Honduras: Expanding Palm Oil Empires In The Name Of ‘Green Energy’ And “Sustainable Development”

Written by Rights Action, Rainforest Rescue, Biofuelwatch, and Food First | August 6, 2013

From 6th-8th August, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is holding its 4th Latin American Conference on so-called sustainable palm oil in Honduras [1]. Environmental and social campaigners have been shocked to learn that one event sponsor is the palm oil company Dinant Corporation, owned and controlled by Miguel Facusse, the largest landowner in Honduras. They are calling on World Wildlife Fund WWF and three other organisations to withdraw from and denounce the conference being held in Honduras due to the Dinant’s sponsorship of the event and the serious human rights implications [2].

Mr. Facusse was a key supporter and beneficiary of the June 2009 military coup in Honduras [3], has been associated with narco-trafficking [4], and, along with other large oil palm growers, has been linked to the targeted killing of more than 88 members and supporters of peasant organisations since June 2009 in the Aguan Valley [5], one of the main palm oil producing regions in Honduras.

Annie Bird from Rights Action states: “By holding its conference in Honduras and by allowing Dinant Corporation to sponsor the event and hold a stall, the RSPO is turning a blind eye to systemic and severe human rights abuses, including forced evictions of entire communities and over 88 killings for which palm oil companies, especially Dinant, are responsible. The RSPO Conference serves to reinforce the impunity with which the large-scale palm producers operate.”

RSPO is overwhelmingly dominated by the interests of large corporations like Nestlé, Rabobank and Unilever—all linked to cases of “land grabbing” in Asia, Latin America and Africa.” [6]

According to Tanya Kerssen, Research Coordinator for Food First, “The case of Dinant is emblematic of how large, elite-controlled companies use palm oil to expand their control over land and other resources. The RSPO is merely window dressing for this continued corporate expansion, which—whether classed as ‘sustainable’ or not—necessarily means the replacement of forests, biodiversity and food production with a large-scale monoculture crop for biofuel and unhealthy edible oils.” [7]

Guadalupe Rodriguez from Rainforest Rescue adds: “WWF and the three other organisations involved in this RSPO conference must pull out of and denounce this process. They must not, however indirectly, associate themselves with palm oil businessmen involved in repressing, evicting and killing peasants in Honduras’s Aguan Valley.”

The European Commission considers all biofuels from RSPO-certified palm oil to be sustainable and thus eligible for government support [8]. This is despite growing evidence by a large number of organisations, which shows that the RSPO has not been enforcing its own standards on its member companies and cannot guarantee environmental or social sustainability of palm oil [9].

Almuth Ernsting from Biofuelwatch states: “The RSPO Secretariat’s decision to hold a conference in Honduras and allow Dinant Corporation to contribute sponsorship and hold a stall further undermines any pretence that the RSPO’s aim is to make palm oil sustainable. Far from addressing any of the most serious impacts of palm oil production, the RSPO continues to serve as an instrument of greenwashing for the industry”.

NOTES

[1] The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil is a stakeholder forum which provides voluntary certification for palm oil. The great majority of RSPO members represent industry interests. (Conference website: http://rspo2013.com/)

[2] See http://rightsaction.org/action-content/open-letter-world-wildlife-fund-solidaridad-network-snv-netherlands-development for an Open Letter to WWF, Solidaridad, SNV Netherlands Development Organisation and Forest Ethics on this issue.

[3] In June 2009, the democratically elected Honduran government of Manuel Zelaya was overthrown by a military coup. Manuel Zelaya’s government had begun listening to and acting on the demands of peasant organisations for land reform, including in the Aguan Valley region. The land reform process was ended by the military rulers after the coup. Since then, Dinant Corporation and their armed security forces have been collaborating with military forces and police forces in repressing local communities who have been trying to reclaim land controlled by Dinant. See for example: http://www.enca.org.uk/documents/ENCA56_Sep_2012.pdf .

[4] Published Wikileaks Cables revealed that the US embassy in Honduras has had evidence linking Miguel Facusse to drug trafficking since at least 2004 and that several aeroplanes with drugs have landed on his private property. See http://www.thenation.com/article/164120/wikileaks-honduras-us-linked-brutal-businessman#

[5] For a report by Rights Action about killings and other human rights abuses in the Aguan Valley, see http://rightsaction.org/sites/default/files/Rpt_130220_Aguan_Final.pdf .

[6] See, for example: “The bloody products of the house of Unilever” Rainforest Rescue, 2011. https://www.rainforest-rescue.org/mailalert/747/the-bloody-products-from-the-house-of-unilever

[7] For more on the link between palm oil expansion and corporate control, see Kerssen, Tanya. Grabbing Power: The New Struggles for Land, Food and Democracy in Northern Honduras. Food First Books, 2013.

[8] See http://www.rspo.org/news_details.php?nid=137

[9] Previously, over 250 organisations condemned the RSPO for ‘greenwashing’ of palm oil: http://www.biofuelwatch.org.uk/2008/rspo-declaration-english/ . More recently, the RSPO has been denounced for example by Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth; http://www.biofuelwatch.org.uk/2008/rspo-declaration-english/

Honduras: Army Kills Indigenous Leader at Dam Protest

Weekly News Update on the Americas | July 23, 2013

Tomás García Domínguez, an indigenous leader, was shot dead on July 15 in Intibucá department in western Honduras during a demonstration at the headquarters for the Agua Zarca hydroelectric project. Four other protesters were wounded, including García’s son, 17-year-old Allan García Domínguez, who was hospitalized in serious condition with a bullet in his lung. According to Civic Council of Grassroots and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH) leader Berta Cáceres, the demonstration was peaceful, but “without saying one word the army opened fire against our companions, sending bullets into the bodies of Tomás García and his son, in the presence of police that remained paralyzed and did nothing to prevent it.” A press release from the two companies constructing the dam—the Honduran company Desarrollos Energéticos S.A. (DESA) and the Chinese state enterprise SINOHYDRO—blamed the protesters and claimed the demonstration “included the destruction of installations, vehicles and personal property and direct aggression against the physical integrity of personnel.”

The protesters were from the Lenca group, the country’s largest indigenous ethnicity; Tomás García was a member of the Indigenous Lenca Council and of the COPINH. The Lenca communities near the Agua Zarca dam had been protesting the project for 106 days as of July 15 and had been subjected to harassment on previous occasions. Soldiers from the First Battalion of Engineers, the same unit that allegedly killed García, arrested Berta Cáceres and another COPINH member on May 24 after the two activists had visited Lenca communities resisting the dam [see Update #1181]. According to the COPINH, cars belonging to DESA were seen on July 12 going to the community of Unión, where there were reportedly meetings with murderers well known in the area, possibly with the intention of pressuring and intimidating dam opponents. (Adital (Brazil) 7/16/13; Indian Country Today 7/20/13)

Honduras: Judge Suspends Case Against Indigenous Leader

Weekly News Update on the Americas | June 23, 2013

After an eight-hour hearing on June 13, a court in Santa Bárbara, the capital of the western Honduran department of the same name, suspended a legal action against indigenous leader Berta Isabel Cáceres Flores for the alleged illegal possession of a weapon. According to Cáceres’ lawyer, Marcelino Martínez, the court found that there was not enough evidence to proceed with the case. Cáceres, who coordinates the Civic Council of Grassroots and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), is now free to travel out of the country, although the case could still be reopened. Representatives from some 40 organizations came to the city on June 13 in an expression of solidarity with the activist.

Cáceres was arrested along with COPINH radio communicator Tómas Gómez Membreño on May 24 when a group of about 20 soldiers stopped their vehicle and claimed to find a pistol under a car seat. Cáceres and Gómez Membreño had been visiting Lenca communities that were protesting the Agua Zarca hydroelectric project. The leader of the military patrol, First Battalion of Engineers commander Col. Milton Amaya, explicitly linked the arrests to the activists’ political work: the Honduran online publication Proceso Digital reported that Amaya “accused Cáceres of going around haranguing indigenous residents of a border region between Santa Bárbara and Intibucá known as Río Blanco so that they would oppose the building of the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam.”

According to SOA Watch—a US-based group that monitors the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC), formerly the US Army School of the Americas (SOA)—Amaya has studied at the school on two occasions. (Proceso Digital 5/26/13; Adital (Brazil) 6/14/13; Kaos en la Red 6/14/13 from COPINH, Radio Mundo Real, Honduras Libre, Derechos Humanos; SOA Watch 6/21/13)

Related articles

- US senators question aid to Honduras, citing extrajudicial killings (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- Honduras: Three Farmers Killed During Land Eviction (alethonews.wordpress.com)

State propaganda on NPR’s “Morning Edition”

By Justin Doolittle | Crimethink | June 12, 2013

On Wednesday’s episode of “Morning Edition” on NPR, a segment was devoted to exploring the extreme violence that has engulfed Honduras in recent years. Indeed, if measured by per capita murder rate, Honduras is now the most dangerous in the country in the world. There are many reasons why Honduran civil society has broken down like this, but let’s suspend that discussion for the moment in order to focus on one particular aspect of this story on NPR that was quite revealing.

At one point in the segment, Carrie Kahn, the NPR correspondent reporting from Honduras, said the following:

Last year, the U.S. Congress held up funding to Honduras over concerns of alleged human rights abuses and corruption, particularly in the Honduran police force. Part of the funds are still on hold.

This is an astonishing statement for someone who purports to be a journalist. Unless Ms. Kahn has psychic powers, she cannot know why the U.S. Congress held up funding to Honduras. She can only know why Congress said it was holding up funding to Honduras. There is often a profound difference between why politicians say they are implementing policy X and why they are actually doing it. As you might have heard, politicians are occasionally dishonest and insincere, and their decisions are informed by a number of factors that have nothing to do with their personal beliefs. For a journalist, someone who is supposed to adversarially cover politicians and express skepticism at everything they say, this kind of blind faith is inexcusable.

The problem, though, is that Ms. Kahn’s statement is actually quite a bit worse than that. Even if she had said, “the U.S. Congress held up funding to Honduras over what it claimed were concerns of alleged human rights abuses and corruption,” instead of just mindlessly repeating what the government claimed, that would still be wildly insufficient for any journalist who takes her profession even the slightest bit seriously. Why? Because the United States government provably does not base its decisions on allocating foreign aid on “concerns about human rights and corruption.” For decades, the U.S. has provided aid to some of the most repressive and corrupt governments on Earth. Going down the list would be trivial, but, for the sake of comparison, let’s stay relatively close by and just look at Colombia. The U.S. government ships hundreds of millions of dollars to the Colombian government every year; in FY 2012, $443 million was provided, making Colombia the leading recipient of U.S. aid in the hemisphere.

In a strange twist, though, Colombia is also widely considered to be the most repressive violator of human rights in the hemisphere, and corruption there is rampant. This is quite a conundrum. Ms. Kahn tells us that the U.S. withheld aid from Honduras “over concerns of alleged human rights abuses and corruption.” But the U.S. evidently has no such “concerns” in Colombia and continues to send hundreds of millions of dollars in annual aid. One is almost tempted to conclude that the U.S. government makes these decisions based not on noble and selfless “concerns” about human rights and corruption, but, rather, on what it perceives to be U.S. interests.

Ms. Kahn must know that the government claim she dutifully parroted is transparently fraudulent and, in fact, downright comical. She cannot be a working journalist and not know this. Presumably, she follows the news, she is knowledgeable regarding basic facts about U.S. aid, and she knows that the U.S. has always cheerfully sent aid to brutal regimes around the world. She’s not a wide-eyed poly-sci 101 student who is shocked to find out that U.S. government decisions are not invariably and solely based on considerations of Good and Evil. Ms. Kahn is a highly educated reporter, and she obviously does know these things, but the culture of obedience and submissiveness in American journalism is so profound that she probably doesn’t even consciously realize that she’s serving state power instead of doing journalism. The U.S. government told her that aid is being withheld to Honduras because of concerns about human rights and corruption, therefore aid is being withheld to Honduras because of concerns about human rights and corruption. That’s that. Then she goes on NPR, unquestioningly repeats government claims, and she’s done her job. We would call this “propaganda” if it happened in the Soviet Union, but it’s called “journalism” when it happens here.

Honduras: Three Farmers Killed During Land Eviction

Agencia Púlsar | May 22, 2013

In the north of Honduras, in the community of San Manuel Cortés, three peasants were killed and two others wounded on Friday, when they tried to enter the lands that were expropriated last year by the Instituto Nacional Agrario (National Agrarian Institute). Valentín Caravantes, Celso Ruiz y Celedonio Avelar, who died at the scene, were members of the Farmers’ Movement of San Manuel Cortés (MOCSAM), located about 200kms from the capital.

The men entered the land because they obtained an order from the Court of Criminal Appeals, which stated that the evictions carried out in February 2012 against MOCSAM were illegal, reports the National Popular Resistance Front of Honduras (FNRP). “Security guards from the Honduran Sugar Company (CAHSA) fired at the three farmers,” FNRP added.

Brothers Aníbal and Adolfo Melgar were also seriously injured in the shooting and were immediately taken to a hospital in the municipality of San Pedro Sula.

For three years now MOCSAM has been demanding more than 3,000 acres of land which is currently possessed by the CAHSA company and exceeds 250 acres, the maximum a person or a firm can own in Valle de Sula under the country’s agrarian law.

The incident is the latest in a long series of clashes, which have ended up with many deaths over the past few years. In February, more than 1,000 peasants took back land after being expelled by British/South African beverages multinational SAB Miller in August 2012. And earlier this year, in March, the ongoing conflict between farmers and the Honduran government has resulted in the eviction of over 1,500 people from their land in the south of the country.

Related articles

- The New York Times on Venezuela and Honduras: A Case of Journalistic Misconduct

- Senator Menendez Meets with President Lobo to Discuss U.S. Funding for Honduras

- Honduras: Terror in the Aguán

- Will the World Bank Stop Investing in Campesino Assassinations?

- Killings Continue in Bajo Aguán as New Report Documents Abuses by U.S.-Trained Honduran Special Forces Unit

- Honduras: Murdered Lawyer’s Brother Killed in Aguán

- Step by Step: Honduras Walk for Dignity and Sovereignty

- World Bank Must End Support for Honduran Palm Oil Company Implicated in Murder

The New York Times on Venezuela and Honduras: A Case of Journalistic Misconduct

By Keane Bhatt | NACLA | May 8 2013

The day after Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez died, New York Times reporter Lizette Alvarez provided a sympathetic portrayal of “outpourings of raucous celebration and, to many, cautious optimism for the future” in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Her article, “Venezuelan Expatriates See a Reason to Celebrate,” noted that many had come to Miami to escape Chávez’s “iron grip on the nation,” and quoted a Venezuelan computer software consultant who said, bluntly: “We had a dictator. There were no laws, no justice.”1

A credulous reader of Alvarez’s report would have no idea that since 1998, Chávez had triumphed in 14 of 15 elections or referenda, all of which were deemed free and fair by international monitors. Chávez’s most recent reelection, won by an 11-point margin, boasted an 81% participation rate; former president Jimmy Carter described the “election process in Venezuela” as “the best in the world” out of 92 cases that the Carter Center had evaluated (an endorsement that, to date, has never been reported by the Times).2

In contrast to Alvarez, who allowed her quotation describing Chávez as a dictator to stand uncontested, Times reporter Neela Banerjee in 2008 cited false accusations hurled at President Obama by opponents—“he is a Muslim who attended a madrassa in Indonesia as a boy and was sworn into office on the Koran”—but immediately invalidated them: “In fact, he is a Christian who was sworn in on a Bible,” she wrote in her next sentence.3 At the Times, it seems, facts are deployed on a case-by-case basis.

The Times editorial board was even more dishonest in the wake of Chávez’s death: “The Bush administration badly damaged Washington’s reputation throughout Latin America when it unwisely blessed a failed 2002 military coup attempt against Mr. Chávez,” wrote the paper, concealing its editorial board’s own role in blessing that very coup at the time. In 2002, with the “resignation [sic] of President Hugo Chávez, Venezuelan democracy is no longer threatened by a would-be dictator,” declared a Times editorial, bizarrely adding that “Washington never publicly demonized Mr. Chávez,” that actual dictator Pedro Carmona was simply “a respected business leader,” and that the U.S.-backed, two-day coup was “a purely Venezuelan affair.”4

The editorial board—an initial champion of the de facto regime that issued a diktat within hours to dissolve practically every branch of government, including Venezuela’s National Assembly and Supreme Court—would 11 years later brazenly criticize Chávez after his death for having “dominated Venezuelan politics for 14 years with authoritarian methods.” The newspaper argued that Chávez’s government “weakened judicial independence, intimidated political opponents and human rights defenders, and ignored rampant, and often deadly, violence by the police and prison guards.” After lambasting Chávez’s record, the piece concluded that the United States “should now make clear its support for democratic and civilian transition in a post-Chávez Venezuela”—as if Chávez were anyone other than a fairly elected leader with an overwhelming popular mandate.

But there is a country currently in the grip of an undemocratic, illegitimate government that much more closely corresponds with the Times editorial board’s depiction of Venezuela: Honduras, which in 2009 suffered a coup d’état that deposed its freely elected, left-leaning president, Manuel Zelaya.

While the Times criticized Chávez for weakening judicial independence, the newspaper could not be bothered to even report on the extraordinary institutional breakdown of Honduras, when in December 2012, its Congress illegally sacked four Supreme Court justices who voted against a law proposed by the president, Porfirio Lobo, who himself had came to power in 2009 in repressive, sham elections held under a post-coup military dictatorship and boycotted by most international election observers.

When it comes to intimidation of political opponents and human rights defenders, Venezuela’s problems are almost imperceptible compared with those of Honduras. Over 14 years under Chávez, Venezuela has had no record of disappearances or murders of such individuals. In post-coup Honduras, the practice is now endemic. In one year alone—2012—at least four leaders of the Zelaya-organized opposition party Libre were slain, including mayoral candidate Edgardo Adalid Motiño. In addition, two dozen journalists and 70 members of the LGBT community have been killed since the coup, including prominent LGBT anti-coup activists like Walter Tróchez and Erick Martinez (neither case was sufficiently notable so as to warrant a mention in the Times).

And although the Times editors decried police violence in Venezuela, the Honduran police systematically engage in extrajudicial killings of their own citizens. In December 2012, Julieta Castellanos, the chancellor of Honduras’s largest university, presented the findings of a report detailing 149 killings committed by the Honduran National Police over the past two years under Porfirio Lobo. In the face of over six killings by the police a month, she warned, “It is alarming that the police themselves are the ones killing people in this country. The public is in a state of defenselessness…”5 Such alarm is further justified by Lobo’s appointment of Juan Carlos “El Tigre” Bonilla as director of the National Police, despite reports that he once oversaw death squads.6

Finally, the Times editorial board lamented Venezuelan prison violence. But consider for context that the NGO Venezuelan Prisons Observatory, consistently critical of Chávez, reported 591 prison deaths in 2012 for the country of 30 million.7 In Honduras, a country with slightly more than a quarter of Venezuela’s population, over 360 died in just one incident—a 2012 prison fire in Comayagua, in which prison authorities kept firefighters from handling the conflagration for 30 crucial minutes while the inmates’ doors remained locked. According to survivors, the guards ignored their pleas for help as many burned alive.8

Given the contrast in the two countries’ democratic credentials and human rights records, obvious questions arise: How has The New York Times portrayed Venezuela and Honduras since Honduras’s 2009 coup d’état? If, in both its news and opinion pages, the Times regularly prints accusations of Venezuelan authoritarianism, what terminology has the Times employed to describe the military government headed by Roberto Micheletti, which assumed power after Zelaya’s overthrow, or the illegitimate Lobo administration that succeeded it?

The answer is revealing. For almost four years, the Times has maintained a double standard that is literally unfailing. Not a single contributor in the Times’ over 100 news and opinion articles has ever referred to the Honduran government as “autocratic,” “undemocratic,” or “authoritarian.” Nor have Times writers ever once labeled Micheletti or Lobo “despots,” “tyrants,” “strongmen,” “dictators,” or “caudillos.”

At the same time, from June 28, 2009, to March 7, 2013, the newspaper has printed at least 15 news and opinion articles in which its contributors have used any number of the aforementioned epithets for Chávez.9 (This methodology excludes the typically vitriolic anti-Chávez blog entries that the paper features on its website, as well as print pieces like Lizette Alvarez’s, which quote someone describing Chávez as a dictator.)

At the same time, from June 28, 2009, to March 7, 2013, the newspaper has printed at least 15 news and opinion articles in which its contributors have used any number of the aforementioned epithets for Chávez.9 (This methodology excludes the typically vitriolic anti-Chávez blog entries that the paper features on its website, as well as print pieces like Lizette Alvarez’s, which quote someone describing Chávez as a dictator.)

During this period, the paper’s news reporters themselves have referred to Chávez as a “despot,” an “authoritarian ruler,” and an “autocrat”; its opinion writers have deemed him a “petro-dictator,” an “indomitable strongman,” a “brutal neo-authoritarian,” a “warmonger,” and a “colonel-turned-oil-sultan.” On the eve of Venezuela’s October elections, a Times op-ed managed to call the Chávez administration “authoritarian” no fewer than three times in 800 words.10 And Chávez’s death offered no reprieve from this tendency: On March 6, reporter Simon Romero wrote about Chávez’s gait—he “strutt[ed] like the strongman in a caudillo novel”—and concluded that Chávez had “become, indeed, a caudillo.”11

These most basic violations of journalistic standards—referring to a democratically elected leader as a ruler with absolute power—does not simply end with its writers. On July 24, 2011, Bill Keller, then the newspaper’s executive editor, wrote the piece, “Why Tyrants Love the Murdoch Scandal,” which included a graphic of Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe side by side with Chávez. Keller referred to them both when he concluded, “Autocrats will be autocrats.”12

But if despotism, defined as the cruel and oppressive exercise of absolute power, is to have any meaning, it must apply to the Honduran government, whose military—not just its police—routinely kills innocent civilians. On May 26, 2012, for example, Honduran special forces killed 15-year-old Ebed Yanez, and high-level officers allegedly managed its cover-up by dispatching “six to eight masked soldiers in dark uniforms” to the teenager’s body, poking it with rifles, and “[picking] up the empty bullet casings” to conceal evidence that could be linked back to the military, according to the Associated Press.13

The paradox of the Times—its derisive posture toward what it considers antidemocratic tendencies in Venezuela as it simultaneously avoids the same treatment of Honduras’s inarguable repression—can only be explained by one crucial factor: Honduras has been a firm U.S. ally since Zelaya’s overthrow.

Photo Credit: SOA Watch

In fact, the unit accused of killing Yanez was armed, trained, and vetted by the United States—even its trucks were donated by the U.S. government. As the AP further reported, in 2012, the U.S. Defense Department appropriated $67.4 million for Honduran military contracts, with an additional “$89 million in annual spending to maintain Joint Task Force Bravo, a 600-member U.S. unit based at Soto Cano Air Base.” Furthermore, “neither the State Department nor the Pentagon could provide details explaining a 2011 $1.3 billion authorization for exports of military electronics to Honduras.”14

The Times’ scrupulous, unerring record of avoiding disparaging characterizations of Honduras’s human-rights-violating government may explain why it has never once made reference to 94 Congress members’ demand that the Obama administration withhold U.S. assistance to the Honduran military and police in March 2012. Nor has the paper reported on 84 Congress members’ letter to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton later that year, condemning Honduras’s “institutional breakdown” and “judicial impunity.”15

When evaluating the newspaper’s relative silence on Honduras, it is worth imagining if Chávez were to have ascended to power in as dubious a manner as Lobo; if for years Venezuela’s government permitted its security apparatus to regularly kill civilians; or if the Chávez administration presided over conditions of impunity under which political opponents and human rights activists were disappeared, tortured, and killed.

As a careful examination of the language and coverage of nearly four years of New York Times articles reveals, concern for freedom and democracy in Latin America has not been an honest concern for the liberal media institution. The paper’s unwavering conformity to the posture of the U.S. State Department—consistently vilifying an official U.S. enemy while systematically downplaying the crimes of a U.S. ally—shows that its foremost priority is to subordinate itself to the priorities of Washington.

1. Lizette Alvarez, ““Venezuelan Expatriates See a Reason to Celebrate,” The New York Times, March 6, 2013.

2. Keane Bhatt, “A Hall of Shame for Venezuelan Elections Coverage,” Manufacturing Contempt (blog), nacla.org, October 8, 2012.

3. Neela Banerjee, “Obama Walks a Difficult Path as He Courts Jewish Voters,” The New York Times, March 1, 2008.

4. “Hugo Chávez Departs,” The New York Times, April 13, 2002.

5. “Policías de Honduras, Responsables de 149 Muertes Violentas,” La Prensa, December 3, 2012.

6. Katherine Corcoran and Martha Mendoza, “Juan Carlos Bonilla Valladares, Honduras Police Chief, Investigated In Killing,” Associated Press, June 1, 2012.

7. Fabiola Sánchez, “Venezuela Prison Deaths: 591 Detainees Killed Country’s Jails Last Year,” Associated Press, January 31, 2013.

8. “Hundreds Killed in ‘Hellish’ Fire at Prison in Honduras,” Associated Press, February 16, 2012.

9. Author’s research, using LexisNexis database searches for identical terms in reference to the two countries. For a detailed list of examples, contact him at keane.l.bhatt@gmail.com.

10. Francisco Toro, “How Hugo Chávez Became Irrelevant,” The New York Times, October 6, 2012.

11. Simon Romero, “Hugo Chávez, Leader Who Transformed Venezuela, Dies at 58,” The New York Times, March 6, 2013.

12. Bill Keller, “Why Tyrants Love the Murdoch Scandal,” The New York Times Magazine, July 24, 2011.

13. Alberto Arce, “Dad Seeks Justice for Slain Son in Broken Honduras,” Associated Press, November 12, 2012.

14. Martha Mendoza, “US Military Expands Its Drug War in Latin America,” Associated Press, February 3, 2013.

15. Office of Representative Jan Schakowsky, “94 House Members Send Letter to Secretary Clinton Calling for Suspension of Assistance to Honduras,” March 13, 2012. Correspondence from Jared Polis et al. to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, June 26, 2012.

Related articles

- U.S. Seeks to Get Rid of Left Governments in Latin America (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- The New Yorker Should Ignore Jon Lee Anderson and Issue a Correction on Venezuela (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- The New Yorker Corrects Two Errors on Venezuela, Refuses a Third (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- Nicolas Maduro did not Steal the Venezuelan Elections (venezuelanalysis.com)

- Honduras: Murdered Lawyer’s Brother Killed in Aguán (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- NPR Examines One Side of Honduran “Model Cities” Debate (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- IMF Ignores Proven Alternatives With Recommendations to Honduras (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- Killings Continue in Bajo Aguán as New Report Documents Abuses by U.S.-Trained Honduran Special Forces Unit (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- Honduras: Miguel Facusse is Tragically Misunderstood (alethonews.wordpress.com)

The New Yorker Should Ignore Jon Lee Anderson and Issue a Correction on Venezuela

By Keane Bhatt | NACLA | April 24, 2013

As a result of many dozens—possibly hundreds—of messages from readers over the past few weeks that criticized The New Yorker’s inaccurate coverage of Venezuela, reporter Jon Lee Anderson issued a response in an online post on April 23. This marks the first time the magazine has publicly addressed its controversial and erroneous labeling of Venezuela as one of the world’s most “socially unequal” countries (I highlighted the error in mid-March). Although Anderson deprives his readers of the opportunity to evaluate his critics’ arguments (he offered no hyperlinks to either of my two articles on the subject, nor to posts by Corey Robin, Jim Naureckas, and others), he is clearly writing in response to those assertions.

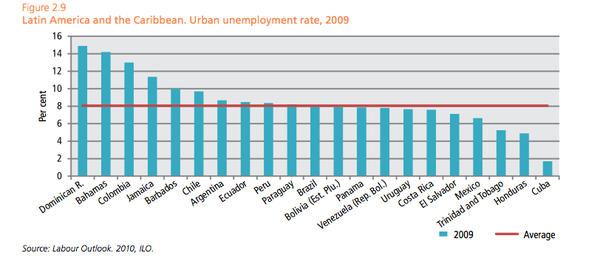

To his credit, Anderson unequivocally admits two of his three errors: regarding Venezuela’s homicides, he acknowledges that he falsely wrote “that Venezuela had the highest homicide rate in Latin America. Actually, Honduras has the top rate.” Anderson proceeds to explain why Venezuela’s high homicide rate is nevertheless a grave problem—a position none of his critics, myself included, dispute.

The importance of this error rests instead in its revelation of a media culture under the influence of the consistent demonization of a country deemed an official U.S. enemy. This culture certainly played a role in allowing Anderson’s obvious falsehood to remain uncorrected for five months—five months after I first wrote about it, one month after I directly and publicly confronted Anderson about the error, and even then, days after I wrote another article urging readers to demand a correction.

While The New Yorker has dedicated literally no articles to U.S. ally Honduras since its current leader Porfirio Lobo came to power in repressive, sham elections held under a military dictatorship, Anderson was allowed to assert that Venezuela—a country with half the per capita homicides of Honduras—was Latin America’s leader in murders. One might reasonably suspect that a claim on The New Yorker’s website asserting that the United States had a higher homicide rate than Bolivia (Bolivia’s rate is actually over two times as high), would be retracted more expeditiously.

Anderson’s explanation for his second error—claiming that Chávez came to office through a coup d’etat rather than a free and fair election—further lays bare the corrupting effects of the generalized vilification of Chávez on basic journalistic standards of accuracy.

Anderson writes that despite his gaffe, he obviously knew Chávez “gained the Presidency by winning an election in 1998,” as he had “interviewed Chávez a number of times, travelled with him, and came to know him fairly well.” For Anderson to write such an egregious misstatement, then, and have it pass through what is likely the most rigorous fact-checking process in the industry, exposes a pervasive ideology under which he and his many editors and fact-checkers operate. As Jim Naureckas of Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting wrote, “It’s like writing a long profile on Gerald Ford that refers to that time when he was elected president.”

Finally, Anderson offers a desperate attempt to justify his third factual error, stating:

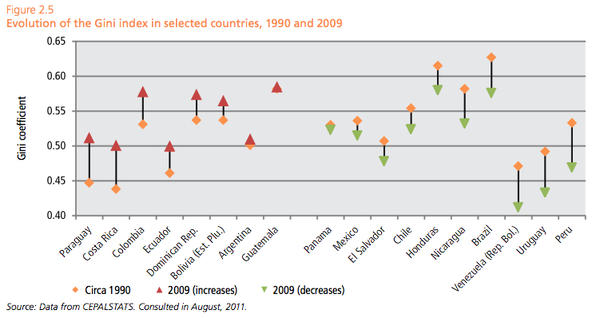

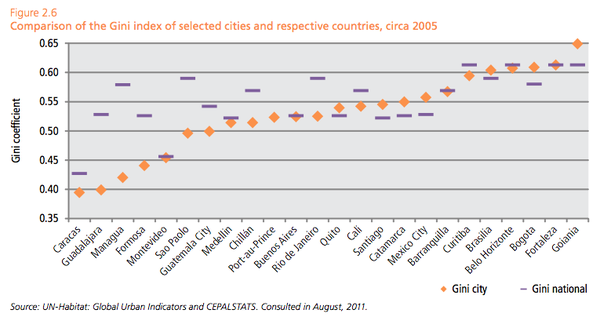

A number of letters I’ve received dispute, out of context, my reference to “the same Venezuela as ever: one of the world’s most oil-rich but socially unequal countries”; several cite an economic statistic known as the Gini coefficient—a measure of income inequality.

Notice that Anderson never tells his readers what Venezuela’s Gini coefficient actually is. According to the United Nations, Venezuela’s Gini, at 0.397, makes it the least unequal country in Latin America and squarely in the middle range of the rest of the world. Only by sidestepping this brutal empirical obstacle can Anderson attempt to lay out his case. He carries on by reposting three paragraphs of his original essay, which in no way mitigate the falsity of his original claim, for “context.” Anderson finally concludes by offering a novel justification for his error:

In terms of some of the components of social inequality, notably income and education, Chávez had some real achievements. (Income is what’s captured by the Gini coefficient, although that statistic has its own limitations, some particular to Venezuela.) But in housing and violence, his record was woefully insufficient. Those social factors are intimately related, to each other and to the question of equality.

A quick recap is in order before unpacking Anderson’s argument. Readers may remember that he first responded to evidence on income inequality by proclaiming, on Twitter, his agnosticism toward empirical data. Next, a senior editor at the magazine justified Anderson’s contention by arguing that Venezuela was one of the most unequal amongst other oil-rich countries—a point I debunked. Now, Anderson has settled on a definition of social inequality that minimizes Venezuela’s high educational and income equality in favor of high homicide rates and unequal housing.

But simply saying that Chávez’s record “was woefully insufficient” on housing and violence does not naturally equate to Venezuela’s standing as a world leader in social inequality. Anderson must rely on comparative international statistics to justify his position, but fails to do so.

While Venezuela’s homicide rate is high by international standards and a significant social ill, this alone does not necessarily make the country more socially unequal than another country with a lower homicide rate. Are Venezuelan homicides more skewed toward low-income residents than those in Costa Rica? Or Haiti? Are Venezuelan murders more targeted at women or ethnic minorities than those in Mexico or Guatemala? And given that the high homicide rate directly affects far fewer than one in a thousand Venezuelans annually, how could this statistic possibly outweigh the effect of massive income-inequality and poverty reductions? If he is solely basing his argument on murder rates, Anderson has no credible explanation as to why Venezuela is one of the world’s most socially unequal countries.

Anderson also doesn’t offer statistics showing that housing is more unequal in Venezuela than anywhere else. That’s because it’s not.

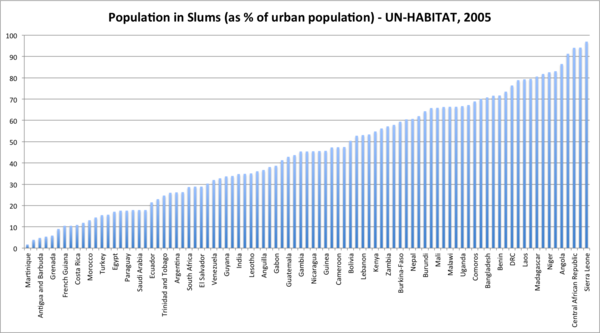

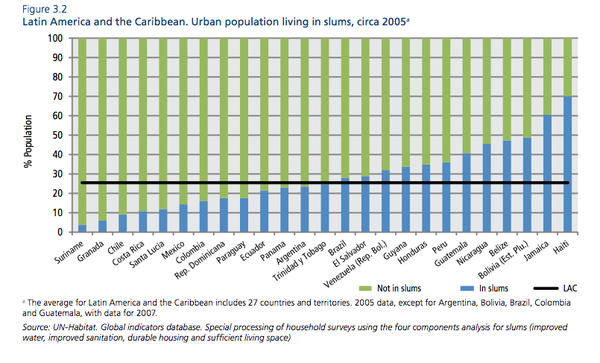

Out of the 91 countries for which the United Nations has available data, Venezuela is 61st in terms of the percentage of its urban population living in slums. That is to say, two-thirds of the world’s countries with available data have larger percentages of their urban citizens living as slum dwellers. In the Western Hemisphere, this includes Guayana, Honduras, Peru, Anguilla, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Belize, Bolivia, Jamaica, and Haiti.

It is also worth mentioning that this data was taken from 2005, when the percentage of Venezuela’s urban population living in poverty and extreme poverty was at 37%. By 2010, according to the United Nations, it had been cut by a quarter, to 28% (p. 43). Furthermore, 2005 predates a massive governmental push in 2011 to build affordable housing. Earlier this year, Venezuela’s Housing Commission chair asserted that “in the years 2011 and 2012, the Bolivarian government together with the people reached the goal of building 350,000 homes.”

It appears, then, that Anderson has discovered a new definition of “social inequality” that has eluded economists and sociologists worldwide—one that systematically downplays Venezuela’s educational and income equality while emphasizing a high frequency of murders and a rate of slum-dwelling that is low by international standards.

While one can applaud Jon Lee Anderson for finally acknowledging the value of social indicators and statistical data, he and his magazine cannot be allowed to define “social inequality” any way they see fit. No social scientist analyzing the available data could argue, like Anderson, that Venezuela is one of the world’s most socially unequal countries. While semantics games may be expedient in avoiding a necessary correction, readers should let The New Yorker’s editor David Remnick (david_remnick@newyorker.com) know that a retraction of Anderson’s claim is long overdue.

Update (4/24): FAIR’s Jim Naureckas also offers sharp criticism of Jon Lee Anderson and his fact-checkers for a transparently inadequate attempt to justify his error regarding Venezuela’s social inequality. Read more, at “Jon Lee Anderson Explains: Because I Said So.”

~

Keane Bhatt is an activist in Washington, D.C. He has worked in the United States and Latin America on a variety of campaigns related to community development and social justice. His analyses and opinions have appeared in a range of outlets, including NPR, The Nation, The St. Petersburg Times, and CNN En Español. He is the author of the NACLA blog “Manufacturing Contempt,” which critically analyzes the U.S. press and its portrayal of the hemisphere. Connect with his blog on Twitter: @KeaneBhatt

Related articles

- The New Yorker Corrects Two Errors on Venezuela, Refuses a Third (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- On Venezuela, The New Yorker’s Jon Lee Anderson Fails at Arithmetic (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- 50 Truths about Hugo Chavez and the Bolivarian Revolution (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- ‘Little Twerp … Get a Life’: The New Yorker’s Jon Lee Anderson Thinks He’s Somebody on Twitter (gawker.com)

Honduras: Terror in the Aguán

By Greg McCain | Upside Down World | April 11, 2013

During the first week of April, the Honduran daily newspaper La Prensa ran a series of articles that included photos, a video and a link to a montage of past articles entitled Terror en el Bajo Aguán. The major thrust of the series is that there are heavily armed clandestine groups of men training in the region. The photos and video show them with AK47s, M16s, and .223 assault rifles, all of which are military issue. All of the men are wearing ski masks over their faces and they appear to be playing to the camera, running in defensive stances, crawling on the ground and being sure to showoff their heavy firepower, all at the direction of whoever is holding the camera. An April 1 article states that there have been more than 90 deaths in the Aguán attributed to people with high caliber arms like the ones shown in the photos. It states that the latest one was a campesino, but it fails to point out that these more than 90 deaths since the coup in 2009 were all campesinos who have been murdered by sicarios: assassins who mainly perform drive by shootings.

Not unexpectedly, the new propaganda campaign being orchestrated by Colonel German Alfaro, commander of Operation Xatruch III and graduate of the School of the Americas, has been carried out with the help of the pro-ruling elite, pro-coup mainstream media. In a further attempt to criminalize the campesino movements, the La Prensa series, by implication and by direct assertions, links the struggles of the campesinos to acquire land that is rightfully and legally theirs to these mysterious armed groups that are roving the Aguán and allegedly terrorizing the private security forces of the rich landowners.

The video of the alleged training maneuvers would be laughable in its obvious staging if the repression that has befallen the campesinos at the hands of the private security guards, the Honduran military, and the National police wasn’t so tragic and ever present. These forces are not just working side-by-side, but are also interchangeable since the security companies that Dinant contracts often hire police and military personnel.

Colonel Alfaro states several times to La Prensa that the identities of these clandestine groups are known and that they even know who the leaders are. In a March 1, 2013 La Prensa article, he asserts that they are being trained by Nicaraguans’ with combat training. He declares that these groups go into the fincas owned by the rich landowners, such as Miguel Facussé’s Paso Aguán, “to terrorize and scare off the security guards. Later, the campesinos go into the plantations to steal the fruit and then money is exchanged at some later date.” No explanation is given as to why it is that campesinos are being killed in overwhelming numbers if this symbiotic relationship truly exists.

The La Prensa “exposé” raises more questions than it answers. If it is the security guards who are being terrorized then why aren’t there huge numbers of their deaths? Furthermore, why are they only a tiny fraction of the campesino deaths, and often found to be the result of infighting among the guards? Why are the campesinos from MARCA who have successfully fought in the courts to retain possession of their land being assassinated? Their lawyer, Antonio Trejo, was assassinated last November in Tegucigalpa after successfully winning the case that secured the land for three of MARCA’s collectives. His brother was later assassinated in Tocoa while investigating his murder. While denying any responsibility, Facussé told an L.A. Times reporter in a December 21, 2012 interview that he certainly had reason to see the lawyer dead. The National Police have attempted to raise spurious claims that the Trejo’s were involved with different less than desirable elements, creating red herrings to take the focus off of Facussé.

There are further questions raised by Alfaro’s claims of there being a connection between armed groups and campesinos. Why are the leaders of MUCA being stopped at every police checkpoint as they drive from Tocoa on their way to a meeting in Siguatepeque in the south. At one checkpoint an officer said to another, “It’s them… they are here.” Later, when they decide that it is safer not to drive any further, they stop at a hotel to rest and then take a bus at 3am to their destination. A group of armed men was seen by the campesino’s driver, who stayed behind, pulling up to the hotel at 3:30 a.m. and question the receptionist about them. Further, why are Facusse’s guards and police and military on a regular basis harassing the MUCA collectives. A truck full of soldiers drove through the community of La Confiansa on the eve of the internal elections shouting out “we’re hunting for Tacamiches” a derogatory term used by the upper classes and police and military to denote campesinos? Why have the military been surrounding the campesino community of La Panama, which borders the Paso Aguán finca, and in which two bodies of members of the community have been dug up near where the private security guards camped? Meanwhile, more are suspected buried there, but why won’t the police and private security, and indeed, the military allow the community to search for the bodies of those missing?

These are questions that neither the mainstream media will ask, nor will Colonel Alfaro answer. Instead they work in concert to manufacture a connection between alleged criminal groups and the campesinos. Alfaro’s motives are made clear when he states that they are there to protect the property and the palm fruit of the rich landowners. Soldiers are often seen riding in or along side Facusse’s Dinant trucks and they along with the National Police intermingle on a regular basis with Facussé’s and the other rich landowner’s guards, who have often been described by those living in the Aguán as paramilitaries.

Alfaro claims that, after the National Congress passed a decree in 2012 that banned all firearms from being possessed except by the police, military and private security, they captured 200 weapons in the first month (he does not specify if they were of high caliber like AK47s or if they were .22 rifles or handguns), and then an average of about 14 per month since then. It is evident from his boast that the military has greatly disarmed the general public, while it is evident just by driving up and down the roads between Tocoa and Trujillo that the arms of gruesome caliber, as the newspaper describes them, are in the hands of the police, military and paramilitary of Facussé and the other rich landlords.

There are both police and military checkpoints that randomly stop cars and buses along the main road between these two cities. When a bus is stopped all the men are told to leave and keep their bags and backpacks on board along with the women. The men are then told to press up against the bus with arms and legs spread while the very young soldiers of the 15th Battalion, with their rifles strapped across their chests, do a body pat down while looking at IDs. Other soldiers search the personal belongings on the bus. Off to the side of the road is a military personnel carrier that has a mounted machine gun pointed toward the street. Alfaro doesn’t explain if this is the method that has led to the discovery and confiscation of so many weapons, but it has been successful in labeling every citizen as a potential criminal and preparing the streets for Martial Law as the country prepares for the general elections in November.

In late February, several hundred police, military, and security guards surrounded the community of La Panama, as they have done various subsequent times since then. They proceeded to knock down a security gate that had been erected to keep the paramilitary guards from invading the community. In July of 2012, La Panama found it necessary to put up the gate after one of the community’s leaders, Gregorio Chavez, was disappeared and his corpse later found in the Paso Aguán. His shallow grave was a ten-minute walk from where Facussé’s paramilitary guards had set up an encampment. The community, after pleading with police to accompany them onto the finca, and after international human rights observers had visited and taken testimonies from the community, finally were allowed access. As Señor Chavez’ son and brother pulled the cadaver from the ground it was apparent from marks on the body that he had been tortured. Previous to Chavez’ murder the guards had been harassing him, shooting his chickens, and threatening to do the same to him and his family. They often drove up and down the road that goes through the community with their guns pointing out at the children who played in the yards.

Dinant had put up a building in the middle of the community that functioned as both a guardhouse and a parking space for their palm fruit trucks. A week before his disappearance Gregorio Chavez had gone to this building to complain to someone in charge about the threats and the killing of his chickens. It was also in this building that many in the community had seen the bicycle of one of the disappeared after he went missing. It is suspected that he is buried in the Paso Aguán. It could be the remains that were recently found on April 3. A security guard who had connections to the community tipped them off as to where they could find the body. The community is hoping, with the help of COFADEH and other human rights groups, to get an international forensic team to positively identify who it is.

This latest news was revealed at a press conference in Tegucigalpa held on the April 3 by the Agrarian Platform of the Campesinos of the Aguán (PARCA, in its Spanish acronym). PARCA is a new initiative formed by 13 campesino movements to better support each other as they face ever-increasing threats to their rights to the land. The press conference was called in response to the La Prensa stories. Yoni Rivas, Secretary General of MUCA, reasserted that the campesinos have no connection to any armed groups. In fact, it was the campesinos who had gone to the press in 2011 to point out that there were armed thugs killing campesinos in the Aguán and he showed pictures of armed men with automatic weapons wearing uniforms that matched the clothes worn by Dinant’s security forces.

The ultimate question is, if Colonel Alfaro and Operation Xatruch are simply doing what they say they are, “maintaining the peace and harmony of the people of Colon,” then why is he conducting press conferences denouncing both Honduran and international human rights groups? On February 18, 2013, in a clear act of aggression toward these groups and in a further attempt at criminalization of the campesinos, he called out human rights observers and campesino leaders. He published the phone numbers of international human rights observers in the US and Europe, and attempted to set up a confrontation between what he refers to as the “Laboriosa población,” the hard working people of the department of Colon against the aforementioned campesino groups referring to them as “a minority”, who create permanent friction and a constant problem of disrespect for the legally established laws and legal authorities. Alfaro’s and the Honduran military’s disdain for the campesinos is further illustrated in the report, Human Rights Violations Attributed to Military Forces in the Bajo Aguan Valley in Honduras written by Annie Bird of Rights Action where she states that her report, “describe[es] the abuses, many of them grave human rights violations, in which soldiers from the 15th Battalion were present and/ or direct participants [in the killings of campesinos]; in either case the 15th Battalion is a responsible party to the violations.” The 15th Battalion is where Xatruch III and Colonel Alfaro are stationed.

In a further indictment of Alfaro’s disingenuousness, during Xatruch’s raid of La Panama in February, there was, coincidentally, a human rights delegation from the US-El Salvador Sister Cities organization visiting the community. This forced the military, police and security guards to retreat. Much of the military force moved into the Paso Aguán finca. Later, members of the community who didn’t want their names made public stated that Alfaro attempted to “negotiate” with the community, but told them to stop talking to human rights groups. They of course denied his request. Today, the tensions between the community and the heavily armed forces continue as the military remain in the finca protecting Facussé’s palm fruit.

Related articles

- Will the World Bank Stop Investing in Campesino Assassinations? (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- Killings Continue in Bajo Aguán as New Report Documents Abuses by U.S.-Trained Honduran Special Forces Unit (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- Honduras: Murdered Lawyer’s Brother Killed in Aguán (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- Step by Step: Honduras Walk for Dignity and Sovereignty (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- World Bank Must End Support for Honduran Palm Oil Company Implicated in Murder (alethonews.wordpress.com)

Official Honduran Report on May 11 Shooting Incident is a New Injustice to Victims

By Dan Beeton | CEPR Americas Blog | April 11, 2013

CEPR has released a new paper, along with the human rights organization Rights Action, examining the Honduran Public Ministry’s official report on the May 11, 2012 shooting incident last year in which four local villagers were killed in Ahuas in Honduras’ Moskitia region during a counternarcotics operation involving U.S. and Honduran agents. This is also the first time that the Public Ministry’s report has been made available to the public, posted to Scribd in English here, and Spanish here.

The Honduran Public Ministry’s report deserves special scrutiny because thus far it represents the official version of events according to the Honduran authorities. And since the U.S. government has declined to conduct its own investigation – despite the wishes of 58 members of Congress – it also represents by default the version of events tacitly endorsed by U.S. authorities as well. The DEA and State Department didn’t allow Honduran investigators to question the U.S. agents and contractors that participated in the May 11 operation. At the same time a U.S. police detective working for the U.S. Embassy reportedly participated in the Public Ministry’s investigation, so the U.S. also bears some responsibility for the report’s flaws.

The CEPR/Rights Action paper found that the Public Ministry’s report:

- Makes “observations” (not conclusions) that are not supported by the evidence cited;

- Omits key testimony, that would implicate the DEA, from police who were involved in the May 11 incident;

- Relies on incomplete forensic examinations of the weapons involved, improper forensic examinations of the victims’ bodies and other improperly gathered evidence;

- Does not attempt to establish who is ultimately responsible for the killings;

- Ignores eyewitness reports claiming that at least one State Department-titled helicopter fired on the passenger boat carrying the shooting victims;

- Does not attempt to establish whether the victims were “in any way involved in drug trafficking” as both Honduran and U.S. officials originally alleged;

- Does not attempt to establish what authority was actually in charge of the operation;

- Appears to be focused on absolving the DEA of all responsibility in the killings.

The CEPR/Rights Action report represents the first such public critique of the Public Ministry’s report. As we have previously noted, there are significant discrepancies between different accounts of the May 11 events, including those of Honduran police officers who participated in (and say the DEA was in charge of) the operation. These discrepancies – cited in a separate report published by the Honduras National Commission of Human Rights (CONADEH) – are not mentioned in the Public Ministry report. Nor does the report include police testimony indicating that a DEA agent ordered one of the State Department helicopters to open fire on the passenger boat in which four people were killed.

The report concludes by calling for the U.S. government to carry out its own investigation of the Ahuas incident to better determine what occurred and to determine what responsibility, if any, DEA agents had in the killings. It also calls on the U.S. government to cease being an obstacle to an already flawed investigation by making the relevant DEA agents, weapons and documents – including an aerial surveillance video of the Ahuas operation in its entirety – available to investigators.

The new CEPR/Rights Action paper follows the “Collateral Damage of a Drug War” report released last year which was based on eyewitness testimony and other evidence the authors obtained in Honduras and concluded that the DEA played a central role in the shooting incident.

Related article

- Obama Administration Refuses to Investigate Alleged DEA Killing of Women and Child in Honduras (alethonews.wordpress.com)

“We’re Witnessing a Reactivation of the Death Squads of the ‘80s”

An Interview with Bertha Oliva of COFADEH

By Alex Main | cepr Americas Blog | March 29, 2013

Bertha Oliva is the General Coordinator of COFADEH, the Committee of Relatives of the Disappeared and Detained in Honduras. Bertha’s husband was “disappeared” in 1981, a period when death squads were active in Honduras. She founded COFADEH together with other women who lost their loved ones, in order to seek justice and compensation for the families of the hundreds of dissidents that were “disappeared” between 1979 and 1989. Since then Bertha and COFADEH have taken on some of the country’s most emblematic human rights cases and were a strong voice in opposition to the 2009 coup d’Etat and the repression that followed. We interviewed her in Washington, D.C. on March 15th, shortly after she participated in a hearing on the human rights situation in Honduras at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). During the hearing she said that death squads are targeting social leaders, lawyers, journalists and other groups and called on the IACHR to visit Honduras in the next six months to take stock of the human rights situation ahead of the November general elections (Bertha’s testimony can be viewed here, beginning at 17:40).

Q: On various occasions you’ve said that what you’re seeing today in Honduras is reminiscent of the difficult times you experienced in the ‘80s and I’d like you to elaborate on that.

In the ‘80s we had armed forces that were excessively empowered. Today Honduras is extremely similar, with military officers exercising control over many of the country’s institutions. The military is now in the streets playing a security role – often substituting for the work of the police forces of the country.

In the ‘80s we also witnessed the practice of forced disappearances and assassinations. In that era it was clear that they were killing social leaders, political opponents, but they also assassinated people who had no ties to dissident groups in order to generate confusion in public opinion and try to disqualify our denunciations of the killings of family members who were political opponents.

Today they assassinate young people in a more atrocious fashion than in the ‘80s and we’re seeing a marked pattern of assassinations of women and youth. And within this mass of people that are assassinated there are political opponents. We refuse to dismiss these assassinations as simply a result of the extreme violence that we’re experiencing, as they try to tell the country. We say that it is a product of impunity and Honduras’ historical debt for failing to resolve cases perpetrated by state agents…

In the ‘80s the presence of the U.S. in the country was extremely significant. Today it’s the same. New bases have opened as a result of an anti-drug cooperation agreement signed between Honduras and the U.S.

In the ‘80s it was clear that political opponents were being eliminated. Today they’re also eliminating those who claim land rights, as exemplified in the Bajo Aguán. More than 98 land rights activists have been assassinated. The campesino sector in the Bajo Aguán has been psychologically and emotionally tortured on top of the physical torture that certain campesino leaders have been subjected to.

Q: Today in the hearing on human rights in Honduras at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights you discussed death squads. Death squads were active in the ‘80s and now you believe that this sinister phenomenon is coming back.

It’s certain that death squads are a product of the impunity that we’ve seen in Honduras. The death squads of the past were never really dismantled. What we’re witnessing is a reactivation of these death squads. And we’re seeing it quite clearly. We’ve seen videos of incidents in the street where masked men with military training and unmarked vehicles assassinate young people. There is the recent case of the journalist Julio Ernesto Alvarado who gave up his news program from 10pm to midnight on Radio Globo because members of a death squad came to kill him, and to save his own life he had to stop doing his program.

In Honduras we had a military coup d’Etat and this resulted in persecution, an implosion of the state’s institutions which has left us with a dysfunctional judicial system and this has provided cover to those who wish to break the law.

And, what’s worse, state agents seem to have no political interest in improving and changing the situation. What we’re witnessing is a growing professionalization of the capacity to justify illegal acts: authorities’ assertion that they intend to investigate these acts, when that’s simply not true. In reality it seems the intention is to continue terrorizing the Honduran people, to make them submissive so as to undermine citizen action.

What we’d like to see in Honduras is real action to try to prevent crime rather than continued justification of the lack of progress of investigations into crimes.

Q: COFADEH is providing legal counsel to the victims and the families of the victims of the emblematic case that took place in May of last year in Ahuas, in which there was a police operation that involved U.S. agents and Honduran security agents that killed four people and injured a few others. Can you discuss the status of that case, over ten months after the killings took place?

Yes, we are the legal representatives of the victims in this case and, on the one hand, we are filing a complaint with Honduras’ judicial authorities to show or verify the responsibility of Honduran agents and DEA agents that participated in this incident.

But we’re also trying to reach out to the general public so that the case is better known and debated as this is the only real recourse we human rights defenders have: publicly denouncing the incident to see whether this will allow for some protection of the victims and of ourselves. But legally we see this as a very difficult case to move forward and this is where we can see that the authorities aren’t interested in investigating, let alone sanctioning, those responsible. The crime of the tragic attack against this indigenous community has been compounded by the crime of violating due process in the investigation.

We the legal representatives of the victims should have access to the case file. The Public Ministry [equivalent to the Attorney General’s Office in the U.S. – ed.] shouldn’t allow any obstacle to come in the way of our access to the file. They can’t legally prevent us from learning about the actions that have been taken in the course of the investigation because we are part of the defense. It is prohibited for either of the parties to be denied access to the case file. The file can be classified with regard to the general public, but not with regard to the parties representing the victims and the accused.

We haven’t seen all the files in this case. They haven’t been inserted in a binder [as is normally the case] in order to allow them to remove information when we ask for the file. How can we participate effectively in a trial when we can’t see all of the case file?

Q: And what evidence do you have of their having removed parts of the case file before sharing it with you?

One is that when we’ve been shown the case file it basically only contains documents that we’ve produced. We know the Public Ministry has carried out its own investigations; it has carried out the exhumation and autopsies of the deceased victims’ bodies for instance. As a side note, we weren’t informed that they were carrying out the exhumations of the victims. We’re left with the impression that the intention isn’t to find evidence but rather to remove [borrar] evidence… Our Public Ministry should be called a “Public Laundromat” because they’re engaged in destroying evidence.

Q: So you didn’t see the reports on the exhumations and autopsies of the victims in the Ahuas case file?

We haven’t seen them, just as we didn’t see the report that was sent by [Honduran Attorney General equivalent] Luís Alberto Rubi to the State Department of the United States. This indicates to us that they remove information and documentation from the case file that they don’t want us to see.

The Public Prosecutor [Attorney General equivalent] sent a report to a representative of the State Department, Maria Otero, with – for instance – the names of the Honduran police agents and military personnel that participated in the operation, though not the names of the DEA agents, with the apparent goal of barring them from any sort of responsibility.

Q: But you did end up managing to see the Public Ministry report sent to the State Department?

Yes, but not through the Public Ministry, but thanks to people outside Honduras who managed to get hold of a copy.

Q: In this report there is information based on testimony provided to the Public Ministry by police agents that participated in the Ahuas operation. Have you been able to see any of this original testimony?

No, we haven’t seen any of the testimony of the police agents.

Q: What is the current situation of the surviving victims of the Ahuas incident, and of the families of the victims?

The situation of the families, of the survivors, of the community is really very critical. They are emotionally and psychologically affected. Being on the receiving end of an armed aerial attack is a shock for a remote community that never expected an attack of this nature. Some of the community members were woken up by armed agents, were physically attacked and had certain belongings stolen.

I think that those that survived are no longer directly threatened but not all of them have recovered their physical abilities. For instance, a young man sustained a serious injury to his hand requiring an operation that cost 100,000 lempiras [over $5,000 – ed.]. Where can this boy, who doesn’t have anything, find this kind of money?

COFADEH ended up having to take care of him and he’s still in treatment in Tegucigalpa, far from his community. We are paying for his treatment and lodging him, feeding him and paying for his studies. This is the responsibility of the state and it has refused to assume this responsibility even though we requested urgent protective measures from the state. The state is good at providing technically well-designed reports before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, but it has been incapable of dealing with the needs of the survivors of this attack.

This sort of thing is a clear demonstration of their lack of interest in resolving and combatting the insecurity we’re experiencing, the political violence and the high level of impunity.

Q: What about the other injured victims?

We’ve had to bring them to Tegucigalpa to be treated. In the case of one boy they left studs [clavos] jutting out of his arm. He almost lost his arm because after the operation they sent him back to his community but with no medicine.

We’ve also had to provide care for other relatives of the survivors and the deceased victims. It’s impressive the level of neglect of these victims on the part of the state.

We [the human rights defenders] return to our country with the fear that the attacks will extend to us as a result of our decision to come and denounce a state that has shown itself incapable of assuming its responsibility.

Q: COFADEH has received threats and recently its offices were raided. Can you talk to me about your situation, your vulnerability, and what people in the U.S. can do to help?

Our situation isn’t good at all. I confess that we’re frightened because we love life, that’s why we dedicate ourselves to defending the lives of others. And I don’t want to die or be tortured. And I don’t want to have to confront state agents. But despite their machinery of hate and actions against us, they should know that they can’t stop us.

Fortunately we can count on support from people in the U.S. and the rest of the world, and I can reaffirm today that this support and this commitment of people abroad inspires us and makes us feel less alone. Because the worst that can happen for a human rights defender facing threats is to feel alone. That’s why we call on you to continue supporting us to defend the life and liberty of the citizens that need our help.

Related articles

- World Bank Must End Support for Honduran Palm Oil Company Implicated in Murder (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- Will Congress act to stop US support for Honduras’ death squad regime? | Mark Weisbrot (guardian.co.uk)