

So far, the US court system has sided with the Navy. In 2008, the Supreme Court ruled that environmental interests took a backseat to the military’s, but animal rights advocates are hoping that the link between sonar and animal health, as well as the Navy’s estimated fatalities, will help influence a different decision.

Inside the UN Resolution on Depleted Uranium

By JOHN LAFORGE | CounterPunch | November 6, 2014

On October 31, a new United Nations General Assembly First Committee resolution on depleted uranium (DU) weapons passed overwhelmingly. There were 143 states in favor, four against, and 26 abstentions. The measure calls for UN member states to provide assistance to countries contaminated by the weapons. The resolution also notes the need for health and environmental research on depleted uranium weapons in conflict situations.

This fifth UN resolution on the subject was fiercely opposed by four depleted uranium-shooting countries — Britain, the United States, France and Israel — who cast the only votes in opposition. The 26 states that abstained reportedly sought to avoid souring lucrative trade relationships with the four major shooters.

Uranium-238 — so-called “depleted” uranium — is waste material left in huge quantities by the nuclear weapons complex. It’s used in large caliber armor-piercing munitions and in armor plate on tanks. Toxic, radioactive dust and debris is dispersed when DU shells burn through targets, and its metallic fumes and dust poison water, soil and the food chain. DU has been linked to deadly health effects like Gulf War Syndrome among U.S. and allied troops, and birth abnormalities among populations in bombed areas. DU waste has caused radioactive contamination of large parts of Iraq, Bosnia, Kosovo and perhaps Afghanistan.

The measure explains that DU weapons are made of a “chemically and radiologically toxic heavy metal” [uranium-238], that after use “penetrator fragments, and jackets or casings can be found lying on the surface or buried at varying depth, leading to the potential contamination of air, soil, water and vegetation from depleted uranium residue.”

The main thrust of the latest UN resolution, “Encourages Member States in a position to do so to provide assistance to States affected by the use of arms and ammunition containing depleted uranium, in particular in identifying and managing contaminated sites and material.” The request is a veiled reference to the fact that investigators have been stymied in their study of uranium contamination in Iraq, because the Pentagon refuses to disclose maps of all the places it attacked with DU.

In the diplomatic confines of UN resolutions, individual countries are not named. Yet the world knows that up to 700 tons of DU munitions were blasted into Iraq and Kuwait by U.S. forces in 1991, and that U.S. warplanes fired another three tons into Bosnia in 1994 and 1995; ten tons into Kosovo in 1999, and approximately 170 tons into Iraq again in 2003.

The International Coalition to Ban Uranium Weapons (ICBUW.org), based in Manchester, England and representing over 160 civil society organizations worldwide, played a major part in seeing all five resolutions through the UN process and is working for a convention that would see the munitions outlawed. In October, ICBUW reported that the US military will again use DU weapons in Iraq in its assaults against ISIS “if it needs to”. The admission came in spite of Iraq’s summer 2014 recent call for a global ban on the weapons and assistance in clearing up the contamination left from bombardments in 1991 and 2003.

The new resolution relies heavily on the UN Environment Program (UNEP) which conducted radiation surveys of NATO bombing targets in the Balkans and Kosovo. It was a UNEP study in 2001 that forced the Pentagon to admit that its DU is spiked with plutonium. (Associated Press, Capital Times, Feb. 3, 2001: “But now the Pentagon says shells used in the 1999 Kosovo conflict were tainted with traces of plutonium, neptunium and americium — byproducts of nuclear reactors that are much more radioactive than depleted uranium.”)

The resolution’s significant fourth paragraph notes in part: “… major scientific uncertainties persisted regarding the long-term environmental impacts of depleted uranium, particularly with respect to long-term groundwater contamination. Because of these scientific uncertainties, UNEP called for a precautionary approach to the use of depleted uranium, and recommended that action be taken to clean up and decontaminate the polluted sites. It also called for awareness-raising among local populations and future monitoring.”

The “precautionary principle” holds that risky activities or substances should be shunned and discouraged unless they can be proved safe. Of course, instead of adopting precaution, the Pentagon denies that DU can be linked to health problems.

John LaForge works for Nukewatch and lives on the Plowshares Land Trust near Luck, Wisc.

Fukushima dismantling crew removes 400 tons of spent fuel from crippled reactor

RT | November 5, 2014

The first of four sets of spent nuclear fuel rods has been removed from a damaged reactor building at Japan’s Fukushima power plant, scoring a major success in an effort to dismantle the quake and tsunami-wrecked facility.

The 1,331 spent fuel rod assemblies weighting some 400 tons have been recovered from the upper levels of the Reactor 4 building after a year-long operation, a spokeswoman for Fukushima operator TEPCO reported on Wednesday. The last 11 assemblies were removed on Tuesday.

The recovered assemblies were placed in a storage pool at ground level of the plant, the company said.

TEPCO is still to remove 180 rod assemblies that haven’t been used at the reactor and are considered less dangerous because, unlike the spent fuel, they have not been irradiated. Some of the unused rod assemblies are already in the new storage pool. The task is expected to be completed by the end of the year.

Three other reactor buildings are holding almost 1,400 fuel assemblies in storage pools, and they must be recovered too. The operation started with Reactor 4 because it was damaged most in the March 2011 disaster due to a series of hydrogen explosions inside the building and is in danger of collapsing.

The operations at Reactors 1, 2 and 3 would be more difficult, because unlike Reactor 4 they were operational at the time of the disaster and experienced meltdowns, resulting in higher levels of radioactive contamination.

TEPCO plans to start removing fuel from Reactor 1 in 2019, two years later than originally planned. At the moment preparations for the removal are underway, with the operator recently removing the canopy over the building to allow debris removal.

The utility is surveying the interior of the Reactor 2 building and removing debris at the Reactor 3 using remote-controlled robots.

After dealing with the fuel, the most difficult task may be addressed – the recovery of reactor cores. The unprecedented operation may start in 2025, five years after initially planned.

No more time to wait for a nuclear weapons ban

International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons | Statement to the UN First Committee | October 28, 2014

Nuclear disarmament has for too long been about waiting. Waiting for nuclear-armed states to fulfill their obligations. Waiting for the so-called “conditions” to be right for disarmament.

While we wait, we do not get closer to the elimination of nuclear weapons or to a more secure world. While we wait, the risks of the use of nuclear weapons remain or even increase. While we wait, the catastrophic and overwhelming consequences of such use do not diminish.

We do not have time to wait.

The conferences on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons hosted by Norway and Mexico have clearly explained and documented these consequences.

Physicians, physicists, climate scientists, humanitarian agencies, and survivors have all presented alarming evidence about the effects of nuclear weapons.

This evidence has shown that a single nuclear weapon can destroy an entire city, inflicting massive numbers of instantaneous casualties.

This evidence has shown that acute radiation injuries kill people in a matter of minutes, days, or weeks; and that radiation-caused cancers and other illnesses continue to kill for years among those directly exposed and across generations.

This evidence has shown that the use of even a small fraction of existing nuclear arsenals would cause environmental devastation, including disruption of the global climate and agricultural production.

This evidence cannot be ignored.

We know that the only way to ensure these consequences will never occur is to prevent the use of nuclear weapons. And the only way to do that is to eliminate them entirely. The General Assembly, NPT states parties, the International Court of Justice, the overwhelming majority of states that belong to nuclear-weapon-free zones, and civil society have all said this repeatedly. That part of the debate is over.

We don’t have time to wait. States are in fact legally bound not to wait. Every state party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty is committed to pursuing effective measures for nuclear disarmament.

Most importantly, we do not have to wait.

While the nuclear-armed states modernise their arsenals and refuse to engage in multilateral negotiations for nuclear disarmament as they are obliged to do, there is at least one effective measure that the rest of the world can take.

That is to prohibit nuclear weapons through a legally-binding instrument.

This is not a radical proposal. Indiscriminate weapons get banned. It is what we do as human society in the interests of protecting ourselves. We have done it before with other weapon systems, including biological and chemical weapons. A treaty banning nuclear weapons would complete the set of

prohibitions against WMD.

This should not be a controversial proposal. An international prohibition is merely the logical outcome of an examination of the risks and consequences of nuclear weapons detonation. It is complementary to existing international law governing nuclear weapons.

This is a meaningful proposal. It could have a variety of effects on the policy and practice of states. It could establish a comprehensive set of prohibitions and provide a framework under which the elimination of nuclear weapons can be pursued.

This is a feasible, achievable proposal. It can be negotiated in the near-term, and have normative and practical impacts for the long-term.

Naturally, as we get closer to beginning a diplomatic process, thoughts will turn to how and where such a treaty should be negotiated.

ICAN has no fixed view on this except that effective processes that have meaningful results tend to be based on some important principles of multilateralism. Negotiations must be inclusive, democratic, and involve civil society and international organizations.

A crucial foundation for our confidence in this idea is the conviction that such a treaty can and should be negotiated by those states ready to do so, even if the states with nuclear weapons oppose it and decide not to participate. A few recalcitrant states should not be able to block a successful outcome. It would be better for all states to participate and to move towards prohibition and elimination without delay. But this seems unlikely at the present time.

While we must keep working towards that goal with absolute determination, we believe states should put a prohibition in place now.

To the nuclear-armed states that see this as a hostile idea: it is not. You have applauded groups of states for adopting nuclear-weapon-free zones in their regions. Globalising this prohibition on nuclear weapons will give increased political and legal space for you to pursue elimination. All of you have registered your commitment to a nuclear-free world. A prohibition of nuclear weapons is an important part of the process to achieve that universal goal.

To the states in alliances with nuclear-armed states that are concerned such a treaty would be inconsistent with existing commitments: it would not be. All states have agreed that nuclear weapons should be eliminated. No security alliances have ever crumbled because a weapon system was outlawed and eliminated. Any states that consider humanitarian action a priority should understand that a ban treaty would be consistent with their existing obligations and principles.

To the states that have already foresworn nuclear weapons through the NPT and nuclear-weapon-free zones, and that might baulk at the idea of taking on more of the burden for nuclear disarmament: this ban treaty will not be a burden. It will reinforce the stigma against nuclear weapons. It will undermine their purported value. It will further erode any misplaced perceptions that these weapons of mass destruction confer symbolic power and prestige. It will make global the commitments you have already made regionally. It will give you an opportunity to take charge, for nuclear disarmament is the responsibility and right of everyone. Finally, it will have normative and practical impacts that will facilitate elimination. We welcome the opportunity to consider this approach with you. As Kenya said earlier this month, discussions about this should not cause anxiety.

A window of opportunity is now open to take an important next step towards the elimination of nuclear weapons. We should seize this opportunity before it closes. The conferences in Oslo and Nayarit have helped us see nuclear weapons as the devastating and inhumane weapons they are. We’re confident that the Vienna conference in December will reinforce that humanitarian perspective.

It is clear to us that the logical conclusion of these evidence-based gatherings is to begin a diplomatic process to prohibit nuclear weapons through a legally binding instrument.

This will take courage. We have confidence that the overwhelming majority of states will join this process. And we look forward to accompanying you along the road to a treaty banning nuclear weapons.

International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) represents more than 360 partner organizations in 93 countries.

How does the Gates Foundation spend its money to feed the world?

GRAIN | November 4, 2014

“Listening to farmers and addressing their specific needs. We talk to farmers about the crops they want to grow and eat, as well as the unique challenges they face. We partner with organizations that understand and are equipped to address these challenges, and we invest in research to identify relevant and affordable solutions that farmers want and will use.” – First guiding principle of the Gates Foundation’s work on agriculture.1

At some point in June this year, the total amount given as grants to food and agriculture projects by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation surpassed the US$3 billion mark. It marked quite a milestone. From nowhere on the agricultural scene less than a decade ago, the Gates Foundation has emerged as one of the world’s major donors to agricultural research and development.

The Gates Foundation is arguably the biggest philanthropic venture ever. It currently holds a $40 billion endowment, made up mostly of contributions from Gates and his billionaire friend Warren Buffet. The foundation has over 1,200 staff, and has given over $30 billion in grants since its inception in 2000, $3.6 billion in 2013 alone.2 Most of the grants go to global health programmes and educational work in the US, traditionally the foundation’s priority areas. But in 2006-2007, the foundation massively expanded its funding for agriculture, with the launch of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) and a series of large grants to the international agricultural research system (CGIAR). In 2007, it spent over half a billion dollars on agricultural projects and has maintained funding at around this level. The vast majority of the foundation’s agricultural grants focus on Africa.

Spending so much money gives the foundation significant influence over agricultural research and development agendas. As the weight of the foundation’s overall focus on technology and private sector partnerships has begun to be felt in the global agriculture arena, it has raised opposition and controversy, particularly around its work in Africa. Critics say that the Gates Foundation is promoting an imported model of industrial agriculture based on the high-tech seeds and chemicals sold by US corporations. They say the foundation is fixated on the work of scientists in centralised labs and that it chooses to ignore the knowledge and biodiversity that Africa’s small farmers have developed and maintained over generations. Some also charge that the Gates Foundation is using its money to impose a policy agenda on Africa, accusing the foundation of direct intervention on highly controversial issues like seed laws and GMOs.

GRAIN looked through the foundation’s publicly available financial records to see if the actual flows of money support these critiques. We combed through all the grants for agriculture that the Gates Foundation gave between 2003 and September 2014.3 We then organised the grant recipients into major groupings (see table 2) and constructed a database, which can be downloaded here.4

Here are some of the conclusions we were able to draw from the data.

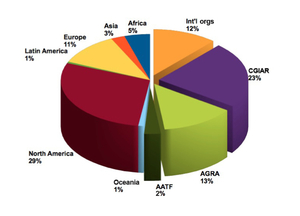

1. The Gates Foundation fights hunger in the South by giving money to the North.

Graph 1 and Table 1 give the overall picture. Roughly half of the foundation’s grants for agriculture went to four big groupings: the CGIAR’s global agriculture research network, international organisations (World Bank, UN agencies, etc.), AGRA (set up by Gates itself) and the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF). The other half ended up with hundreds of different research, development and policy organisations across the world. Of this last group, over 80% of the grants were given to organisations in the US and Europe, 10% went to groups in Africa, and the remainder elsewhere. Table 2 lists the top 10 countries where Gates grantees are located and the amounts they received, highlighting some of the main grantees. By far the main recipient country is Gates’s own home country, the US, followed by the UK, Germany and the Netherlands.

When it comes to agricultural grants by the foundation to universities and national research centres across the world, 79% went to grantees in the US and Europe, and a meagre 12% to recipients in Africa.

The North-South divide is most shocking, however, when we look at the NGOs that the Gates Foundation supports. One would assume that a significant portion of the frontline work that the foundation funds in Africa would be carried out by organisations based there. But of the $669 million that the Gates Foundation has granted to non-governmental organisations for agricultural work, over three quarters has gone to organisations based in the US. Africa-based NGOs get a meagre 4% of the overall agriculture-related grants to NGOs.

2. The Gates Foundation gives to scientists, not farmers

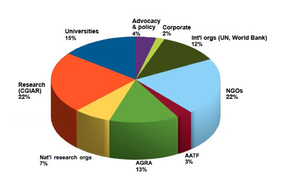

As can be seen in Graph 2, the single biggest recipient of grants from the Gates Foundation is the CGIAR, a consortium of 15 international agricultural research centres. In the 1960s and 70s, these centres were responsible for the development and spread of a controversial Green Revolution model of agriculture in parts of Asia and Latin America which focused on the mass distribution of a few varieties of seeds that could produce high yields – with the generous application of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Efforts to implement the same model in Africa failed and, globally, the CGIAR lost relevance as corporations like Syngenta and Monsanto took control over seed markets. Money from the Gates Foundation is providing CGIAR and its Green Revolution model a new lease on life, this time in direct partnership with seed and pesticide companies.5

Click to enlarge – Graph 2: the Gates Foundation’s $3 billion pie (agriculture grants, by type of organisation).

The CGIAR centres have received over $720 million from Gates since 2003. During the same period, another $678 million went to universities and national research centres across the world – over three-quarters of them in the US and Europe – for research and development of specific technologies, such as crop varieties and breeding techniques.

The Gates Foundation’s support for AGRA and the AATF is tightly linked to this research agenda. These organisations seek, in different ways, to facilitate research by the CGIAR and other research programmes supported by the Gates Foundation and to ensure that the technologies that come out of the labs get into farmers’ fields. AGRA trains farmers on how to use the technologies, and even organises them into groups to better access the technologies, but it does not support farmers in building up their own seed systems or in doing their own research.6

We could find no evidence of any support from the Gates Foundation for programmes of research or technology development carried out by farmers or based on farmers’ knowledge, despite the multitude of such initiatives that exist across the continent. (African farmers, after all, do continue to supply an estimated 90% of the seed used on the continent!) The foundation has consistently chosen to put its money into top down structures of knowledge generation and flow, where farmers’ are mere recipients of the technologies developed in labs and sold to them by companies.

3. The Gates Foundation buys political influence

Does the Gates Foundation use its money to tell African governments what to do? Not directly. The Gates Foundation set up the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa in 2006 and has supported it with $414 million since then. It holds two seats on the Alliance’s board and describes it as the “African face and voice for our work”.7

AGRA, like the Gates Foundation, provides grants to research programmes. It also funds initiatives and agribusiness companies operating in Africa to develop private markets for seeds and fertilisers through support to “agro-dealers” (see box on Malawi). An important component of its work, however, is shaping policy.

AGRA intervenes directly in the formulation and revision of agricultural policies and regulations in Africa on such issues as land and seeds. It does so through national “policy action nodes” of experts, selected by AGRA, that work to advance particular policy changes. For example, in Ghana, AGRA’s Seed Policy Action Node drafted revisions to the country’s national seed policy and submitted it to the government. The Ghana Food Sovereignty Network has been fiercely battling such policies since the government put them forward. In Mozambique, AGRA’s Seed Policy Action Node drafted plant variety protection regulations in 2013, and in Tanzania it reviewed national seed policies and presented a study on the demand for certified seeds. Also in Tanzania, its Land Policy Action Node is involved in revising the Village Land Act as well as “reviewing laws governing land titling at the district level and working closely with district officials to develop guidelines for formulation of by-laws.”8

The African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF) is another Gates Foundation supported organisation that straddles the technology and policy arenas. Since 2008, it has received $95 million from the Gates Foundation, which it used to to support the development and distribution of hybrid maize and rice varieties. But it also uses funds from the Gates Foundation to “positively change public perceptions” about GMOs and to lobby for regulatory changes that will increase the adoption of GM products in Africa.9

In a similar vein, the Gates Foundation provides Harvard University University with funds to promote discussion of biotechnology in Africa, Michigan University with a grant to set up a centre to help African policymakers decide on how best to use biotechnology, and Cornell University with funds to create a global “agricultural communications platform” so that people better understand science-based agricultural technologies, with AATF as a main partner.

Gates & AGRA in Malawi: organising the agro-dealers

One of AGRA’s core programmes in Africa is the establishment of “agro-dealer” networks: small, private stockists who sell chemicals and seeds to farmers. In Malawi, AGRA provided a $4.3 million grant for the Malawi Agro-dealer Strengthening Programme (MASP) to supply hybrid maize seeds and chemical pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers.

The main supplier to the agro-dealers in Malawi has been Monsanto, responsible for 67% of all inputs. A Monsanto country manager disclosed that all of Monsanto’s sales of seeds and herbicides in Malawi are made through AGRA’s agro-dealer network.

“Agro-dealers… act as vessels for promoting input suppliers’ products,” says one MASP project document. Another states: “supply companies have expressed their appreciation for field days because MASP trained agro-dealers are helping them promote their products in the very remotest areas of Malawi.” Training the agro-dealers on product knowledge is carried out by the corporate suppliers of the products themselves. In addition, these agro-dealers are increasingly the source of farming advice to small farmers, and an alternative to the government’s agricultural extension service.

A project evaluation report states that 44% of the agro-dealers in the programme were providing extension services. According to the World Bank: “The agro-dealers have… become the most important extension nodes for the rural poor… A new form of private sector driven extension system is emerging in these countries.” The agro-dealer project in Malawi has been implemented by CNFA, a US-based organisation funded by the Gates Foundation, USAID and DFID, and its local affiliate the Rural Market Development Trust (RUMARK), whose trustees include four seed and chemical suppliers: Monsanto, SeedCo, Farmers World and Farmers Association.

Listening to farmers?

“Listening to farmers and addressing their specific needs” is the first guiding principle of the Gates Foundation’s work on agriculture.10 But it is hard to listen to someone when you cannot hear them. Small farmers in Africa do not participate in the spaces where the agendas are set for the agricultural research institutions, NGOs or initiatives, like AGRA, that the Gates Foundation supports. These spaces are dominated by foundation reps, high-level politicians, business executives, and scientists.

Listening to someone, if it has any real significance, should also include the intent to learn. But nowhere in the programmes funded by the Gates Foundation is there any indication that it believes that Africa’s small farmers have anything to teach, that they have anything to contribute to research, development and policy agendas. The continent’s farmers are always cast as the recipients, the consumers of knowledge and technology from others. In practice, the foundation’s first guiding principle appears to be a marketing exercise to sell its technologies to farmers. In that, it looks, not surprisingly, a lot like Microsoft. … Full article with tables and notes

Japan to reopen 1st nuclear plant after Fukushima disaster – despite volcano risks

RT | October 28, 2014

A local council has voted to re-open the Sendai Nuclear Power Plant on the outermost western coast of Japan, despite local opposition and meteorologists’ warnings, following tremors in a nearby volcano.

Nineteen out of 26 members of the city council of Satsumasendai approved the reopening that is scheduled to take place from early 2015. Like all of Japan’s 48 functional reactors, Sendai’s 890 MW generators were mothballed in the months following the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

Satsumasendai, a town of 100,000 people, relies heavily on state subsidies and jobs, which are dependent on the continuing operation of the plant.

But other towns, located within sight of the plant, do not reap the same benefits, yet say they are being exposed to the same risks. A survey conducted by the local Minami-Nippon Shimbun newspaper earlier this year said that overall, 60 percent of those in the region were in favor of Sendai staying shut. In Ichikikushikino, a 30,000-strong community just 5 kilometers away, more than half of the population signed a petition opposing the restart. Fewer than half of the major businesses in the region reported that they backed a reopening, despite potential economic benefits.

Regional governor Yuichiro Ito has waved away the objections, insisting that only the city in which the plant is located is entitled to make the decision.

While most fears have centered around a lack of transparency and inadequate evacuation plans, Sendai is also located near the volcanically active Kirishima mountain range. Mount Ioyama, located just 65 kilometers away from the plant, has been experiencing tremors in recent weeks, prompting the Meteorological Agency to issue a warning. The government’s nuclear agency has dismissed volcanic risks over Sendai’s lifetime as “negligible,” however.

Mount Ioyama (image from blogs.yahoo.co.jp)

Satsumasendai’s Mayor Hideo Iwakiri welcomed the reopening, but said at the ensuing press conference that it would fall upon the government to ensure a repeat of the accident that damaged Fukushima, an outdated facility subject to loose oversight, is impossible.

September’s decision to initiate the return Japan’s nuclear capacity back online was taken by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who endorses nuclear production in the country, but has delegated the controversial call on reopening to local councils. Sendai was chosen after becoming the first plant to officially fulfill the government’s new stricter safety rules. It may also have been picked due to its geographical remoteness, and distance from the 2011 disaster area.

The primary reason for Abe’s nuclear drive been the expense in replacing the lost energy that constituted 30 percent of the country’s consumption, which the government says cost Japan an extra $35 billion last year. Japanese consumers have seen their energy bills climb by 20 percent since the disaster as a result.

But another concern remains the state of the country’s aging nuclear plants, which will cost $12 billion to upgrade. Meanwhile plans to build modern nuclear reactors – which were supposed to be responsible for half of the country’s nuclear power by 2030, according to previous government energy plans – have predictably been shelved in the wake of the disaster.

Fukushima dome removal suspended

The painfully slow and calamitous decommissioning of the Fukushima Daiichi plant, in the northeast of the country, had to be halted yet again Tuesday, after the removal of the temporary dome over the damaged Reactor 1 was interrupted by severe winds.

The canopy needs to be taken off so that the radioactive reactor rods, which have been contaminating the soil and water around the plant, can be placed in storage.

But as workers attempted to lift a section of the plastic dome to decontaminate the air inside, a segment of the cover up to six feet was blown off by a severe gust of wind.

Tokyo Electric Power Company, TEPCO, the operator of the shuttered plant, says that the incident has not impacted radiation levels, and hopes to resume operations as soon as possible.