The Hidden Map: US and Israel May Use Unexpected Neighbors to Attack Iran

By Robert Inlakesh | The Palestine Chronicle | February 15, 2026

Amidst heightened tensions between the US-Israeli alliance and Iran, an enormous amount of focus has been placed in the media on Iran’s missile program and how this will impact any upcoming war. What is often ignored are the origins of the regional threats to Tehran and its stability.

While covering each and every threat to the Islamic Republic of Iran would be beyond the scope of such an article, there are a number of hostile nations surrounding the country that can be used to destabilize the nation. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) and, to a lesser extent, Azerbaijan, are often cited as pro-Israeli, but there is another nation that flies under the corporate media’s radar.

Iran shares its second-largest land border with the nation of Turkmenistan, a country that is rarely mentioned as a regional player. What many don’t know is that the nation, long characterized as a neutral player, has strong ties with both the US and Israel.

Turkmenistan: Neutral State or Strategic Corridor?

Unlike many Muslim-majority nations, Turkmenistan has long recognized and maintained ties with the Israelis, their relationship beginning in 1993. Then, in April of 2023, these ties were further cemented with the inauguration of a permanent Israeli embassy in Ashgabat for the first time.

It should therefore be no surprise that Tel Aviv and Ashbagat’s relationship is closest in the intelligence sharing and security cooperation spheres. Afterall, the Israeli embassy – opened back in 2023 – was strategically placed only 17 kilometers away from Iran’s border, marking a major symbolic achievement for Israel, especially as it operates through what are suspected to be thousands of Mossad recruited agents inside the Islamic Republic.

Although Israel has no official military bases inside Turkmenistan, there have been a number of reports indicating that it has set up attack drone bases inside the country. This would make sense, considering that Ashbagat has been purchasing Israeli drone technology since the 2010s, more recently acquiring the SkyStriker tactical loiter munition (suicide drone), developed by Elbit Systems.

Ashgabat has long been in alignment with the West. In May of 1994, it became the first country to join NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) program. However, the following year, the UN approved granting Turkmenistan the status of a neutral country, meaning it would not join military blocs.

In 2001, following the September 11 attacks, this neutral stance suddenly began to change. While other Central Asian nations – Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan – all immediately offered their military bases to the United States, due in large part to their concerns over the advancements of the Taliban, Turkmenistan only publicly admitted to allowing the US to use its airspace for military cargo aircraft to travel in transit.

In reality, the US airforce were operating a team on the ground in Ashgabat in order to coordinate refueling operations. In 2004, the Russian State protested the growing US-Turkmenistan military relationship, after reports emerged stating that American forces had “gained access to use almost all the military airfields of Turkmenistan, including the airport in Nebit-Dag near the Iranian border.”

Reports, which are not possible to independently verify but nonetheless have appeared consistent throughout the years, indicate that the US military has even established remote desert bases throughout different locations inside Turkmenistan.

Clinging to its neutral status on the public stage, Ashgabat rejects any mention of cooperation of this kind, including the denial of a 2015 statement by then US Central Command chief Lloyd Austin that the Turkmens had expressed their interest in acquiring US military equipment.

Signals of Military Activity

Perhaps the most concerning developments are the more recent revelations, revealed through OSINIT channels and Turkmen media, citing flight trackers to monitor the movement of US aircraft in the region. These reports indicate the confirmation that US Air Force transport aircraft C-17A Globemaster III and MC-130 Super Hercules have landed at undisclosed locations in Turkmenistan.

The significance of this, opposed to the rest of the military buildup that has been occurring in potential preparation for an attack on Iran, is that of the MC-130 Super Hercules, which is used specifically for transporting special forces teams, running night operations, as well as performing unconventional takeoffs and landings.

Paired with a recent report issued by the New York Times, indicating that the US’ options not only include an air campaign against Iranian nuclear and missile sites, but ground raids using special forces, it could be concluded that Turkmenistan is the location from which the US may seek to inject special forces units into Iran.

The Wider Ring around Iran

The Turkmenistan factor clearly cannot be ignored here, despite it often being dismissed as a neutral power that maintains friendly relations with both Russia and China. In fact, because of these relationships, with Moscow in particular, Tehran has refrained from attempting to expand its reach into the Central Asian country.

To Iran’s benefit is that Chinese and, to a lesser extent, Russian influence can reduce the extent to which the US and Israel can use Iran’s neighbors to threaten it. In Pakistan, for example, it is clear that both Islamabad’s joint security concerns – largely over Balochi militant groups – along its border, in addition to Beijing’s influence, make it highly unlikely that Pakistan would remain neutral and is instead inclined to help support Iran; within its limits, it should be added.

Azerbaijan is another potential threat to the stability of the Islamic Republic, due in large part to the large Azeri population in Iran’s own Azerbaijan Province. However, the vast majority of Azeri citizens are in fact loyal to the State and no major separatist movement exists at this time. The Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian and Ayatollah Khamenei himself are both ethnically part Azeri.

Meanwhile, many supporters of the Israeli puppet Reza Pahlavi openly express their intention to crack down on the Azeri ethnic minority inside Iran. During the reign of the CIA-MI6-installed Shah of Iran, minority groups suffered immensely, due to a clear tradition of ethno-nationalism that exists amongst the current supporters of the deposed monarchy.

Baku, for its part, is the top gas supplier to Israel, maintaining close military, diplomatic and intelligence ties with them. Azerbaijan even made Hebrew media headlines for its use of Israeli suicide drones and other military equipment during its war with Armenia.

On the other hand, Iran is militarily superior to Azerbaijan and has a considerable base of support amongst the nation’s population, of which the majority belong to the Shia branch of the Islamic faith. Therefore, Tehran has major leverage and could not only paralyze its oil and gas infrastructure, but perhaps has the potential of organic movements forming within Azerbaijan that will owe allegiance to Iran.

There is also the threat that the Israelis, in particular, will attempt to use Kurdish militant groups in Iraqi Kurdistan in order to carry out attacks on the Islamic Republic. Israel does not publicly acknowledge its presence in northern Iraq, yet Iran has directly struck its bases housing Mossad operatives in the past, while Kurdish separatist groups have been utilized countless times in attempts to destabilize the country. During the June 12-day-war last year, Israel also weaponized these proxies.

For those also concerned about Afghanistan’s role in threatening Iranian security, this has always historically been a precarious situation, yet Tehran has not only been improving its ties with Kabul, it officially recognized the Islamic Emirate during the past week. Again, this does not mean there is no potential threat there, but an alliance that holds with the Taliban government may prove important.

Gulf States, Jordan and the Regional Balance

Then there are the more obvious players, the UAE and Bahrain, which are not only partners of the Israelis as part of the so-called “Abraham Accords” but are overtly aligned with Tel Aviv’s regional agenda.

The Emiratis are speculated to hold some cards regarding trade, but their leverage is negligible. Both the Bahraini and Emirati leaderships are clearly anxious, because Iran’s responses to the use of their territory to attack the Islamic Republic could quickly collapse their regimes.

Jordan, meanwhile, is where the US appears to be focusing much of its military buildup, even withdrawing forces previously stationed in Syria’s al-Tanf region into the Hashemite Kingdom’s territory.

The Jordanian leadership is evidently permitting its territory to become a key battleground, which will likely be subjected to attacks if the US chooses to use it to aid the Israeli-US offensive, but it is simply powerless in such a scenario.

Jordan has become a Western-Israeli intelligence and military hub in the region, meaning that if King Abdullah II objects to the demands of its allies, he understands well that his rule could be ended in a matter of hours. Therefore, he must risk his country being caught in the crossfire and just hope that an internal uprising doesn’t take shape, which is one of the reasons why he has been so hostile to the Muslim Brotherhood, fearing they could end up leading any revolt as the organization did in Egypt.

Turkiye, on the other hand, which is also a major regional player, is likely to play both sides behind the scenes, attempting to stay out of such a fight. If it takes either side, it will suffer the repercussions. Perhaps the most important role it could play is to prevent its bases or airspace from being used by the US.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar both maintain cordial relations with Iran, clearly favoring a scenario where no war occurs at all, because they are home to US bases. As we saw last June, the US used its CENTCOM headquarters in Doha to direct its attack on Iran’s nuclear sites, and as a result, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) struck US facilities there.

Riyadh and Doha do not want to get dragged into such a scenario. It is also of note that they have a vested interest in neither side winning the war conclusively, because it is in their interests for there to be a multi-polar West Asia, not an Israeli-dominated region that will inevitably consume them.

A Conflict with Wider Consequences

Some have also speculated about Syria’s role in any war. Damascus is clearly in the US-Israeli sphere of influence, but it will have a negligible impact in its current form. If Syria’s military forces assault Lebanon or Iraq, they will suffer enormous blows and fail tremendously. The only wildcard with Syria is whether armed groups there will choose to use the opportunity to attack Israel, although as a military power, the Syrians are a relative non-factor at the current time.

For now, the US-Israeli plot to stir civil war inside Iran and to follow through with an air campaign that aids their proxies has failed. Given the readiness of Iran’s allies in Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, and even Palestine, perhaps beyond, the US would be entering a point of no return scenario if it were to attempt a regime change operation.

– Robert Inlakesh is a journalist, writer, and documentary filmmaker. He focuses on the Middle East, specializing in Palestine.

Why is the US using Jordan as the main base in possible Iran attack?

By Ali Jezzini | Al Mayadeen | January 23, 2026

US forces have amassed in Jordan ahead of a possible war on Iran, aiming to shift early retaliation away from Israelis, and exploit US airpower, while risking strategic miscalculation and overreach.

Over the past week, the United States has significantly reinforced its military footprint in West Asia amid rising tensions with Iran, deploying F-15 fighter jets and KC-135 tanker aircraft to Jordan’s Muwaffaq Salti Air Base as part of a broader repositioning of airpower ahead of a potential attack on Iran.

This buildup, which can be tracked using publicly available satellite images, comes against the backdrop of Iranian warnings to retaliate against American bases in the region should Washington — or its allies — launch an attack on Iranian territory. It also follows movements of US forces and dependents at several regional posts as a staging for possible offensive operations. The intensification of US deployments has thrust installations like Muwaffaq Salti, long a strategic node in Western forces’ deployment in West Asia, into the spotlight as both a potential launch point for attacks and a possible target in any wider conflict.

Why Jordan’s Muwaffaq Salti Air Base?

Part of the United States’ increasing focus on Jordan’s Muwaffaq Salti Air Base is not simply due to its distance from Iran’s most accurate short-range ballistic missiles, approximately 800–900 kilometers from Iran’s borders, but also because it may be intended to function as a primary Iranian target, or punching bag, in any initial phase of a wider war.

What follows is an attempt to analyze American strategic thinking, though it does not claim that events will necessarily unfold in this precise manner. From Washington’s perspective, “Israel” remains the crown jewel of the imperial order, an extension of US polity itself. During the most recent phase of confrontation, “Israel” encountered serious difficulties intercepting Iranian ballistic missiles, threats it now equates with nuclear weapons in strategic gravity. This urgency explains the current haste, as Iranians ought to possess much greater defensive capabilities in the future, coupled with the baptism by fire they endured during the June 12-day war.

Destroying Iran’s missile program outright is unrealistic, since large parts of the supply and production chains are dispersed in highly fortified underground facilities. As a result, targeting the Islamic system itself, seeking regime change, and sustaining what the US deems as acceptable costs may appear more logical to American planners. In their calculation, such an outcome would justify heavy losses, provided it ends the conflict definitively.

Israeli claims regarding the self-sufficiency and effectiveness of their air defenses are among the most exaggerated on earth. In reality, NATO intelligence and military capabilities played a decisive role in interception efforts, operating out of Jordan. This included US, Jordanian, and French air forces taking off from Jordanian bases, in addition to extensive intelligence, logistics, and aerial refueling missions done by NATO countries, including the UK.

Israeli leadership attempted to strike early under ideal surprise conditions before defensive gaps accumulated and before they were drawn into a prolonged escalation cycle they could not sustain. Even internal measures, such as preventing Israeli settlers from leaving during the war, reflected an acute awareness of how fragile the situation could become if panic spread; that kind of optics is strategically disastrous for a regime that sells itself as secure, resilient, and permanent.

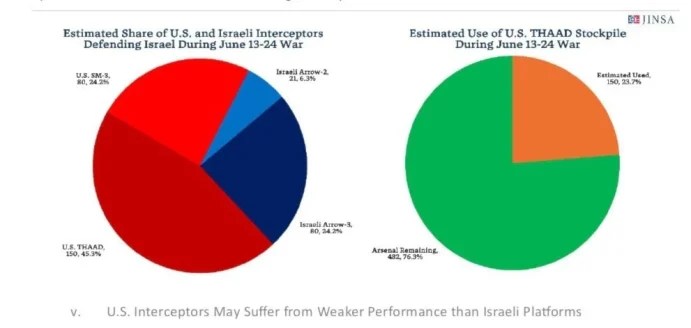

Most interception during the last confrontation in June 2025 was conducted by US naval assets using SM-3 interceptors and THAAD systems. Roughly 25 percent of all THAAD interceptors ever produced were reportedly consumed in that single episode. The persistent exaggeration of Israeli offensive and defensive capabilities, while significant but short-winded, serves two purposes:

- First, it counters the internal Israeli narrative that the United States “saved Israel” after October 7, a deeply sensitive issue tied to Israeli national security self-perception that panics at the idea of having such a level of dependency on the US.

- Second, it preserves an image of invincibility before regional actors, enhancing the regime’s deterrence.

Returning to Jordan: American planners show little concern for Jordanian costs or the consequences for the base itself, which is situated around 70km from the capital Amman. From this perspective, it may even be deemed acceptable for the US if Iran expends part of its ballistic arsenal striking the base, even at the cost of Jordanian casualties.

The American assumption is that they would then be able to launch a major air campaign to destroy Iranian missile production, storage, and launch sites. This would pave the way for an Israeli entry into a second phase of the war, one in which it would no longer face missile volumes it cannot absorb, as it almost did in the June war, as it was running out of interceptors after a presumed US airpower success in weakening the system and reducing launch capacity.

From Iran’s standpoint, directly starting with “Israel” may actually be more rational. An Israeli participation in any war appears almost inevitable, either immediately or at a later stage, for multiple reasons.

Despite the massive US buildup, which includes more than 36 F-15Es, an aircraft carrier, and several destroyers with capabilities to launch cruise missiles, Israelis still retain greater immediate regional firepower than the United States, but it seeks to avoid sudden, large-scale damage to its own infrastructure.

American intentions likely go beyond limited bombings, assassinations, or “decapitation” strikes, as seen previously, if their attack would make sense in terms of weighing gains and possible losses. They may include direct strikes targeting the Iranian leadership, severe economic and energy infrastructure degradation, and long-term destabilization designed to enable internal regime change, added to the sanctions.

The withdrawal of American aircraft from Gulf bases was not only due to their vulnerability to short-range, high-precision weapons that Iran’s arsenal is full of, but also to protect Gulf oil production in the event of war. Gulf states, for their part, would publicly distance themselves from hostilities to shield their economies and prevent market shocks, particularly to avoid upsetting Trump amid any market volatility.

While it is possible to disrupt US operations at Muwaffaq Salti Air Base, expending large numbers of ballistic missiles there, missiles that could instead strike high-value counter force and counter value Israeli targets, may be less strategically viable than other options if the US is prepared to escalate toward total confrontation regardless. Completely and permanently disabling the base would be difficult, and the strategic outcome would likely remain unchanged.

American planners appear convinced that Iran will avoid targeting Jordanian state infrastructure or attempting to destabilize the Jordanian monarchy, as such actions can be used for counterpropaganda. They assume Iran will focus on Western and Israeli forces, confining hostilities to sparsely populated desert areas that Jordan can absorb.

Jordan, governed by a monarchy heavily dependent on Western and Gulf countries’ political and economic support, appears to share this assessment. King Abdullah likely believes his rule faces no serious internal risk and that alignment with Western strategy is the safer course, as his country was credited for being “Israel’s” shield against Iranian drones in the June 2025 war.

Under this framework, the US would launch an air campaign using aircraft operating from Jordan to strike western Iran, while carrier-based aircraft in the Arabian Sea attempt to open corridors toward central Iran from the Gulf. This would allow heavy bombers from Diego Garcia to penetrate deeper and strike strategic targets. The Israeli occupation would then enter at a later stage.

The simplest counter-strategy is to do precisely what the Americans do not expect, and to inflict maximum cost. The theory that remains largely unrefuted: Trump is risk-averse. As Western media itself jokes, TACO (Trump Always Chickens Out), he dislikes long wars, favors last-minute, flashy interventions, and avoids sustained attrition. This suggests a vulnerability: American short-termism and reluctance to absorb prolonged pain, particularly when multiple theaters remain active.

Some may ask why Iran does not simply launch a preemptive strike. This is a clear option, but not an uncomplicated one. An initial Iranian strike could rally American public opinion behind a longer war, granting Trump broader authority, resources, and popular support. While it would disrupt US planning and cause early damage, it might ultimately strengthen Washington’s domestic position. By contrast, an American-initiated war, prolonged, unpopular, and costly, would be far more vulnerable to internal pressure, especially if American losses mount.

Adding to the complexity, two Emirati Il-76 cargo aircraft reportedly landed in Tel Aviv before flying on to Turkmenistan. These aircraft are known to be used by the UAE to supply proxy forces with weapons, particularly in Sudan and Somalia, raising the possibility that they were transporting drones or intelligence equipment for regional operations.

The picture remains highly complex, and it is entirely possible that nothing will happen. Still, based on current force deployments and escalation patterns, the probability of a US attack appears to have risen beyond a 50-50 threshold.

This analysis reflects what American planners may be thinking, not what will necessarily occur. It should be noted that after the previous war, many US and Israeli officials declared that Iran’s nuclear and missile programs had been torpedoed, and the system effectively destroyed, assessments that quickly proved false. Now, only months later, they appear to believe that an even more violent war is required to achieve what the last one supposedly already accomplished.

On the other hand, if endurance is possible and the United States is forced to retreat, Trump TACOs or abandon Israelis mid-conflict — an outcome not inconceivable under a president like Trump — the cumulative effects of “Israel’s” recent dominance and coercion across the region may yet be reversed.

As mentioned earlier, the US buildup is not sufficient to start a prolonged attack against Iran with the high goals of regime change. The buildup still does seem as defensive posturing shielding the Israelis, so a chance the Israelis might initiate and use the limited US and Western buildup as a shield is still significant. A scenario similar to what happened in the last war, but that does entail Israeli losses in the opening phase.

Conclusion

What emerges from this assessment is a US strategy built on supposed escalation control, risk displacement, and the assumption that others will behave within predefined limits. Washington appears to believe it can shape the battlefield geographically, pushing early phases of the war away from the fragile “Israel”, absorbing initial retaliation through peripheral bases, and then intervening decisively to reshape the balance before handing the fight back to Israelis under more favorable conditions. This is not a strategy aimed at victory in the classical sense, but at managing exposure and buying time.

The weakness in this thinking lies in its dependence on predictability. It assumes Iran will refrain from actions that collapse the carefully constructed sequencing of the war, that regional systems will remain stable under strain, and that American political leadership will tolerate the costs long enough to reach a decisive point. None of these assumptions is guaranteed. If any one of them fails, the entire escalation ladder becomes unstable.

Ultimately, the outcome of any confrontation will not be decided by the opening phase or by claims of technological superiority, but by endurance, political cohesion, and the ability to impose sustained costs on an adversary unwilling to absorb them.

The United States may possess overwhelming firepower, but it remains constrained by limited strategic patience and domestic vulnerability. If those constraints are effectively exploited, the very war designed to resolve the Iranian question may instead deepen American entanglement and erode the regional order it seeks to preserve.

The Taliban’s approach to the TAPI pipeline: challenges, and obstacles

By Farzad Bonesh – New Eastern Outlook – April 24, 2025

Although TAPI has now taken on more of a bilateral partnership between Afghanistan and Turkmenistan, its earlier implementation will certainly have greater domestic consequences for Afghanistan.

The Taliban’s approach to the TAPI pipeline: challenges, and obstacles

The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline, a combination of the first letters of the Latin names of the countries participating in the regional project, runs from Turkmenistan to India. The length of the 1,814-kilometer line is 214 kilometers in Turkmenistan and 816 kilometers in Afghanistan.

The TAPI project is intended to transport 33 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually from Turkmenistan’s The Galkynysh gas field to India.

In 2015, the leaders of the four TAPI participating countries celebrated the groundbreaking ceremony for the gas pipeline in the city of Merv. But apart from the laying of the Turkmen section, virtually no major activity took place.

After the Taliban returned to power, international financial institutions either refused to directly support the project due to legal and political considerations or showed no interest in investing.

The Afghan Taliban is not officially recognized, and international sanctions against the Taliban, political differences between India and Pakistan, and tense relations between Kabul and Islamabad have slowed down the implementation of the project.

However, in September 2024, former President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov and Taliban Prime Minister Mullah Mohammad Hassan Akhund jointly launched the TAPI project in 2024 at a ceremony on the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan border.

Recently, Hedayatullah Badri, Minister of Mines and Petroleum, and a high-ranking delegation from Turkmenistan, visited the progress of the TAPI gas transmission project in Herat province and emphasized the acceleration of the work process.

Although Pakistan and India have not been involved much in the recent developments of the TAPI gas pipeline, the Taliban, adopting a pragmatic approach, have decided to take this energy transmission project step by step with the cooperation of Turkmenistan.

Political and geopolitical goals and interests of the Afghan Taliban:

From the perspective of TAPI, it is an opportunity to solve the security problem within the country, and Kabul hopes that the opposition will also agree to the construction of this pipeline, considering national interests. During the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan , the Taliban, in a statement, while supporting the TAPI project, saw TAPI as an important economic project and an important element in the country’s economic infrastructure.

Gaining greater regional and global support for this pipeline will further link Afghanistan’s security with regional and global partners. The passage of the TAPI gas pipeline through Afghanistan will link the tangible and real interests of several regional and global countries, and the neighboring countries will also ensure Afghanistan’s security.

The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline project has helped increase Afghanistan’s geopolitical position and strengthen relations and mutual interests among partner countries. Taliban leaders seem to believe that TAPI has the potential to expand relations between member countries and strengthen common interests. Also, from the perspective of many in Kabul, the pipeline’s passage through Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India will reduce Pakistan’s incentive to play a negative role in Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, Kabul expects the TAPI project to encourage countries’ interests to move away from confrontation with each other in Afghanistan to a policy of tolerance.

In this approach, accurate and efficient management of the TAPI can have important effects on the public opinion of the people, show government efficiency, deal with the opposition, and satisfy nationalist feelings.

Economic goals and benefits:

Of course, this plan cannot pave the way for an economic revolution in Afghanistan, but it can be very useful for other major construction projects, reconstruction, economic development and production, trade, and transit in Afghanistan.

It will also employ about ten thousand people for the next few decades, creating thousands of direct and indirect jobs and reducing some of the unemployment problem.

Over the past few years, the Taliban have focused on several projects such as the TAP-500 energy system, the revival of important energy transmission and transit projects, including CASA-1000.

In addition, the Taliban have planned and inaugurated some infrastructure and economic projects, such as solar power generation over the past two years. The Taliban consider energy projects important in the development and self-sufficiency of the country, saving Afghanistan from poverty and dependence on expanding energy production, and managing water resources.

The implementation of TAPI can help transform Afghanistan’s energy consumption infrastructure from oil and coal to natural gas, and help increase the country’s production and economic growth.

For the first time, Afghanistan can achieve reliable natural gas for domestic and industrial use. For example, the TAPI pipeline passing through Herat province (the economic hub of Afghanistan) could be a driving force for other local industries.

Afghanistan could be an actor in a major transit route for Central Asia and a bridge between Central Asian energy-consuming and exporting countries. South Asian countries are in great need of energy, and Central Asian countries have abundant gas and electricity resources. Afghanistan has the potential to connect the two sides.

Success in this project could accelerate the construction of power transmission lines, railways, fiber optics, etc., in the field of regional cooperation. If TAPI is completed at a cost of more than $7-10 billion, it could also help attract foreign investment to the country. In addition to meeting the gas needs of its growing economy, Afghanistan could also receive $1 billion in gas transit rights annually. This amount could be a major contribution to the economy.

TAPI could be an important step towards strengthening the economic diplomacy of the Kabul government. Apart from the main role of Turkmen Gas Company, with an 85% stake, in July 2024, Pakistan and Turkmenistan agreed to accelerate the progress of the TAPI gas pipeline project.

Kazakhstan also seems to be willing to join the project. Russian companies may participate in the TAPI project, “as soon as the situation in Afghanistan stabilizes”.

Challenges and Outlook

TAPI suffers from major challenges, from insecurity to political complications, regional instability, the international isolation of the Taliban, and doubts about the investment capacity.

The TAPI project in the Turkmen section has been completed. The Taliban also plan four phases for construction from the Turkmenistan border to the city of Herat; Herat to Helmand; Helmand to Kandahar; and Kandahar to the Pakistani border. But as of April 2025, just 11 kilometers of pipeline have been laid in Afghanistan.

Large investments require security and stability, and major extremist groups such as ISIS can be a significant threat in Afghanistan.

The Afghan section of TAPI (in Herat, Farah, Nimroz, Helmand, and Kandahar provinces) passes through some of the most unstable parts of the country. The Taliban is not yet a legitimate government, with legal standing as an economic contracting party and a reliable partner. Critics have warned that the Taliban government does not have national legitimacy and international and legal recognition.

Pakistan and India appear to be cautiously refraining from immediately participating in the TAPI gas pipeline, waiting for conditions in Afghanistan to change.

While the Taliban has not been recognized yet, it is also not possible to secure financial assistance or loans from international institutions.

In addition, the full and successful construction and operation of the pipeline requires the political will of the leaders of the four countries and serious bilateral and multilateral discussions with all partners.

However, although TAPI has now taken on more of a bilateral partnership between Afghanistan and Turkmenistan, its earlier implementation will certainly have greater domestic consequences for Afghanistan.

Iran’s gas is the answer to world’s energy woes

Press TV – December 8, 2024

With the role of natural gas in future power generation being under debate by world countries amid a race to dramatically reduce carbon emissions, Iran is hosting a ministerial meeting of the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF).

Organizers say the meeting is an opportunity to exchange views among the member and observer countries as well as experts and specialists in the gas industry about the mechanism of consensus-building and strengthening communication and coordination on supply policies and related affairs.

While the future role of gas in the energy mix is the source of much contention among countries, the global gas consumption grew unprecedentedly in 2023, GECF Secretary General Mohamed Hamel told the forum’s opening in Tehran on Sunday.

He touched on the resilience of gas to regional conflicts and geopolitical strains which have exposed significant fragilties in the post-pandemic global energy system. Since the formation of the GECF in Tehran in 2001, global demand for natural gas has grown 70 percent, Hamel said.

The race to rapidly decarbonize and digitize the global economy under the net zero energy initiative has been subsumed by geopolitics that remains anchored in realist power struggles. The Ukraine war has undermined interdependence and prompted unprecedented levels of economic statecraft.

The need to rapidly move away from fossil fuels and fossil raw materials has exposed countries to a myriad of compliance risks with dire financial repercussions, leading to deepening instability, injustice and energy poverty.

Even the most optimistic clean energy projections indicate that by 2050, at least half of the world’s energy needs will still come from oil and gas resources. Hence, the rush to eliminate fossil fuels from the global energy system is unrealistic, threatening the world’s energy security.

According to the Energy Studies Institute of the International Energy Agency, gas will continue to play a significant role as a clean and cost-effective fuel in the global energy mix, accounting for 28 percent of the total by 2050. Forecasts indicate that by 2050, natural gas production and consumption will increase to more than 5.9 trillion cubic meters per year.

Asia-Pacific has emerged as the world’s largest net importer of natural gas. In 2023, China was the largest consumer of natural gas in the region, with around 405 billion cubic meters. Japan was the second-largest, with a consumption of around 92.4 billion cubic meters. The region’s gas consumption is forecast to hit 1.6 trillion cubic meters by 2050.

Also, predictions show that the largest share of the increase in natural gas production in the world will be from Russia, Iran, Qatar, and Turkmenistan.

Hence, the role of the Gas Exporting Countries Forum as a leading platform for dialogue and cooperation in order to provide a level of stability beneficial to both exporters and consumers and supporting the gas industry which requires significant effort and financing is of particular importance.

Iran, as the second largest holder of gas reserves in the world, has an important role to play in the gas diplomacy and guarantee its national interests and the interests of the other members.

The GECF countries hold 70% of the world’s proven gas reserves and produce some 40% of the world’s gas.

Despite years of sanctions, Iran has made significant progress in expanding its gas sector. The country now produces 275 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually, and gas accounts for more than 70 percent of its energy consumption.

Iran’s overall proven natural gas reserves excluding shale gas deposits and huge hydrocarbon reserves in the Sea of Oman and possibly the Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea are put at 34 trillion cubic meters, or about 17.8% of world’s total.

Assuming that the current unbridled consumption of about 250 billion cubic meters per year continues and with the pessimistic assumption that no new gas fields are discovered in the coming years, the existing supplies are enough to meet Iran’s needs for the next 130 years.

With investment and production from unconventional shale reserves which the country has already discovered, Iran’s gas supply capacity can rise more than twofold in the coming decade.

Exploratory research in the Sea of Oman has indicated the existence of gas hydrate reserves in Iranian waters in larger quantities than the huge South Pars field.

Further development of more than 20 fields currently producing gas can add another 500 million cubic meters a day to the country’s gas production capacity.

This huge capacity can be tapped to supply gas to the world markets through building new pipeline networks to neighboring countries and sending LNG to the rest of the world.

Afghanistan Forms Committee to Launch Practical Work on TAPI Gas Pipeline: Official

Samizdat – 20.08.2022

Afghanistan has established a committee to launch practical work on the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India Pipeline (TAPI) after a pause following the Taliban (under UN sanctions over terrorism) takeover, Esmatullah Burhan, a spokesman for the Afghan Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, said on Saturday.

“A ministerial committee has been formed. The Ministry of Finance carries out the financial affairs of this committee,” Burhan was quoted as saying by Afghan broadcaster TOLO News. The body will be headed by acting Afghan First Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Ghani Baradar, according to the report.

In addition, Afghanistan intends to send a delegation to Turkmenistan in the near future to discuss the implementation of the TAPI project, the broadcaster said, citing the foreign ministry.

“We will have a visit to Turkmenistan, and we will talk about the gas prices and implementation of projects in Herat and also the industrial parks,” Afghan foreign ministry spokesman Shafay Azam was quoted as saying.

In February 2021, the Taliban pledged not to jeopardize the TAPI project after a meeting of the movement’s delegation with Turkmen Foreign Minister Rashid Moradov. However, last year, the chaotic security situation in Afghanistan still hampered the pipeline’s construction.

TAPI’s construction was launched in 2015. The 1,814-kilometer (1,127 miles) pipeline will transport natural gas from Caspian Sea deposits in Turkmenistan via Afghanistan and Pakistan to India. The annual capacity of the pipeline is expected to reach 33 billion cubic meters (1.1 trillion cubic feet).

Tanzania – The second Covid coup?

By Kit Knightly | OffGuardian | March 12, 2021

John Magufuli, President of Tanzania, has disappeared. He’s not been seen in public for several weeks, and speculation is building as to where he might be.

The opposition has, at various times, accused the President of being hospitalised with “Covid19”, either in Kenya or India, although there remains no evidence this is the case.

To add some context, John Magufuli is one of the “Covid denier” heads of state from Africa.

He famously had his office submit five unlabelled samples for testing – goat, motor oil, papaya, quail and jackfruit – and when four came back positive and one “inconclusive”, he banned the testing kits and called for an investigation into their origin and manufacture.

In the past, he has also questioned the safety and efficacy of the supposed “covid vaccines”, and has not permitted their use in Tanzania.

In the Western press Magufuli has been portrayed as “anti-science” and “populist”, but it is not fair to suggest that the health of the people of Tanzania is a low priority for the President. In fact it’s quite the opposite.

After winning his first election in 2015 he slashed government salaries (including his own) in order to increase funding for hospitals and buying AIDs medication. In 2015 he cancelled the Independence Day celebrations and used the money to launch an anti-Cholera campaign. Healthcare has been one of his administration’s top priorities, and Tanzanian life expectancy has increased every year while he has been in office.

The negative coverage of President Magufuli is a very recent phenomenon. Early in his Presidency he even received glowing write-ups from the Western press and Soros-backed think tanks, praising his reforms and calling him an “example” to other African nations.

All that changed when he spoke out about Covid being hoax.

When he was re-elected in October 2020 the standard Western accusations of “voter suppression” and “electoral fraud” appeared in the Western press which had previously reported his approval rating as high as 96%.

And the anti-Magufuli campaign increased momentum in the new year, with Mike “we lied, we cheated, we stole” Pompeo initiating sanctions against Tanzanian government officials as one of his final acts as Secretary of State. The sanctions were notionally due to “electoral irregularities”, but the obvious reality is that it’s due to Tanzania’s refusal to toe the Covid line.

Just last month, The Guardian, always the tip of the spear when it comes to “progressive” regime change ran an article headlined:

“It’s time for Africa to rein in Tanzania’s anti-vaxxer president”

The article makes no mention of goats, papaya and motor oil testing positive for the coronavirus, but does ask – in a very non-partisan, journalistic way:

“What is wrong with President John Magufuli? Many people in and outside Tanzania are asking this question.”

Before going on to conclude:

“Magufuli [is] fuelling anti-vaxxers as the pandemic and its new variants continue to play out. He needs to be challenged openly and directly. To look on indifferently exposes millions of people in Tanzania and across Africa’s great lakes region – as well as communities across the world – to this deadly and devastating virus.”

The author doesn’t say exactly how Magufuli should be “challenged openly and directly”, but that’s not what these articles are for. They exist simply to paint the subject as a villain, and create a climate where “something must be done”. What that “something” is – and, indeed, whether or not it is legal – are none of the Guardian-reading public’s business, and most of them don’t really care.

Oh, by the by, the article is part of the Guardian’s “Global Development” section, which is sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Just so you know.

So, within two weeks of The Guardian publishing a Gates-sponsored article calling for something to be done about President Magufuli, he has disappeared, allegedly due to Covid. Funny how that works out.

Even if Magufuli miraculously survives his bout of “suspected Covid19”, the writing is on the wall for his political career. The Council on Foreign Relations published this article just yesterday, which goes to great lengths arguing that the President has lost all authority, and concludes:

“… a bold figure within the ruling party could capitalize on the current episode to begin to reverse course.”

It’s not hard to read the subtext there, if you can even call it “subtext” at all.

If we are about to see the sudden death and/or replacement of the President of Tanzania, he will not be the first African head of state to suffer such a fate in the age of Covid.

Last summer Pierre Nkurunziza, the President of Burundi, refused to play along with Covid and instructed the WHO delegation to leave his country… before dying suddenly of a “heart attack” or “suspected Covid19”. His successor immediately reversed every single one of his Covid policies, including inviting the WHO back to the country.

That was our first Covid coup, and it looks like Tanzania could well be next.

If I were the President of Turkmenistan or Belarus, I wouldn’t be making any longterm plans.

Is This The Most Important Geopolitical Deal Of 2018?

By Olgu Okumus | Oilprice.com | August 13, 2018

The two-decade-long dispute on the statute of the Caspian Sea, the world largest water reserve, came to an end last Sunday when five littoral states (Russia, Iran, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan) agreed to give it a special legal status – it is now neither a sea, nor a lake. Before the final agreement became public, the BBC wrote that all littoral states will have the freedom of access beyond their territorial waters, but natural resources will be divided up. Russia, for its part, has guaranteed a military presence in the entire basin and won’t accept any NATO forces in the Caspian.

Russian energy companies can explore the Caspian’s 50 billion barrels of oil and its 8.4 trillion cubic meters of natural gas reserves, Turkmenistan can finally start considering linking its gas to the Turkish-Azeri joint project TANAP through a trans-Caspian pipeline, while Iran has gained increased energy supplies for its largest cities in the north of the country (Tehran, Tabriz, and Mashhad) – however, Iran has also put itself under the shadow of Russian ships. This controversy makes one wonder to what degree U.S. sanctions made Iran vulnerable enough to accept what it has always avoided – and how much these U.S. sanctions actually served NATO’s interests.

If the seabed, rich in oil and gas, is divided this means more wealth and energy for the region. From 1970 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1991, the Caspian Sea was divided into subsectors for Azerbaijan, Russia, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan – all constituent republics of the USSR. The division was implemented on the basis of the internationally-accepted median line.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the new order required new regulations. The question was over whether the Caspian was a sea or a lake? If it was treated as a sea, then it would have to be covered by international maritime law, namely the United Nations Law of the Sea. But if it is defined as a lake, then it could be divided equally between all five countries. The so-called “lake or sea” dispute revolved over the sovereignty of states, but also touched on some key global issues – exploiting oil and gas reserves in the Caspian Basin, freedom of access, the right to build beyond territorial waters, access to fishing and (last but not least) managing maritime pollution.

The IEA concluded in World Energy Outlook (WEO) 2017 that offshore energy has a promising future. More than a quarter of today’s oil and gas supply is produced offshore, and integrated offshore thinking will extend this beyond traditional sources onwards to renewables and more. Caspian offshore hydrocarbon reserves are around 50 billion barrels of oil equivalent (equivalent to one third of Iraq’s total oil reserves) and 8.4 trillion cubic meters of gas (almost equivalent to the U.S.’ entire proven gas reserves). As if these quantities were not themselves enough to rebalance Eurasian energy demand equations, the agreement will also allow Turkmenistan to build the Trans-Caspian pipeline, connecting Turkmenistan’s resources to the Azeri-Turkish joint project TANAP, and onwards to Europe – this could easily become a counter-balance factor to the growing LNG business in Europe.

Even though we still don’t have firm and total details on the agreement, Iran seems to have gained much less than its neighbors, as it has shortest border on the Caspian. From an energy perspective, Iran would be a natural market for the Caspian basin’s oil and gas, as Iran’s major cities (Tehran, Tabriz, and Mashhad) are closer to the Caspian than they are to Iran’s major oil and gas fields. Purchasing energy from the Caspian would also allow Iran to export more of its own oil and gas, making the country a transit route from the Caspian basin to world markets. For instance, for Turkmenistan (who would like to sell gas to Pakistan) Iran provides a convenient geography. Iran could earn fees for swap arrangements or for providing a transit route and justify its trade with Turkey and Turkmenistan as the swap deal is allowed under the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA, or the D’Amato Act).

If the surface water will be in common usage, all littoral states will have access beyond their territorial waters. In practical terms, this represents an increasingly engaged Russian presence in the Basin. It also reduces any room for a NATO presence, as it seems to be understood that only the five littoral states will have a right to military presence in the Caspian. Considering the fact that Russia has already used its warships in the Caspian to launch missile attacks on targets within Syria, this increased Russian presence could potentially turn into a security threat for Iran.

Many questions can now be asked on what Tehran might have received in the swap but one piece of evidence for what might have pushed Iran into agreement in its vulnerable position in the face of increased U.S. sanctions. Given that the result of those sanctions seems to be Iran agreeing to a Caspian deal that allows Russia to place warships on its borders, remove NATO from the Caspian basin equation, and increase non-Western based energy supplies (themselves either directly or indirectly within Russia’s sphere of geopolitical influence) it makes one wonder whose interests those sanctions actually served?

Caspian Sea Convention Bans Military Presence of Non-Littoral States in Region

RT | August 12, 2018

Vladimir Putin attended the Caspian Sea summit in Kazakhstan which he said has “milestone” significance. There five littoral powers finally made a breakthrough on trade, security and environment following 20 years of talks.

This year’s meeting has been “an extraordinary, milestone event,” Russian President Vladimir Putin told his counterparts in Kazakhstan’s port city of Aktau, where the summit took place. Leaders of the Caspian Five came there to seal a convention on the legal status of the sea washing shores of Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan.

“It is crucial that the convention governs … maritime shipping and fishing, sets out military cooperation among [Caspian] nations and enshrines our states’ exclusive rights and responsibilities over the sea’s future,” Putin said. He added the landmark accord also limits military presence in the Caspian Sea to the five littoral countries.

From now on, no country from outside the region will be allowed to deploy troops or establish military bases on the Caspian shores. The five states themselves will also decide on how to deal with issues currently affecting the Caspian Sea region, such drugs and terrorism.

“Hotspots, including Middle East and Afghanistan, aren’t far away from the Caspian Sea,” the President stated. “Therefore, the very interests of our peoples require our close cooperation.”

The summit may give boost to digitalization of commerce, mutual trade and logistics, Putin suggested. “Transportation is one of key factors of sustainable growth and cooperation of our countries,” he argued. Additionally, the five states will establish the Caspian Economic Forum “to develop ties between our countries’ businesses,” Putin told.

The Caspian Sea is home to some 48 billion barrels of oil and 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in proven offshore reserves. A range of important pipelines are going through the Caspian Sea, connecting Central Asia and Caucasus with the Mediterranean.

US in Afghanistan to Influence Russia, Iran, China – Russian Foreign Ministry

Sputnik – March 14, 2108

The United States retains its presence in Afghanistan to exert influence on neighboring countries and regional rivals – namely, Russia, Iran and China, Russian Foreign Ministry’s Second Asian Department Director Zamir Kabulov told Sputnik in an interview.

“In our opinion, the United States is in Afghanistan primarily with the aim of controlling and influencing the political processes in its neighboring countries, and also demonstrating its power to its regional competitors, primarily China, Russia and Iran. The United States is clearly trying to achieve destabilization of Central Asia and later transfer it to Russia in order to subsequently present itself as the only defender against potential and emerging threats in the region,” Kabulov said.

According to the diplomat, Russia and other countries neighboring with Afghanistan have questions about the true goals and time frame of the US military presence in the Central Asian country.

“If the United States and its NATO allies intend to continue their destructive policy in Afghanistan, this will mean that the West is heading toward the revival of the Cold War era in this part of the world. We closely monitor the developments and are ready to respond in cooperation with our partners and other like-minded people,” Kabulov noted.

The diplomat pointed out that Washington still failed to understand that the Afghan conflict could not be resolved solely by military means, stressing that it was impossible to defeat the Taliban by force.

Moscow is puzzled by the attempts of the United States and NATO to persuade Afghanistan to replace Russian weapons and military equipment, such move leads to reduction of Afghan’s military potential, Zamir Kabulov told Sputnik in an interview.

“The course taken by the United States and NATO to persuade Kabul to replace Russia-made small arms and aircraft is surprising, as it will inevitably lead to a decrease in the combat capabilities of the Afghan armed forces and further deterioration of the situation,” Kabulov said.

The diplomat reminded that a bilateral intergovernmental agreement on Russia’s defense industry assistance to Afghanistan had entered into force in November 2016, adding that the document created the legal framework for Russian assistance in arming and equipping the Afghan security forces.

“At the moment, negotiations are underway on repairs and supplies of spare parts for the Afghan Air Force’s helicopters for various purposes, produced in Russia (the Soviet Union),” Kabulov added.

Afghanistan Parliamentary Election

The parliamentary election in Afghanistan is unlikely to take place in July in the current circumstances, Kabulov said.

“I do not think that the parliamentary elections in Afghanistan will be held in July this year as scheduled. The Taliban continue to control about half of the country’s territory, engage in hostilities, organize and carry out terrorist attacks in large cities, and, apparently, are not going to make compromises and reconciliation with the Afghan government,” Kabulov said.

Afghanistan’s Independent Election Commission (IEC) is also unlikely to accomplish all the necessary procedures before the date set for the vote, given that the commission has announced earlier that the registration of voters will complete only by early August, the diplomat noted.

Furthermore, disagreements between the presidential administration and its political opposition regarding the parameters of the upcoming elections still remain unresolved, the official noted.

“In my opinion, if elections are conducted in the current circumstances, their results will not improve the political situation in the country and confidence in the current government, will not force the armed opposition to cooperate with the government,” Kabulov added.

The diplomat also noted that the Daesh terror group posed a serious threat to holding the election.

“The Daesh jihadists pose a serious threat to the security of the conduct of elections, especially in the north and a number of eastern provinces of Afghanistan. Some polling stations in the provinces of Helmand, Uruzgan, Kunduz, Badakhshan, Faryab and Ghazni are the most problematic in terms of security, according to the IEC data. I think that, in fact, the list of problematic areas in terms of organization of voting is much longer,” Kabulov said.

Afghanistan Reconciliation Talks

Russia considers the so-called Moscow format of talks an optimal platform for the promotion of national reconciliation in Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov noted.

“Unfortunately, the existence of a large number of international formats on the Afghan issue has not significantly contributed to the involvement of the Taliban in peace negotiations. In this regard, we consider the Moscow format of consultations launched by us in early 2017 as the optimal platform for substantive negotiations to promote national reconciliation and establish a constructive dialogue between the government of Afghanistan and the Taliban movement,” Kabulov said.

Kabulov also noted that Moscow considered the format of talks in the Afghan capital as one approach toward achieving a collective solution to the problems surrounding Afghan settlement.

“A signal of international support for the resolution of the intra-Afghan conflict through political dialogue with the government of Afghanistan has been sent to the Taliban. The Taliban ignored the recent meeting of the ‘Kabul process’ in the Afghan capital, insisting on direct talks with the United States,” the diplomat added.

In February 2017, Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, India and Afghanistan came together in Moscow for talks to promote the national reconciliation process in Afghanistan through regional cooperation with Kabul in the leading role. Apart from the aforementioned states, the latest round in April gathered five Central Asian countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. The United States refused to take part in the meeting.

Afghanistan has long suffered political, social and security-related instability because of the simmering insurgency, including that of the Taliban, but also because of the actions of the Daesh terror group.

The United States has been in Afghanistan for almost 17 years following the 9/11 attacks. Before his election, Trump slammed sending US troops and resources to the Central Asian country.

‘Russia set to fund railway line between Iran, Azerbaijan’

Press TV – July 3, 2016

Russia is reportedly poised to finance a railway line connecting Iran with its northern neighbor Azerbaijan.

According to Tasnim news agency, head of the press service of Azerbaijan Railways OJSC Nadir Azmammadov, has said that Russian Railways OJSC has discussed the terms of its participation in the financing of the Rasht-Astara (Iran)-Astara (Azerbaijan) railway with the related parties in the Azeri capital, Baku.

The report said representatives of the railways of Azerbaijan, Iran and Russia attended the talks in which the Azeri side informed the partners about the projects and tasks ahead.

Baku believes the international transport corridor will improve Azerbaijan’s transit potential as well as its ties with the other two countries.

Participants in the talks reportedly signed a final protocol.

The trilateral railway project is aimed at connecting Northern Europe with Southeast Asia.

The railway line will initially transport five million tonnes of cargo when it is launched in the near future.

Last November, Iran and Russia signed an agreement worth 1.2 billion euros to electrify a train line, linking north-central Iran to the northeastern border with Turkmenistan.

The agreement signed between Russian Railways and the Islamic Republic of Iran Railways (RAI) envisages constructing power stations and overhead power lines along the Garmsar-Sari-Gorgan-Inche Burun route in Iran.

“The implementation of the contract will improve the capacity of passenger trains and raise transit to 8 million tonnes,” said RAI Managing Director Mohsen Poursaeed-Aqaei who signed the document.

The train line, among the first in Iran with a history of 80 years, extends to Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan and links the Central Asia to the Persian Gulf and beyond.

The project was also set to be financed by the Russian government and would be implemented in 36 months, which includes manufacturing all electric locomotives inside Iran, electrifying 495 kilometers of railway and building 32 stations and 95 tunnels.

Can Washington Get a New Military Base in Central Asia?

By Vladimir Odintsov – New Eastern Outlook – 30.09.2015

The special attention that the United States has been paying to Central Asia, while actively seeking ways to implement a strategy of global leadership in the region that is now fully recognized as the center of Eurasia, has been covered in numerous articles, including those published in NEO.

According to the geopolitical concept of the recognized American political scientist Zbigniew Brzezinski: Those who control Eurasia control the world. Therefore, Washington’s steps to strengthen American influence in the region in the long run are completely predictable. The pivotal role in this policy is played by the US military bases in the region and military cooperation ties. After all, according to the globalist logic of the White House, American influence in any region must be supported by the “adequate” military force. The 9/11 events in the US and the consequent anti-terrorist intervention in Afghanistan have become a pretext for a major military deployment of American and NATO troops in Central Asia.

By the way, the ongoing engagement of US troops in Afghanistan confirms the notion that the presence of US and NATO forces in this country has little to do with the “struggle for democracy”. The true purpose of the military intervention in Afghanistan was the creation of powerful military bases, as the geographical position of this country is pretty unique in terms of the strategic freedom it provides. From this area Washington can launch a massive attack against Russia’s Urals and Siberia, different facilities in Central Asia, Iran, Pakistan, India and China. For this reason from the very start of the US invasion of Afghanistan, Shindand and Bagram Air Bases were transformed into massive construction sites where a large number of surface and underground facilities being built.

It happens so that for Pentagon Central Asia serves as a base for applying pressure on Russia, China, Iran and the entire Eurasian continent, it also plays a pivotal role in the post-conflict settlement in Afghanistan, since it may form a joint military alliance under the banner of opposition to the Islamic state.

In an effort to strengthen its positions in Central Asia under the above mentioned pretext, the United States has sent invitations to join the anti-ISIL military coalition to both Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. To add some momentum to the matter the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Central Asia at the U.S. Department of State Daniel Rosenblum has recently visited Tashkent, while the commander of United States Central Command general John Lloyd James Austin III made a trip to Dushanbe. In the course of their visits American emissaries discussed the situation in Afghanistan, regional security, and the advantages of cooperation with the United States “in the fight against international extremism” with regional authorities. Of course, a particular emphasis was made on the “need” to stay away from integration with Russia.

It is clear that in dealing with Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan “messengers of Washington” tried to make active use of the fact that those states today are free from obligations of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, which is headed by Russia, and therefore they are free to pursue military cooperation with the US. Therefore, Washington and Tashkent signed a document that provides the latter with free shipments of military equipment in the next five years. American equipment, trucks, military vehicles for a total worth of 6.2 million dollars will be just granted to this Central Asian state. This year, the United States has handed over to Uzbekistan armored class M-ATV, as well as armored repair and recovery equipment to support them, 308 cars and 20 repairs trucks with a total cost of at least 150 million dollars.

In dealing with Uzbek authorities American envoys had to mind the fact that the country entered the international counter-terrorism coalition immediately after September 11, 2001, while establishing special relations with a number of Western countries. As a result, the territory of the Republic at the time was housing a US military base, while the German Air Force had the opportunity to use the airfield in Termez, near the border with Afghanistan. Cooperation with Germany has been prolonged recently for a couple more years, though Tashkent is stressing the fact that the airfield in Termez is not a foreign military base. There’s little wonder to this fact, since the presence of foreign military bases was prohibited by law in Uzbekistan after the Andijan events, therefore in 2005 at the request of the Uzbek authorities American soldiers had to pack and leave.

Uzbekistan, is seeking ways to retain non-aligned status, and has no plans to allow any foreign military bases on its territory, on top of that it remains reluctant to send Uzbek troops abroad. This was pretty much the answer that the President of Uzbekistan Islam Karimov has given to Washington’s offer to join a coalition against the Islamic state.

However, Washington’s attempts to strengthen its military and political influence in Central Asia are far from over. Such efforts will certainly continue, despite the apparent reluctance of regional players to burden themselves with military obligations to the United States. America has severely damaged its reputation, therefore nobody believes in its peacemaking aspirations anymore, since the wars it has been waging are only leading to the suffering and misery of the civilian population of the countries it invades.