Data from Bolivia’s Election Add More Evidence That OAS Fabricated Last Year’s Fraud Claims

The MAS Received More Votes in Almost All of the OAS’s 86 Suspect Precincts in 2020 than in 2019

By Jake Johnston | CEPR | October 21, 2020

On Sunday, October 20, Bolivians went to the polls and overwhelmingly elected Luis Arce of the MAS party president. Private quick counts released the night of the vote showed Arce receiving more than 50 percent of the vote and holding a more than 20 percentage point lead over second place candidate Carlos Mesa. As of Wednesday morning, just over 88 percent of votes had been tallied in the official results system — and Arce’s lead is even greater. The MAS candidate’s vote share is, at the time of writing, 54.5 compared to 29.3 for Mesa. As the final votes are counted, Arce’s vote share will likely increase further.

At this point, there can be no questioning Arce’s victory. The election came nearly exactly a year after the October 2019 elections which were followed by violent protests and the ouster of then president Evo Morales, who resigned under pressure from the military. Official results in that vote showed Morales and the MAS party winning with a 10.56 percentage point advantage over Mesa, just over the 10 point margin of victory needed for Morales to win the election outright, without having to stand in a run-off election. However, the Organization of American States (OAS) alleged widespread manipulation of the results, feeding a narrative of electoral fraud that served as a pretext for the November 10, 2019 coup.

With Arce’s 2020 victory now all but confirmed, what do the 2020 results tell us about the OAS allegations of fraud in last year’s vote?

The OAS’s initial claims of fraud centered around a “drastic” and “inexplicable” change in the trend of the vote, which allegedly took place after the preliminary results system, or TREP, was suspended for nearly 24 hours. In the time since, myriad statistical analyses — from CEPR (beginning the day after the OAS allegations), and from academics at MIT, Tulane, University of Pennsylvania and elsewhere, have shown the OAS’s statistical analysis to be deeply flawed. In fact, there was no “inexplicable” change in the trend of the vote.

The OAS has refused to respond to these studies, or to queries about their statistical analysis from members of Congress, and has instead pointed to other alleged irregularities identified in the OAS audit. Statistical analysis is just informative, the OAS claimed, but the real evidence was in an audit that they carried out after the elections.

In that audit, the only evidence purporting to show an actual impact on the results of the elections were 226 tally sheets from 86 voting centers across the country. The OAS alleged that the tally sheets had been doctored. They noted that, if you removed the votes for Morales from all of these 226 tally sheets, his entire advantage above the 10 percentage point threshold for a first-round win disappeared. In other words, these 226 tally sheets served as supposed proof that Morales had cheated in order to win in the first round.

Excerpts from the OAS audit report

In March 2020, CEPR published an 82-page report detailing how the rest of the OAS allegations were just as flawed as the statistical analysis that formed the basis for the fraud narrative that led to Morales’s forced removal from office. We looked into these 226 tally sheets, showing the flaws in the OAS analysis and pointing out that the results in these voting centers closely matched results from previous elections. There was, in fact, nothing surprising about MAS performing extremely well in these areas. Further, we noted that while OAS officials had repeatedly spoken publicly about forged tally sheets, the auditors had provided no evidence to back up that allegation.

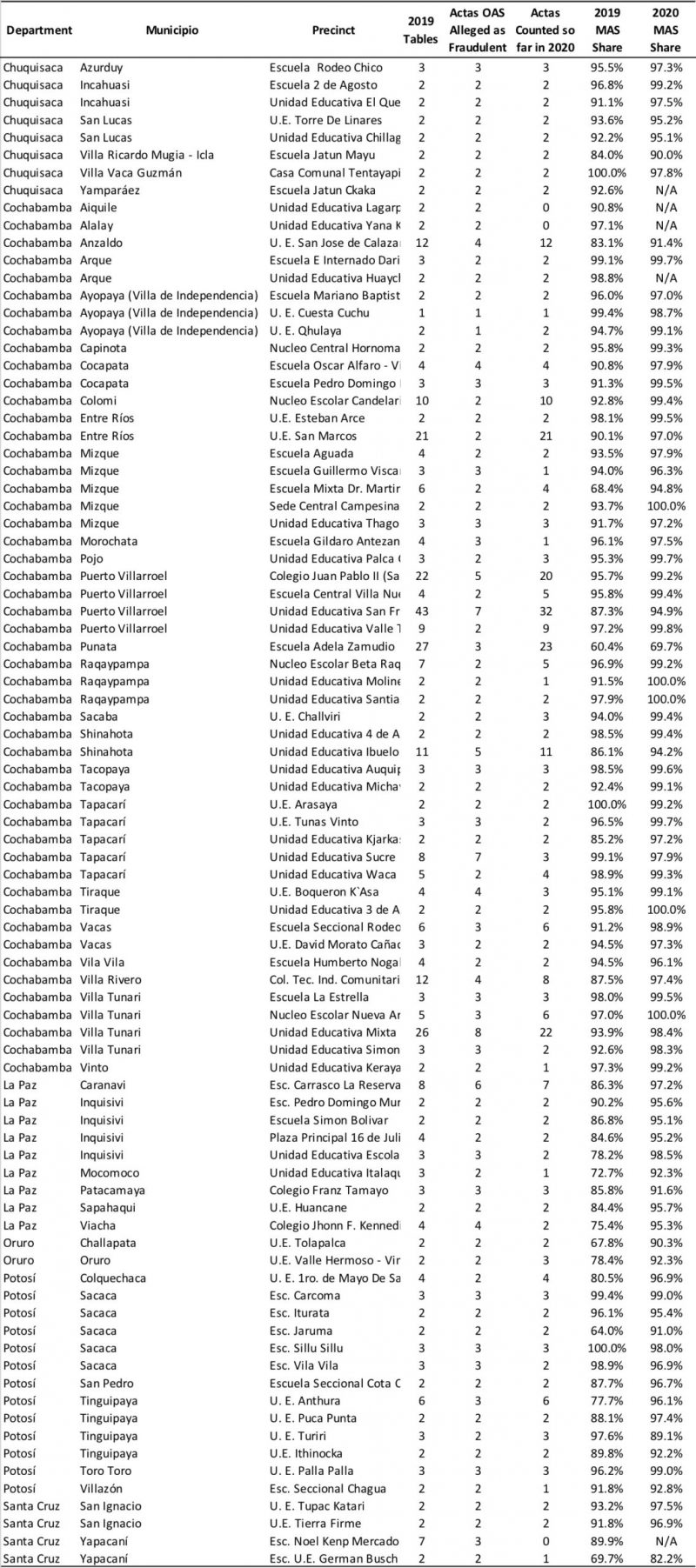

Now that there are disaggregated voting results from this Sunday’s elections, we can see that results in the centers where the OAS had allegedly identified doctored tally sheets follow the same patterns as in the 2019 elections. Table 1, below, presents the 2020 results (with 88 percent of votes counted overall) in all 86 voting centers where the OAS alleged that tally sheets had been manipulated last year.

Table 1.

We have at least partial data for 81 of the 86 voting centers, and in all but 9, the MAS share of the vote has increased when compared to 2019.

In 2019, the OAS and other observers appeared scandalized by the fact that, in many rural areas, Morales had received more than 90 percent of the vote — and in some cases, even 100 percent of the vote. This, they claimed, surely sufficed as evidence of fraud. But, the 2020 results thus far further discredit the unsubstantiated claims made by the OAS, which served as justification for a coup d’etat and the repression that followed. To this day, former electoral officials remain under house arrest based on nothing more than the OAS audit.

As we noted in the March report, the communities targeted in the OAS analysis of these 226 tally sheets are, in the majority of cases, predominantly Indigenous. Though it may come as a shock to see a candidate receive 100 percent of the votes, it shouldn’t. Community voting — in which a community comes to a consensus around who to vote for — is a widely recognized phenomenon in Bolivia.

What the OAS alleged is that electoral jurors, the citizens selected at random by the electoral authorityTSE to serve as electoral officials at each voting table, did not print their names on the tally sheets — but that someone else had written their names. To be clear, the OAS does not allege that all 226 were filled out by the same individual; — in no case does the OAS allege that more than 7 tally sheets were filled out by the same person. Further, in only one of the 226 cases does the OAS allege any problem at all with any signatures on the tally sheets. Rather than fraud, the most likely explanation for this is simply that a notary (each notary oversees about 8 voting tables), or some other official with clear handwriting, printed the names and then each juror signed the tally sheet. It is not clear, from the electoral regulations, that this is even a violation of the electoral law. Either way, the results from 2020 further confirm that there was nothing abnormal about the results on these 226 tally sheets in 2019. Further, what the OAS identified as irregularities had no discernable impact on the results of the election.

We can’t go back to 2019, or erase the racist violence unleashed on the population following the coup. On Sunday, Bolivians showed their courage, and the power of organized social movements, in righting the wrong of 2019. But that victory shouldn’t allow us to forget about 2019, or the role that international actors played in overthrowing a democratically elected government. Those 226 tally sheets never showed fraud, as the OAS asserted. They do, however, reveal how the OAS disenfranchised tens of thousands of Indigenous Bolivians in its galling attempts to justify the undemocratic removal of an elected leader.

Jake Johnston is a Senior Research Associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C.

Arce to Restore Bolivian Relations With Cuba and Venezuela, Blasts OAS

teleSUR – October 21, 2020

Bolivia’s elected president Luis Arce said that he would carry out a foreign policy of restoration of relationships with Venezuela, Cuba, and Iran.

“We are going to reestablish all relations. This government has acted very ideologically, depriving the Bolivian people of access to Cuban medicine, Russian medicine, and advances in China. For a purely ideological issue, it has exposed the population in a way unnecessary and harmful,” Arce explained.

The former Economy Minister, during the 14 years mandate of Indigenous leader Evo Morales, participated in the process of increasing Bolivian’s literacy levels and offering free healthcare to thousands with the support of Cuban doctors. All this social progress was radically paralyzed by the coup born government of Jeanine Añez.

Likewise, Arce emphasized that his government will open the door to all countries based on mutual respect and sovereignty. “Nothing more,” Arce remarked.

On the other hand, the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) leader warned that the Organization of the American States (OAS) has to amend its mistakes in Bolivia. The OAS co-authored the report on the 2019 elections that served as a pretext to coup Evo Morales. This report was later proved to be inaccurate. It has also supported the de facto government of Jeanine Añez, who carried out massacres and sank the country into an unprecedented economic recession.

In this sense, Arce was clear that the “OAS has to make amends for their mistakes. But if it does not, we (the elected government) will work, as well as with other countries, with international organizations that respect us.”

Socialist Presidential Candidate Arce Wins Bolivia’s Elections

Luis Arce and David Choquehuanca celebrate the results of the elections, La Paz, Bolivia, Oct. 19, 2020. | Photo: EFE

teleSUR – October 19, 2020

After midnight on Sunday, Bolivian authorities allowed the results of the exit polls to be known. The Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) presidential candidate Luis Arce obtained 52.4 percent of the votes, the Citizen Community (CC) candidate Carlos Mesa got 31.5 percent, and the “We Believe Alliance” candidate Luis Fernando Camacho reached 14.1 percent of the votes.

Bolivia’s president-elect Arce thanked the people for their support and for their peaceful participation in the electoral process.

“We have recovered democracy and hope. We ratify our commitment to work with social organizations. We are going to build a national unity government.”

Previously, the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) spokesperson Sebastian Mitchell made an official statement regarding the absence of definitive data on the elections. He said that mainstream media and exit-polls companies know that Socialist candidate Arce had already exceeded 45 percent of the votes.

“Election observers do not understand if the absence of information results from inefficiency or if the government is implementing a strategy to win two or three days, generate violence, and justify a military intervention,” Mitchell said.

The Bolivian Socialists’ message was categorical and clear: “we call on the community to avoid provocations… let’s end this nightmare we have been living for a year.”

A few minutes before the official information was issued, former President Evo Morales, who remains a political asylee in Argentina, recalled that millions of Bolivians cast their vote peacefully and demanded that the coup-born regime led by Jeanine Añez respect the results.

“Yesterday we denounced that the authorities suspended the presentation of the results of the exit poll companies. That was suspicious,” the Socialist leader said

“Everything indicates that the MAS has won the elections and won a majority of seats in both chambers,” Evo added.

Luis Arce: ‘We Recovered Democracy and Took Back Our Country’

The winner of Bolivia’s elections Luis Arce Monday celebrated the unofficial results of the quick vote-counting as he said, “we will govern for all, we will redirect the change without hate.”

On Sunday night, Bolivian authorities allowed the results of the exit polls to be presented to the public. There it was observed that the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) won the elections with 53 percent of the votes in its favor. In the second place was the right-wing candidate Carlos Mesa, who got the 30.8 percent of the votes.

Minutes after learning of these results, Arce assured the people that “we will restore unity in our country, and we will recover the economy, step by step.”

In the Socialist headquarters in La Paz, the slogans “We are MAS” were heard repeatedly. In several areas of El Alto, La Paz, and Cochabamba, firecrackers were heard as a sign of celebration.

“I want to thank the Bolivian people for their vote. We will work to recover their hopes and expectations,” said Arce, who was accompanied by Vice-President David Choquehuanca.

MAS Senate candidate Leonardo Loza expressed that “we will not be a government of persecution. But there will be no forgetting or forgiving for those who got killed in Senkata and Sacaba during the 2019 coup.”

“MAS had a resounding victory. We have become millions,” Bolivia’s former President Evo Morales stressed.

The coup-born regime’s leader Jeanine Añez acknowledged MAS’ victory and congratulated the Arce-Choquehuanca binomial for having achieved a majority of the votes.

“We still do not have the official count, but the data shows that MAS won. Congratulations to the winners. I ask them to govern with Bolivia and democracy in mind,” Añez tweeted.

So far, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) official vote count has only processed 15.66 percent of the total votes.

Coups and Neo-Coups in Latin America

By Juan Paz y Miño Cepeda |Venezuelanalysis | September 15, 2020

I recently received an article entitled “Coups and neo-coups in Latin America. Violence and political conflict in the twenty-first century” by Carlos Alberto Figueroa Ibarra, a long-time friend and academic at the University of Puebla, Mexico, and Octavio Humberto Moreno Velador, a professor at the same university.

The authors say that since the 1980s, democracy in Latin America has asserted itself across the continent, so much so that the topic has become recurrent in the political sciences. However, during the first seventeen years of the 21st century, new coups resurfaced, which they describe as “neo-coups.”

During the twentieth century, the authors identified 87 coups in South America and the Caribbean, with Bolivia and Ecuador being the most hit countries, while Mexico has only suffered once. The greatest concentration of coups occurred in four decades: 1930-1939 with 18; 1940-1949 with 12; 1960-1969 with 16 and 1970-1979 with 13. Between 1900-1909 and 1990-1999, the fewest coups occurred (3 and 1, respectively). Finally, 63 coups were deemed as military-led; 7 civilian; 8 civic-military; 6 presidential self-coups and three military self-coups. 77 percent of coups had a marked influence of right-wing ideology and party participation, and since the 1960s US intervention has been observed in several coups.

The neo-coups of the 21st century, however, are different from the coups of the twentieth century and with distinct characteristics. Of the seven studied, four have been carried out by the military/police (two which failed in Venezuela/2002 and Ecuador/2010 and two which were successful in Haiti/2004 and Honduras/2009). Likewise, two were parliamentary coups (Paraguay/2012 and Brazil/2016, both successful) and one was a civilian-state-led coup (Bolivia/2008, failed). In three of them, there is evidence of US intervention (Haiti, Bolivia and Honduras).

The intervention of the military or police took place in Venezuela, Haiti, Honduras and Ecuador. In Haiti, Bolivia and Brazil, large-scale concentrations of opposition citizen groups preceded the coups, exerting political pressure. There were also other cases of subsequent concentrations in support of Presidents Hugo Chávez and Rafael Correa, which prevented the success of the coups against them.

In three cases there was clear intervention by the judiciary (Honduras, against Manuel Zelaya; Paraguay, against Fernando Lugo; and Brazil, against Dilma Rousseff), and also of the legislative powers.

In addition, regional and supranational institutions have intervened in defence of democracy, specifically MERCOSUR, UNASUR, CELAC and even the Rio Group.

The authors conclude that “The new coups have sought to evade their cruder military expression in order to seek success. In this sense, the intervention of judicial and parliamentary institutions have represented a viable alternative to maintaining democratic continuity, despite the breakdown of constitutional and institutional pacts.”

To the analysis carried out by the two professors, and which I summarise without going into too many details, some considerations may be added.

All the coups of the 21st century have been directed against rulers of the Latin American progressive cycle: Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, Manuel Zelaya, Rafael Correa, Fernando Lugo, Dilma Rousseff, and Haiti, where the case is particular because of the turbulence that the country has experienced where the military coup was against Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who had won the election with 91.69 percent of the vote.

Progressive governments aroused furious enemies: business elites, traditional oligarchies, military sectors of old “McCarthyism” anti-communism, the political right, “corporate” media, and, no doubt, imperialism.

There is not a single coup d’état led by “leftist” forces, which reveals an equally new phenomenon: the entire left has accepted democracy as a political system and elections as an instrument through which they may come to power. Historically speaking, this phenomenon represents a continuation of Salvador Allende’s and the Chilean Popular Unity’s thesis, which trusted in the possibility of building socialism through a peaceful path. It is the political and economic right, which have turned to neo-coup mongering, with their discourse of defending “democracy.”

Those same right-wing sectors have not only sponsored “soft coups,” but also promoted the use of two mechanisms that have been tremendously successful to them. Firstly, lawfare, or “legal war,” used to pursue, in appearance of legality, those who have served or identified with progressive governments. Secondly, the use of the most influential media (but also of social media and their “trolls”), which were put at the service of combating “populists” and “progressives,” and defend the interests of persecuting governments, business elites, rich sectors and transnational capital. These phenomena have been clearly expressed in Brazil against Inácio Lula da Silva, Dilma Roussef and the PT Workers’ Party, but also in Bolivia, against Evo Morales and the MAS Movement to Socialism and in Ecuador, where righting forces have achieved the prosecution of Rafael Correa, of figures of his government and of the “correístas.” In Argentina Alberto Fernández’s triumph stopped the legal persecution against Cristina Fernández and “Kirchnerismo”.

But there is, finally, a new element to be added to the neo-coup mongering of the 21st century, which is the anticipated coup d’état. This has been inaugurated in Bolivia and Ecuador.

In Bolivia, not only was the vote count suspended and Evo Morales forced to take refuge outside the country, but [he and his party] have been politically outlawed, and every effort has been made to marginalise them from future elections.

In Ecuador, all kinds of legal ruse have been used to prevent Rafael Correa’s vice-presidential candidacy (he was ultimately not admitted), to not recognise his party and other forces that could sponsor him, as well as to make it difficult for the [Correa-backed] Andrés Araúz team to run for the presidency.

It also has an equally unique characteristic of what happened in Chile. In Chile, despite the protests and social mobilisations, as well as domestic and international political pressure, the political plot was finally manipulated in such a way that the plebiscite convened for October/2020 will not be for a Constituent Assembly (which could dictate a new constitution), but for a Constitutional Convention, which allows traditional forces to preserve their hegemony, according to the analysis carried out by renowned researcher Manuel Cabieses Donoso.

As a result, neo-coup mongering has shown that, while institutional and representative democracy has become a commonplace value and a line of action for the social and progressive lefts, it has also become an instrument that allows access to government and, with it, the orientation of state policies for the popular benefit and not at the service of economic elites.

On the other hand, it has become an increasingly “dangerous” instrument for the same bourgeoisie and internal oligarchy, as well as imperialism, to such an extent that they no longer hold back from breaking with their own rules, legalities, institutions or constitutional principles, using new forms of carrying out coups.

It is, however, an otherwise obvious lesson in Latin American history: when popular processes advance, the forces willing to liquidate them are also prepared. And finally, for these forces, democracy doesn’t matter at all, only saving businesses, private accumulation, wealth and the social exclusiveness of the elites.

Juan J. Paz y Miño Cepeda is an Ecuadorian historian from the PUCE Catholic University of Quito. He is also the former vice-president of the Latin-American and Caribbean Historian’s Association (ADHILAC).

Translation by Paul Dobson for Venezuelanalysis.

Bolivia: La Paz Uses Mobile Crematories as COVID Deaths Increase

Mobile crematory in La Paz, Bolivia. August, 2020. | Photo: Twitter/ @ConElMazoDando

teleSUR | August 13, 2020

Bolivia COVID-19 victim’s relatives use mobile crematories as an alternative to burials after cemeteries collapsed due to the increase in virus-related deaths.

“We wanted to help in this pandemic, and one possibility was showing others how to make a crematory oven. Then we asked ourselves, wouldn’t it be better if it could be mobile, to move it from one place to another?” the environmental engineer and mobile crematory inventor Carlos Ayo says.

The mobile crematory poses an alternative for less advantaged families who cannot dispose of a dignified and sanitary end for their relative’s remains. A cremation with the mobile device costs 40 USD, while the cost of the conventional incinerator reaches 144 USD.

The itinerant crematorium fits in a trailer and uses locally produced liquefied petroleum gas. It can process a corpse in 30 to 40 minutes and about 20 bodies per day.

According to Ayo, several local authorities requested his services as corpses pile up in the streets, and families wait for days to bury their beloved ones.

La Paz Mayor’s Office, one of the cities most harmed by the virus, reported local cemeteries received over 2,000 bodies in July, an atypical figure from the 500 average.

As of Thursday, Bolivia health authorities registered 96,459 COVID-19 cases, 3,884 deaths, and 33,720 recoveries from the virus.

Bolivia general strike exposes Canada’s undemocratic policy

By Yves Engler · August 7, 2020

If Indigenous lives really mattered to the Trudeau Liberals the Canadian government would not treat the most Indigenous country in the Americas the way it has.

Canada’s policy towards Bolivia is looking ever more undemocratic with each passing day. A general strike launched on Monday in the Andean nation is likely to further expose Canada’s backing for the alliance of economic elites, Christian extremists and security forces that deposed Bolivia’s first Indigenous president.

Hours after Evo Morales was ousted in November, foreign affairs minister Chrystia Freeland released a statement noting, “Canada stands with Bolivia and the democratic will of its people. We note the resignation of President Morales and will continue to support Bolivia during this transition and the new elections.” Freeland’s statement had no hint of criticism of Morales’ ouster while leaders from Argentina to Cuba, Venezuela to Mexico, condemned Morales’ forced resignation.

The anti-democratic nature of Canada’s position has grown starker with time. Recently, the coup government postponed elections for a third time. After dragging their feet on elections initially set for January the “interim” government has used the Covid-19 pandemic as an excuse to put off the poll until mid-October. But, the real reason for the latest postponement is that Morales’ long-time finance Minister, Luis Arce, is set to win the presidency in the first round. Coup President Jeanine Áñez, who previously promised not to run, is polling at around 13% and the main coup instigator, Luis Fernando Camacho, has even less popular support. To avoid an electoral drubbing, the coup government has sought to exclude Morales’ MAS party from the polls.

After ousting Morales the post-coup government immediately attacked Indigenous symbols and the army perpetrated a handful of massacres of anti-coup protesters. The unconstitutional “caretaker” regime shuttered multiple media outlets and returned USAID to the country, restarted diplomatic relations with Israel and joined the anti-Venezuela Lima Group. They also expelled 700 Cuban doctors, which has contributed to a surge of Covid-19 related deaths. In a recent five day period Bolivia’s police reported collecting 420 bodies from streets, houses, or vehicles in La Paz and Santa Cruz.

The pretext for Morales’ overthrow was a claim that the October 20, 2019 presidential election was flawed. Few disputed that Morales won the first round of the poll, but some claimed that he did not reach the 10% margin of victory, which was the threshold required to avoid a second-round runoff. The official result was 47.1 per cent for Morales and 36.5 per cent for US-backed candidate Carlos Mesa.

Global Affairs Canada bolstered right-wing anti-Morales protests by echoing the Trump administration’s criticism of Morales’ first round election victory. “It is not possible to accept the outcome under these circumstances,” said a Global Affairs statement on October 29. “We join our international partners in calling for a second round of elections to restore credibility in the electoral process.”

At the same time, Trudeau raised concerns about Bolivia’s election with other leaders. During a phone conversation with Chilean president Sebastián Piñera the Prime Minister criticized “election irregularities in Bolivia.” Ottawa also promoted and financed the OAS’ effort to discredit Bolivia’s presidential election.

After the October 20 presidential poll, the OAS immediately cried foul. The next day the organization released a statement expressing “its deep concern and surprise at the drastic and hard-to-explain change in the trend of the preliminary results [from the quick count] revealed after the closing of the polls.” Two days later they followed that statement up with a preliminary report that repeated their claim that “changes in the TREP [quick count] trend were hard to explain and did not match the other measurements available.”

But, the “hard-to-explain” changes cited by the OAS were entirely expected, as detailed in the Washington-based Centre for Economic Policy Research’s report “What Happened in Bolivia’s 2019 Vote Count? The Role of the OAS Electoral Observation Mission”. The CEPR analysis pointed out that Morales’ percentage lead over the second place candidate Carlos Mesa increased steadily as votes from rural, largely Indigenous, areas were tabulated. Additionally, the 47.1% of the vote Morales garnered aligned with pre-election polls and the vote score for his MAS party.

Subsequent investigations have corroborated CEPR’s initial analysis. A Washington Post commentary published by researchers at MIT’s Election Data and Science Lab was titled “Bolivia dismissed its October elections as fraudulent. Our research found no reason to suspect fraud.” More recently, the New York Times reported on a study by three other US academics suggesting the OAS audit was flawed. The story noted, “a close look at Bolivian election data suggests an initial analysis by the OAS that raised questions of vote-rigging — and helped force out a president — was flawed.”

But, the OAS’ statements gave oxygen to opposition protests. Their unsubstantiated criticism of the election was also widely cited internationally to justify Morales’ ouster. In response to OAS claims, protests in Bolivia and Washington and Ottawa saying they would not recognize Morales’s victory, the Bolivian president agreed to a “binding” OAS audit of the first round of the election. Unsurprisingly the OAS’ preliminary audit report alleged “irregularities and manipulation” and called for new elections overseen by a new electoral commission. Immediately after the OAS released its preliminary audit US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo went further, saying “all government officials and officials of any political organizations implicated in the flawed October 20 elections should step aside from the electoral process.” What started with an easy-to-explain discrepancy between the quick count and final results of the actual counting spiraled into the entire election is suspect and anyone associated with it must go.

At a Special Meeting of the OAS Permanent Council on Bolivia the representative of Antigua and Barbuda criticized the opaque way in which the OAS electoral mission to Bolivia released its statements and reports. She pointed out how the organization made a series of agreements with the Bolivian government that were effectively jettisoned. A number of Latin American countries echoed this view. For his part, Morales said the OAS “is in the service of the North American empire.”

US and Canadian representatives, on the other hand, applauded the OAS’ work in Bolivia. Canada’s representative to the OAS boasted that two Canadian technical advisers were part of the audit mission to Bolivia and that Canada financed the OAS effort that discredited Bolivia’s presidential election. Canada was the second largest contributor to the OAS, which received half its budget from Washington. In a statement titled “Canada welcomes results of OAS electoral audit mission to Bolivia” Freeland noted, “Canada commends the invaluable work of the OAS audit mission in ensuring a fair and transparent process, which we supported financially and through our expertise.”

A General strike this week in Bolivia demanding elections take place as planned on September 6 will put Canadian policy to the test.

US-Backed Coup Gov’t in Bolivia Suspends Elections for Third Time

By Alan Macleod | MintPress News | July 24, 2020

Amid a rapidly worsening COVID-19 pandemic, Bolivia’s coup government has once again suspended much-anticipated elections that were due to be held on September 6. This is the third time the administration of Jeanine Añez has postponed them because of the virus, setting a new date for October 18.

The move has drawn condemnation from both left and right, but for different reasons. MintPress’ Ollie Vargas, who covered events from inside the country since last year’s November 10 coup, was dismayed, announcing:

Bolivia’s unelected coup regime has extended it’s illegitimate power by canceling elections once again. When we get to October they’ll invent another reason to postpone, then another, till they’ve found a buyer for the lithium & other natural resources. This is a dictatorship.

Former President Evo Morales of the Movement to Socialism (MAS) party agreed, stating that “The de facto government wants to gain more time to continue the persecution of social leaders and against MAS candidates. It’s yet another form of persecution. That’s why they don’t want elections on September 6.” Meanwhile, coup leader Fernando Camacho rejected the new date, demanding elections be scrapped altogether, a position shared by the far-right Santa Cruz “Civic Committee.”

Morales was reelected in October for another five year term. A popular president, he reduced poverty by half and extreme poverty by three quarters, while increasing the (inflation-adjusted) per capita GDP by 50 percent in his 13 years in office. He managed this primarily through a series of nationalizations of the country’s key industries and by expelling the predatory International Monetary Fund (IMF) from Bolivia. But in November, the military and police intervened, demanding he resign. Today he lives in exile in Argentina. Nevertheless, the latest polls show that the MAS candidate Luis Arce, who served as Morales’ finance minister, would win the election outright on the first ballot if it were held today. Arce accused Añez of using the pandemic as a pretext to extend her rule.

From popular mandate to elitist candidate

A little-known senator from a party that received only just four percent of the vote in October, Añez was handpicked by the military to become the new president. A strongly Christian conservative who described the country’s indigenous majority as “satanic,” she arrived to take her new place in government clutching an oversized bible. She enjoyed the support of the country’s elite, the U.S. government, and the entire spectrum of corporate media, who cheered the events as they happened. The new administration immediately began to suppress and criminalize dissent, including massacring protesters who objected to the takeover. Despite leading in the polls, the MAS have been suppressed, with many of their leaders jailed or facing dubious charges. Morales himself faces life in prison for “terrorism” if he sets foot in his country again.

Añez has also overseen the selling off of the country’s national resources, including in the hydrocarbon industry, and has completely reoriented its foreign policy to align with the United States. She has also begun working with the IMF, taking out a $327 million loan in April. The U.S. government strongly backed Añez from the beginning; three days after the coup the State Department released an official communiqué “applauding” her for “leading her nation” through a “democratic transition.”

The stated reason for the postponement of the elections is the country’s continued inability to deal with the coronavirus pandemic. Supreme Electoral Tribunal President Salvador Romero said the move was necessary to keep Bolivia’s hospitals and cemeteries from collapsing under the strain of the increased deaths. “This election requires the highest possible health security measures to protect the health of Bolivians,” he said. One reason why the country’s medical system is under such pressure is that Añez expelled hundreds of Cuban doctors working primarily with the country’s poorest people, leading to closures of hospitals and health clinics. While Bolivia has officially reported 65,000 cases and 2,407 deaths, some believe those figures could be an underestimate. This week, police said they recovered 420 dead bodies from streets, vehicles and homes in La Paz and Santa Cruz. In June, Añez herself tested positive for COVID-19.

In response to the delayed elections, Bolivian trade unions have given the government 72 hours to reverse the decision, threatening “indefinite mobilizations” to restore democracy. Thus, it appears that even after eight months of constant political struggle, tensions could be about to be increased once again.

Alan MacLeod is a Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent.

NYT Acknowledges Coup in Bolivia—While Shirking Blame for Its Supporting Role

If the New York Times (6/7/20) has had second thoughts about its coverage of the 2019 Bolivian election and subsequent coup, it hasn’t shared them with its readers.

By Camila Escalante with Brian Mier | FAIR | July 8, 2020

The New York Times (6/7/20) declared that an Organization of American States (OAS) report alleging fraud in the 2019 Bolivian presidential elections—which was used as justification for a bloody, authoritarian coup d’etat in November 2019—was fundamentally flawed.

The Times reported the findings of a new study by independent researchers; the Times brags of contributing to it by sharing data it “obtained from Bolivian electoral authorities,” though this data has been publicly available since before the 2019 coup.

The article never uses the word “coup”—it says that President Evo Morales was “push[ed]…from power with military support”—but it does acknowledge that “seven months after Mr. Morales’s downfall, Bolivia has no elected government and no official election date”:

A staunchly right-wing caretaker government, led by Jeanine Añez… has not yet fulfilled its mandate to oversee swift new elections. The new government has persecuted the former president’s supporters, stifled dissent and worked to cement its hold on power.

“Thank God for the New York Times for letting us know,” must think at least some casual readers, who trust the paper’s regular criticism of rising authoritarianism within the US—perhaps adding, “Well, I guess it’s too late to do anything about Bolivia now.”

The fact is, the Times has been patting itself on the back for acknowledging authoritarianism in neofascist regimes that it helped normalize in Latin America for at least 50 years. The only surprise to readers who are aware of this ugly truth is that this time it took so long.

It only took the Times 15 days and the arrest of 20,000 leftists, for example, to counter nine articles supportive of the April 1, 1964, Brazilian military coup (Social Science Journal, 1/97) with a warning (4/16/64) that “Brazil now has an authoritarian military government. ” As was the case with Brazil in 1964, recognizing that Bolivia has now succumbed to authoritarianism may help the New York Times’ image with progressive readers, but it doesn’t do anything for the oppressed citizens of the countries involved.

While the coup was unfolding, and when Northern solidarity for Bolivia’s Movement for Socialism government (MAS in Spanish) might have helped avert disaster, the New York Times was whistling a different tune. The day after Morales’ re-election (10/21/19), it portrayed the paramilitary putschists who were carrying out violent threats against elected officials and their families as victims of repressive police actions perpetrated by the socialist government. “Opponents of Mr. Morales angrily charged ‘fraud, fraud!’” read the post-election article:

Heavily armed police officers were deployed to the streets, where they clashed with demonstrators on Monday night, according to television news reports.

One day after Morales was removed from power, the Times (11/11/19) engaged in victim-blaming, with a news analysis headlined ‘This Will Be Forever’: How the Ambitions of Evo Morales Contributed to His Fall.” The first Indigenous president in Latin American history was not being deposed illegally, after winning a fair election, by groups of armed paramilitary thugs, amid threats of murder and rape to his family members, the Times implied; rather, he was being brought down due to his own character faults as a Machiavellian back-stabber.

I arrived in Bolivia on November 13, 2019, shortly after Jeanine Añez’ unconstitutional swearing in as unelected, interim president, on a cartoonishly oversized Bible. I was there as a reporter for MintPress News and teleSUR, and two of the active sites I reported from were in the most militantly MAS-dense areas: In Sacaba, where the coup regime’s first massacre took place on November 15, and in El Alto, where the Senkata massacre took place on November 19.

The third, and most extensively covered, resistance to the coup was in the heart of the city of La Paz, where daily protests were staged. Beyond these major conflict areas, there were large mobilizations in Norte Potosí, the rural provinces of the department of La Paz, Zona Sud of Cochabamba, Yapacani and San Julian. The vast majorities within all rural areas across the country were also in deep resistance to the coup.

The November coup represented the ousting of a government deeply embedded in the country’s Indigenous campesino and worker movements, by internal colonial-imperialist actors, led in large part by Bolivia’s fascist and neoliberal opposition sectors, most notably Luis Fernando Camacho and Carlos Mesa, who received ample support from the US government and the far-right Bolsonaro administration of Brazil. The Indigenous and social movement bases resisting the coup were deeply distrusting of Bolivian media, which they immediately deemed as having played a key role in it.

Those same groups that were hostile towards major Bolivian news networks and journalists lined up to be heard by myself and those who accompanied me, once they recognized my teleSUR press credentials. One woman attending a cabildo (mass meeting) of the Fejuves (neighborhood organizations) of El Alto detailed how her workplace, Bolivia TV, had been attacked by right-wing mobs as the coup authorities got rid of those deemed sympathizers of the constitutional government, replacing them by force almost immediately.

Indigenous Bolivian communities were at the very forefront of the protests and resistance actions against the coup, namely the blocking of key highways and roads, as in the case of Norte Potosí, the blocking of the YPFB gas plant in Senkata, and 24-hour camps blocking the entry to the Chapare province. La Paz was militarized, making it impossible to get near Plaza Murillo, the site of the Presidential Palace and the Congress. I witnessed daily violent repression by security forces against those who gathered in protest near the perimeter of the Plaza, including unions and groups such as the Bartolina Sisa Confederation, a nationwide organization of Indigenous and campesina women, and the highly organized neighborhood associations of El Alto.

One might think this kind of grassroots, pro-democracy mobilization coordinated by working-class people against an authoritarian takeover would be the type of thing the New York Times would applaud. After all, it ran over 100 articles championing Hong Kong’s protesters in the last six months of 2019 alone.

Anatoly Kurmanaev, author of this New York Times piece (12/5/19) that ignored real-time critiques of the OAS’s complaints about the Bolivian election, was a co-author of the piece (6/7/20) acknowledging that some have “second thoughts” about the OAS attacks on Evo Morales.

As resistance grew on the streets of Bolivia, however, the New York Times only continued the rationalization of the unconstitutional, authoritarian taking of power, using the now-discredited OAS report to do so.

“Election Fraud Aided Evo Morales, International Panel Concludes,” read a December 5 article—one of several the paper ran discrediting the democratic electoral process. Like the others, it failed to challenge dubious claims by the right-wing coalition in charge of the OAS—which received $68 million, or 44% of its budget, from the Trump administration in 2017—that Evo Morales was elected via “lies, manipulation and forgery to ensure his victory.”

A newspaper that prides itself on showing the full picture could have cited the debunking of the OAS study conducted by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), an organization with two Nobel Laureate economists on its board, whose co-director Mark Weisbrot has written over 20 op-ed pieces for the New York Times. Even before the coup, CEPR (11/8/19) published an analysis of the Bolivian vote that concluded, “Neither the OAS mission nor any other party has demonstrated that there were widespread or systematic irregularities in the elections of October 20, 2019.”

The fatal flaws in the report the OAS used to subvert a member government, long obvious, are now undeniable even to the New York Times. But the paper still hasn’t acknowledged, let alone apologized for, the credulous reporting that gave it a leading role in bringing down an elected president and the violence that followed.

Bolivia’s Struggle to Restore Democracy after OAS Instigated Coup

By Frederick B. Mills, Rita Jill Clark-Gollub, Alina Duarte | Council on Hemispheric Affairs | July 9, 2020

On October 21, 2019, the Organization of American States (OAS) issued a fateful communique on the presidential elections in Bolivia: “The OAS Mission expresses its deep concern and surprise at the drastic and hard-to-explain change in the trend of the preliminary results revealed after the closing of the polls.”[1] The mission’s report came in a highly polarized political context. Rather than wait for a careful and fair-minded analysis of the election results, it raised unsubstantiated doubts about the legitimacy of President Evo Morales’ lead as some of the later vote tallies were being reported. This was a bombshell report at a time when it appeared that Morales had garnered a sufficient margin of victory over his right wing opponent, Carlos Mesa, to avoid a runoff election.

The manufactured electoral fraud was quickly debunked by experts in the field. Detailed analyses of the election results were conducted by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR)[2] and Walter R. Mebane, Jr., professor of Political Science and Statistics at the University of Michigan in early November 2019.[3] These were later corroborated by researchers at MIT’s Election Data and Science Lab[4] and more recently by an article published by the New York Times[5] featuring the study of three academics: Nicolás Idrobo (University of Pennsylvania), Dorothy Kronick (University of Pennsylvania), and Francisco Rodríguez (Tulane University)[6].

All of these professional and academic analyses found the charges of fraud by the OAS to have been unfounded.

The OAS electoral mission, however, had already poisoned the well. The false narrative of electoral fraud gave ammunition to anti-Bolivarian forces in the OAS and the right wing opposition inside Bolivia to contest the outcome of the election and go on the offensive against Morales and his party, the Movement Towards Socialism (Movimiento al Socialismo, MAS). During a three-week period, a right wing coalition led protests over the alleged electoral fraud, while pro-government counter protesters defended the constitutional government. The military and police cracked down on the pro-Morales protesters, while showing sympathy for right wing demonstrators. Then, on November 10, 2019, in its “Electoral integrity analysis,” the OAS doubled down on its dubious claims, impugning “the integrity of the results of the election on October 20, 2019.”[7]

The track record of the OAS electoral mission, which was invited to observe and assess the election by the Bolivian government of Evo Morales, had already been stained by its 2015 debacle in Haiti.[8] In the case of Bolivia, the mission politicized election results and set the stage for murder by a coup regime. It appears that there is not much political daylight between the judgment of the OAS electoral commission and the rabidly anti-Bolivarian OAS Secretary, Luis Almagro. Far from finding that the coup against Morales constituted a breach in the democratic order of Bolivia, the OAS simply exploited its position as arbiter of the election to rally behind the right wing coup leaders.

Morales resigns and a “de facto” right wing regime unleashes a wave of repression

Despite the relentless drive by Washington against Bolivarian governments in the region, President Morales was apparently unprepared for the disloyalty within his security forces and he was caught off guard by the OAS propensity to serve US interests in the region. MAS activists, legislators, union activists, Indigenous organizations, and social movement activists, however, continued to resist the coup even as they faced arrest and violence from the de facto regime.

The coup forces exercised extreme violence against authorities of the Morales’ administration and MAS legislators (the majority of Congress). Several houses were burned down and some relatives of authorities were kidnapped and injured, all with total impunity and without protection by the security forces.[9]

With the OAS-instigated coup gaining traction within the security forces and police, as well as Morales’ political adversaries, the President chose the path of accommodation. He offered to reconstitute the electoral authority and hold fresh elections. This concession to OAS authority was met by calls from the police and military for his resignation. Rather than launch a campaign of resistance from the MAS stronghold of Chapare, Morales resigned his post, opting for exile in an unsuccessful bid to avoid further bloodshed. Jeanine Áñez, an opposition party senator with Plan Progreso para Bolivia Convergencia Nacional, proclaimed herself President after the resignation of Senate President Adriana Salvatierra, who refused to legitimize the coup with an unjustified “succession.”[10]

The scenes in the streets of Cochabamba turned ugly. It was a field day for racist attacks on the majority Indigenous population. The Indigenous flag–the wiphala–was burned in the streets, and much fanfare was made when Áñez, surrounded by right wing legislators, held up a large leather bible and declared, “The Bible has returned to the palace.” Such attempts to resubordinate Bolivia’s plurinational heritage were met with widespread resistance.

Workers of all industries and sectors continue protests against Áñez and to protect social rights created under Morales’s government (photo credit: MAS-IPSP, http://www.masipsp.bo).

After thirteen years of impressive economic growth, poverty reduction, recovery of the nation’s natural resources, and the inclusion of formerly marginalized sectors in the political life of the country under the leadership of President Evo Morales, Bolivia had now suffered an enormous blow to the liberatory project of the 2009 Constitution. But the coup fit perfectly into the US-OAS drive to recolonize the Americas.

Secretary General Luis Almagro, who would never let an opportunity to attack the Bolivarian cause go to waste, immediately recognized self-proclaimed President, Senator Jeanine Áñez, adding yet one more crime to the long list from his shameful tenure at the OAS.[11] At a special meeting of the OAS on November 12, 2020 Almagro declared, “There was a coup in the State of Bolivia; it happened when an electoral fraud gave the triumph to Evo Morales in the first round.”[12]

During the meeting, 14 member states of the OAS (Argentina, Brasil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, the US, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, Peru) and the unelected US-backed shadow government of Venezuela called for new elections in Bolivia “as soon as possible,” while Mexico, Uruguay and Nicaragua warned against the precedent being set by the “coup” against Evo Morales. The ambassador of Mexico to the OAS, Luz Elena Baños, described the coup against Morales as “a serious breach in the constitutional order by means of a coup d’etat,” adding “the painful days when the Armed Forces sustained and deposed governments ought to remain in the past.” [13] The Trump administration echoed Almagro’s declaration and moved quickly to endorse what was now a “de facto” government.[14] The OAS was now at the service of two unelected, US-backed, self-proclaimed presidents (Juan Guaidó for Venezuela and Jeanine Áñez for Bolivia).

What followed was the brutal repression of widespread protests amid grass roots clamor for the return of President Morales,[15] who, from his exile in Mexico and later Argentina, still held great clout among rank and file MAS militants and the popular movements. The horrific massacre in Sacaba, on November 15, followed by a massacre in Senkata, on November 19, carried out by the security forces, exposes the coup regime to future prosecution for crimes against humanity.[16] Rather than pacify the country, the repression only galvanized the MAS, which still held a majority in the legislature, as well as the peasant unions and grassroots organizations in their struggle to restore Bolivian democracy. There was indeed a coup, but it had not and still has not been consolidated.

New elections could be compromised by lawfare

Today, Bolivia stands at a crossroads. In June 2020, popular calls were mounting for new elections and the restoration of democracy, despite the ongoing repression. In response to this pressure, on June 22, Áñez signed off on legislation to hold new elections in September. Former president Carlos Mesa (2003-2005) of the right wing Citizens Community Party would face off against the MAS candidate, former Minister of Finance (2006-2019), Luis Arce. Áñez’s decision drew the ire of Minister of Government, Arturo Murillo, who characterizes the most popular political party in the country as narco-terrorist. Murillo even threatened MAS legislators with arrest if they refused to approve promotions for the very military officials responsible for the repression.[17]

Should democratic elections prevail, recent polls do not look good for the “de facto” regime. In a poll taken by CELAG between June 13 and July 3, the MAS candidate, Luis Arce, leads with 41.9% support, followed by Carlos Mesa, with 26.8%, and Áñez, with 13.3%.[18]

Luis Arce, from the MAS party, leads the presidential race in Bolivia (Source: CELAG, https://www.celag.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/panorama-politico-y-social-bolivia-web-2.pdf)

Although Áñez initially said she would not run for president,[19] she later decided to do so even over the objections of her fellow opposition members.[20] The latter said that this went against her purported objective of only serving as a transition government until new elections could be held—initially on May 3, but later canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only was Áñez never a favorite in the polls, her de facto government has been unrelenting in its attempts to persecute the MAS and kick it out of the race.

On March 30 a government oversight agency (Gestora Pública de Seguridad Social de Largo Plazo) filed formal charges against MAS presidential candidate Luis Arce for “economic damages to the State” while he was Minister of Finance. According to the Bolivian Information Agency, his alleged crimes are linked to the contracting of two foreign companies to provide software for the administration of the national pension system.[21]

The charges state that the previous administration paid US$3 million as an advance for a contract valued at US$5.1 million to the Panamanian company Sysde International Inc. However, said company never delivered the software. Consequently, the MAS administration contracted the Colombian company Heinsohn Business Technology for US$10.4 million, on top of which payments were to be made of US$1.6 million annually for the license and source code.

Luis Arce responded to the charges during a press conference,[22] stating that during his tenure, “We entered into a contract for a system and the company failed us, so we filed suit against the company.” But he stressed that the charges simply seek to disqualify the MAS to prevent the party from participating in the presidential election.

Evo Morales took to Twitter to say, “The imminent electoral defeat of the de facto government is leading it to trump up new charges against the MAS-IPSP every day. Now, as we have denounced, they have filed charges based on false conjecture against our candidate to ban him from running for office because he is leading in the polls.”[23]

On July 6, the Attorney General of Bolivia charged Evo Morales himself. The charges are terrorism and financing of terrorism coordinated from exile, and preventive detention has been requested. This is a rehashing of similar charges brought last November, charges denied by Morales.[24]

The persecution against the overthrown government has not stopped. Seven former officials remain asylees at the Mexican Embassy in La Paz: the former Minister of the Presidency, Juan Ramón Quintana Taborga; the former Minister of Defense, Javier Zavaleta; the former government minister, Hugo Moldiz Mercado; the former Minister of Justice, Héctor Arce Zaconeta; the former Minister of Cultures, Wilma Alanoca Mamani; the former governor of the Department of Oruro, Víctor Hugo Vásquez; and the former director of the Information Technology Agency, Nicolás Laguna.

The current Minister of Government, Arturo Murillo, affirmed upon assuming power that the authorities of the constitutional government of Evo Morales would be “hunted” and imprisoned before any arrest warrant was issued.[25] And now, eight months after the coup d’etat, the de facto government has refused to deliver safeguards to the asylum seekers at the embassy even though Bolivia and Mexico are parties to the American Convention on Human Rights, which in its article 22 establishes the right to seek and receive asylum[26].

Calls for free and fair elections without subversion by the OAS

The consequences of the OAS’ bad faith monitoring of the 2019 Bolivian election cannot be overstated. Not only were lives lost in the chaos and violence spurred by the statements of the OAS Electoral Observation Mission, which also resulted in scores of injuries and detentions. But the de facto regime continues its reign of terror, even repressing people protesting hunger during the pandemic lockdown,[27] while it dismantles the extensive social programs put into place during the years of MAS government.[28] Despite the repression, grassroots social movements in Bolivia, most notably peasant and Indigenous women who have bravely withstood attacks by the de facto regime, continue to insist on true democracy. They are inspired by the 2009 Constitution creating the Plurinational State, with its promise of a “democratic, productive, peace-loving and peaceful Bolivia, committed to the full development and free determination of the peoples.”[29]

Indigenous women have been at the forefront of the fight to restore democracy in Bolivia (photo credit: MAS-IPSP, http://www.masipsp.bo).

On July 8, the MAS-IPSP “categorically” rejected the participation of an OAS electoral mission for the September presidential election, on account of their responsibility for the coup against the constitutional government.[30] The communique declared that “it is not ethical for [the OAS electoral mission] to participate again for having been part of and complicit with a coup against the democracy and Social State of Constitutional Law of Bolivia”, and “that [the OAS] is not an impartial organization to defend and guarantee peace, democracy and transparency, but rather a sponsor of petty interests that are foreign to the democratic will of the Bolivian people.” [31]

Bolivia is at a crossroads. Will the de facto regime of Jeanine Áñez, having completed a coup and in command of the security forces, allow a return to democratic procedures to resolve political differences? Or will she join her Minister of Government, Arturo Murillo, in seeking to undermine, through political persecution and lawfare, any chance that the MAS ticket will be on the ballot, let alone allow free elections to take place?

The condemnation of the coup by Mexico, Nicaragua and Uruguay on November 12 was just the start of international solidarity with the call for a return to democracy in Bolivia. On November 21, 31 US organizations denounced “the civic-military coup in Bolivia.” [32] On June 29, 2020 the Grupo de Puebla, a forum that convenes former presidents, intellectuals, and progressive leaders of the Americas, released a statement condemning the actions of the OAS. “The Puebla Group considers that what happened in Bolivia casts serious doubts on the role of the OAS as an impartial electoral observer in the future.”[33] The international community can honor the clamour for free and fair elections in Bolivia by condemning the de facto regime’s use of political persecution and lawfare, supporting democratic elections in September, and rejecting any further role of the OAS in monitoring elections in the Americas.

Patricio Zamorano provided editorial support and research for this article.

Translations from Spanish to English are by the authors.

Luis Arce, presidential candidate, and David Choquehuanca, running for the vice-presidency. They lead all surveys so far (photo credit: MAS-IPSP, http://www.masipsp.bo/).

End notes

[1] “Statement of the OAS Electoral Observation Mission in Bolivia,” https://www.oas.org/en/media_center/press_release.asp?sCodigo=E-085/19

[2] “What Happened in Bolivia’s 2019 Vote Count?” https://cepr.net/report/bolivia-elections-2019-11/

[3] “Evidence Against Fraudulent Votes Being Decisive in the Bolivia Election,” http://www-personal.umich.edu/~wmebane/Bolivia2019.pdf

[4] “Bolivia dismissed its October elections as fraudulent. Our research found no reason to suspect fraud,” https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/02/26/bolivia-dismissed-its-october-elections-fraudulent-our-research-found-no-reason-suspect-fraud/

[5] “New York Times Admits Key Falsehoods that Drove Last Year’s Coup in Bolivia: Falsehoods Peddled by the US, its Media, and the Times,” https://theintercept.com/2020/06/08/the-nyt-admits-key-falsehoods-that-drove-last-years-coup-in-bolivia-falsehoods-peddled-by-the-u-s-its-media-and-the-nyt/. See also the study by CELAG, “Sobre la OEA y las elecciones en Bolivia”, (Nov. 19, 2019). CELAG conducted a study of both the OAS report and CEPR’s analysis and concluded: “The findings of the analysis allow us to affirm that the preliminary report of the OAS does not provide any evidence that could be definitive to demonstrate the alleged “fraud” alluded to by Secretary General, Luis Almagro, at the Permanent Council meeting held on November 12 . On the contrary, instead of sticking to a technically grounded electoral audit, the OAS produced a questionable report to induce a false deduction in public opinion: that the increase in the gap in favor of Evo Morales in the final section of the count was expanding by fraudulent causes and not by the sociopolitical characteristics and the dynamics of electoral behavior that occur between the rural and urban world in Bolivia.” https://www.celag.org/sobre-la-oea-y-las-elecciones-en-bolivia/

[6] “Do Shifts in Late-Counted Votes Signal Fraud? Evidence From Bolivia,” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3621475

[7] “Preliminary Findings Report to the General Secretariat,” http://www.oas.org/documents/eng/press/Electoral-Integrity-Analysis-Bolivia2019.pdf

[8] “Elections in Haiti pose post-electoral crisis, by Clément Doleac and Sabrina Hervé, Dec. 10, 2015. COHA. https://www.coha.org/elections-in-haiti-pose-post-electoral-crisis/

[9] “El Grupo de Puebla rechazó el golpe contra Evo Morales y se solidarizó con el pueblo boliviano,” https://www.infonews.com/el-grupo-puebla-rechazo-el-golpe-contra-evo-morales-y-se-solidarizo-el-pueblo-boliviano-n281357

[10] “Salvatierra: Mi renuncia fue coordinada con Evo y Alvaro,” https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.paginasiete.bo/nacional/2020/1/24/salvatierra-mi-renuncia-fue-coordinada-con-evo-alvaro-244454.html&sa=D&ust=1593696030403000&usg=AFQjCNE_kAMqtAOBGCXdjJV5nkBsfQEWPQ

[11] “Almagro: Evo Morales fue quien cometió un “golpe de Estado,” DW. https://www.dw.com/es/almagro-evo-morales-fue-quien-cometi%C3%B3-un-golpe-de-estado/a-51218739

[12] https://twitter.com/oas_official/status/1194389549037830145?lang=en

[13] “La OEA y la crisis en Bolivia: un choque de relatos irreconciliables”, EFE, Nov. 12, 2019. https://www.efe.com/efe/usa/politica/la-oea-y-crisis-en-bolivia-un-choque-de-relatos-irreconciliables/50000105-4109588

[14] “Statement from President Donald J. Trump Regarding the Resignation of Bolivian President Evo Morales,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-donald-j-trump-regarding-resignation-bolivian-president-evo-morales/

[15] “With the Right-wing coup in Bolivia nearly complete, the junta is hunting down the last remaining dissidents,” https://thegrayzone.com/2019/11/27/right-wing-coup-bolivia-complete-junta-hunting-dissidents/

[16] “Brutal Repression in Cochabamba, Bolivia: So far nine killed, scores wounded,” COHA. https://www.coha.org/brutal-repression-in-cochabamba-bolivia-november-15-2019/

[17] “Bolivian regime threatens to imprison lawmakers, officials,” https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Bolivian-Regime-Threatens-to-Imprison-Lawmakers-Officials-20200524-0004.html

[18] “Encuesta Bolivia, July 2020”, CELAG, https://www.celag.org/encuesta-bolivia-julio-2020/

[19] “Evo Morales busca un candidato y Añez dice que no participará en elecciones”, https://www.lavoz.com.ar/mundo/evo-morales-busca-un-candidato-y-anez-dice-que-no-participara-en-elecciones

[20] “A Jeanine Añez hasta los aliados le critican su candidatura”, https://www.pagina12.com.ar/244221-a-jeanine-anez-hasta-los-aliados-le-critican-su-candidatura

[21] Gestora Pública denuncia formalmente al exministro Luis Arce por daño económico al Estado” https://www1.abi.bo/abi_/?i=452014

[22] “Luis Arce asegura que la denuncia en su contra busca inhabilitar su participación en las elecciones”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DYvPUk643w

[23] “Fiscalía boliviana acusa de terrorismo a Evo Morales.” https://www.eltiempo.com/mundo/latinoamerica/fiscalia-boliviana-acusa-de-terrorismo-a-evo-morales-515054

[24] “Fiscalía boliviana acusa a Morales de terrorismo y pide su arresto,” https://www.hispantv.com/noticias/bolivia/470654/anez-morales-terrorismo-detencion

[25] “¿Quién es Arturo Murillo?”, https://www.pagina12.com.ar/239232-quien-es-arturo-murillo

[26] “American Convention on Human Rights,” https://www.cidh.oas.org/basicos/english/basic3.american%20convention.htm

[27] “Valiente resistencia en K’ara K’ara enfrenta represión policial y militar”, https://www.laizquierdadiario.com/Valiente-resistencia-en-K-ara-K-ara-enfrenta-represion-policial-y-militar

[28] “Bolivia’s Coup President has Unleashed a Campaign of Terror,” https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/05/bolivia-coup-jeanine-anez-evo-morales-mas

[29] “Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Constitution of 2009,” https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Bolivia_2009.pdf

[30] MAS-IPSP tweet, July 8, rejecting OAS mission for September elections.

[31] “El MAS rechaza observadores de la OEA en elecciones bolivianas,” July 9, Telesur. https://www.telesurtv.net/news/bolivia-movimiento-socialismo-rechazo-observadores-oea-20200709-0002.html

[32] “31 US organizations denounce the brutal repression in Bolivia,” COHA. https://www.coha.org/31-us-organizations-denounce-the-brutal-repression-in-bolivia/

[33] ttps://www.telesurtv.net/news/grupo-puebla-rechaza-oea-observador-internacional-20200629-0085.html

Twitter Targets Accounts of MintPress and Other Outlets Covering Unrest in Bolivia

By Alan Macleod | MintPress News | June 29, 2020

Social media giant Twitter took the step of suspending the official account of MintPress News on Saturday. Without warning, the nine-year-old account with 64,000 followers was abruptly labeled as “fake” or “spam” and restricted. This move is becoming a frequent occurrence for alternative media, especially those that openly challenge U.S. power globally.

Immediately preceding the ban, MintPress had been sharing stories about Israeli government crimes against Palestinians, the Saudi-led onslaught in Yemen (both funded and supported by Washington), and about activists challenging chemical giant Monsanto’s latest plans. However, MintPess correspondent Ollie Vargas, stationed in Bolivia and covering the coup and other events there, had another theory on the suspension. Vargas noted that his account, along with union leader Leonardo Loza and independent Bolivian outlets Kawsachun Coca and Kawsachun News were all suspended at the same time. “There was a coordinated takedown of numerous users & outlets based in Chapare, Bolivia. Thousands of fake accounts appeared after the coup. We believe they’re being mobilized to mass report those who criticize the regime,” he said. Since the November coup, Bolivia has been the sight of intense political struggle, with MintPress one of the only Western outlets, large or small, extensively covering the situation (and from a perspective that directly challenges the official US government line). Vargas added that all those accounts suspended appeared in his Twitter bio.

In December, MintPress reported how the strongly conservative Bolivian elite is treating social media as a key battleground in pushing the coup forward, with over 5,000 accounts created on the day of the insurrection tweeting using pro-coup hashtags. With the new administration still lacking both legitimacy and public support, it appears the next step is to simply silence dissenting voices online like they have been silenced inside the country. Kawsachun Coca and Kawsachun News, located in the Chapare region, still not under government control, are among the only remaining outlets critical of the Añez administration.

As Twitter has developed into a worldwide medium of communication, it has also grown an increasingly close relationship with Western state power. In September, a senior Twitter executive was unmasked as an active duty officer in a British Army brigade whose specialty was online and psychological warfare. It was almost entirely ignored by corporate media; the one and only journalist at a major publication covering the story was pushed out of his job weeks later. Earlier this month, Twitter announced it worked with a hawkish U.S.- and Australian-government sponsored think tank to purge nearly 200,000 Chinese, Russian and Iranian accounts from its platform. It has also worked hard to remove Venezuelan users critical of U.S. regime change, including large numbers of government members. Meanwhile, despite detailed academic work exposing them, Venezuelan opposition bot networks remain free to promote intervention.

Facebook has also been working hand-in-hand with the Atlantic Council, a NATO think tank, to determine what users and posts are legitimate and what is fake news, effectively giving control over what its 2.4 billion users see in their news feeds to the military organization. Reddit, another huge social media platform, recently appointed a former deputy director at the council to be its head of policy.

Earlier this year, Facebook announced that it was banning all positive appraisals of Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian general and statesman assassinated by the Trump administration. This, it explained, was because Trump had labeled the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) a terrorist organization. “We operate under U.S. sanctions laws, including those related to the U.S. government’s designation of the IRGC and its leadership,” it said in a statement. This is particularly worrying, as Soleimani was the country’s most popular public figure, with over 80 percent of Iranians holding a positive view of him, according to a University of Maryland poll. Therefore, because of the whims of the Trump administration, Facebook began suppressing a majority view shared by Iranians with other Iranians in Farsi across all its platforms, including Instagram. Thus, the line between the state, the military industrial complex, and big media platforms whose job should be to hold them to account has blurred beyond distinction. The incident also once again highlights that big tech monopolies are not public resources, but increasingly tightly controlled American enterprises working in conjunction with Washington.

More worryingly, it is the tech companies themselves who are pushing for this integration. “What Lockheed Martin was to the twentieth century,” wrote Google executives Eric Schmidt and Larry Cohen in their book, The New Digital Age, “technology and cyber-security companies [like Google] will be to the twenty-first.” The book was heartily endorsed by Atlantic Council director Henry Kissinger.

After an online outcry including journalists like Ben Norton directly appealing to administrators, the accounts were reinstated today. However, the weekend’s events are another point of reference in the trend of harassing and suppressing independent, alternative or foreign media that challenges the U.S. state power, an increasingly large part of which is linked to the big online media platforms we rely on for free exchange of ideas, opinions and discourse.

On the incident, MintPress founder Mnar Muhawesh said:

Twitter’s ban hammer and censorship army of flaggers is an attempt to re-tighten state and corporate control over the free flow of information. That’s why it’s no wonder independent media like MintPress News, Kawsachun, and watchdog journalists covering state crimes like Ollie Vargas have been targeted in what appears to be an organized effort to silence and censor dissent. Twitter’s message is very clear: our first amendment is not welcome, as long as it challenges establishment narratives.”

Alan MacLeod is a Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent.

Parliament summons Jeanine Áñez to clarify corruption scandal

By Lucas Leiroz | May 29, 2020

The coup d’état carried out in Bolivia was the starting point for a major wave of social, political and economic setbacks in the country. Bolivia is the poorest country in South America, with very high poverty rates, however, during the years of Evo Morales, the country’s growth was enormous, reaching the point of being the South American country with the greatest economic growth. The seizure of power by the coup d’état represented the return of the worst growth rates, in addition to a huge escalation of violence against indigenous populations – extremely respected previously by Evo Morales – and gigantic corruption scandals.

Bolivia’s interim president, Jeanine Añez, recently proved the nature behind the new government by being indicted in a lawsuit. Añez and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Karen Longaric, were the first people summoned to provide information for a current investigation. The charge against both is of involvement in corruption networks during the purchase of ventilators and other medical supplies to – supposedly – fight the pandemic.

The corruption scandal in Bolivia started a few weeks ago, when health professionals reported that the Spanish ventilators acquired by the Bolivian State were of low quality and unfit for hospital use with the purpose of facing a pandemic. According to official sources, the Bolivian government has spent more than $27,000 on each device (about 170 devices), while domestic producers (Bolivians) charge about $1,000.

“This investigation will summon Jeanine Áñez, Longaric and other officials involved in this purchase that has become theft of the pockets of the entire Bolivian people,” lawmaker Édgar Montaño told reporters. According to the parliamentarian, Áñez must acknowledge that she knew all the details of the agreement, which she herself had ordered, while Longaric must explain why no action was taken after the Bolivian consul in Barcelona sent a report with the details of the contract. It is also worth remembering that, on Wednesday (May 20), Bolivia’s Minister of Health, Marcelo Navajas, was arrested and dismissed from office on suspicion of involvement in the corruption scandal.

As investigations progress, the situation becomes increasingly serious for Bolivian domestic politics, as major corruption schemes and illicit deals are discovered, revealed, and meticulously used as political weapons in party disputes within the country. Some people and groups that support the legitimate Bolivian president, Evo Morales, are innocently celebrating the performance of the Bolivian Parliament “against the coup”, but, in fact, there is no reason to celebrate so far.

If, on the one hand, there is something positive in the fact that the illicit activities of the coup government are being exposed, on the other, the central objective of the coup is being accomplished: the intention of the groups that financed and supported the overthrow of Morales was never to put Jeanine Añez (or any other politician) in power, but to completely destabilize the Bolivian State, creating a scenario of absolute political chaos, with total institutional bankruptcy, thus facilitating the transformation of Bolivia into a land of foreign interference.

In fact, we can predict that from now on it is likely that the next presidents of Bolivia, be they left or right (terms absolutely outdated and geopolitically irrelevant), will fall in succession, without completing their mandates and the country’s command will remain, thus, vulnerable and without a central guardian of law and order. Within the chaotic scenario, the irregular action of external agents and foreign meddling in Bolivia will be simpler and, in addition to structural problems such as poverty and hunger, Bolivians would have to deal with a situation of total subordination to foreign powers – which it did not exist in the time of Morales, when the country tried to chart a sovereign and independent way, besides achieving diverse progress in many social indices.

What now happens in Bolivia can also be seen when we analyze several previous experiences. Countries victimized by the so-called “colorful revolutions” – hybrid wars disguised under the mask of democratic revolutions – tend to be characterized after the outcome of such “revolutions” by the establishment of true “zombie states”, which consist of nothing more than innocuous institutions and without any strength to deal with the real problems of their countries.

With the presidential election situation still uncertain in the midst of the pandemic – the Executive Branch and the Judiciary made different decisions and, amid institutional chaos, nothing is yet fully defined – the future of the Bolivian government is really unknown, but the scenario is very pessimistic, with few expectations of overcoming the crisis. The tendency is for Jeanine to fall and, after her, the next president will also not fulfill his mandate completely. In contemporary hybrid warfare, attacks are continuous and “colorful revolutions” tend to be permanent.

Lucas Leiroz is a research fellow in international law at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.